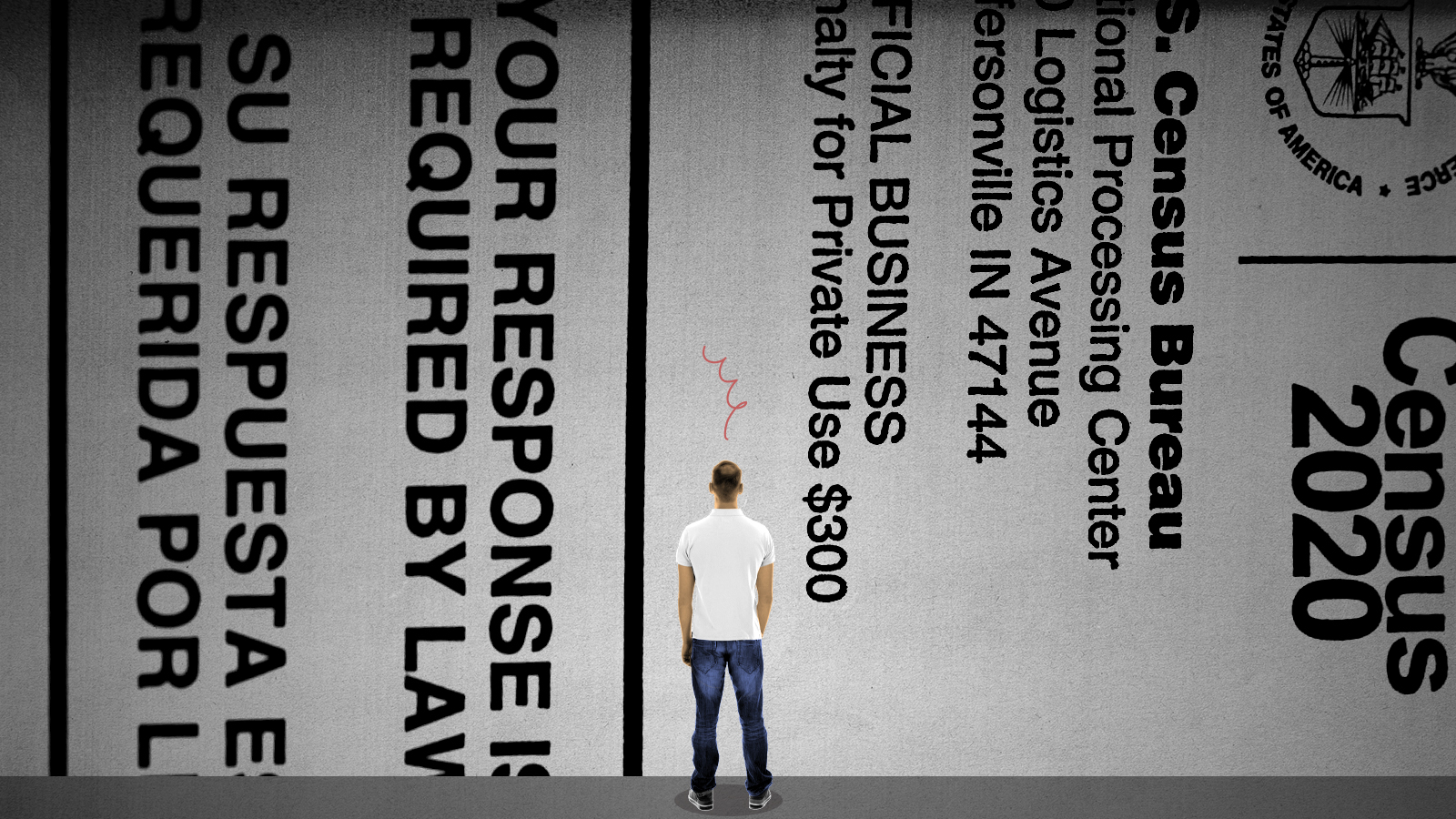

Should the census really ask about race and sexuality?

These questions undermine the survey's constitutional purpose

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

On Thursday the U.S. Census Bureau released the local level results of its decennial survey. Because these data are used to draw maps for the House of Representatives and state legislatures, the release marks the beginning of a months- or years-long struggle to secure partisan advantage.

Amidst the inevitable controversy, one quirk of this year's census may go unnoticed. That's the low response rate to questions about race, sex, and family relationships, even among households that reported their total number of residents. Missing data will complicate redistricting as well as efforts to better target public policy. But they send an important message: the classifications built into the census are crude, intrusive, and erode the principle of equality before the law.

Unanswered questions are nothing new. This time, though, the nonresponse rate apparently climbed from the historical average of under 3 percent to something between 10 and 20 percent. The gap may decline as the Census Bureau revises preliminary results. But it still poses a problem for figuring out who lives where.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

In order to supply missing data, census officials will employ a technique called imputation. For example, if a parent reported their own race, the census might assume the same about their children. In the 2002 case Utah v. Evans, a narrowly divided Supreme Court found that imputation does not violate the Constitutional requirement of "actual enumeration." Still, greater reliance on imputation is sure to provoke further litigation.

It's easy to see why political operatives, demographers, and lawyers worry about inaccurate numbers. From the citizen's perspective, though, there's something encouraging about refusal to complete a complicated eight-page form, to say nothing of supplemental surveys that further divide the population into bureaucratic categories.

Scholars call the aim of these sorting efforts "legibility." In his classic Seeing Like a State, the political scientist and anthropologist James C. Scott argued that legibility is among the central goals of the modern state. Before the 18th century, governments did not know very much about their populations. Systematic data collection was not just an attempt to improve understanding. The work of counting and classifying was a way of enhancing control.

The quest for legibility has an especially troubling history in the United States. From the very first census in 1790, the national government began sorting residents by race. Distinctions between whites, slaves, and "other free persons" were necessary to calculate representation under the "three-fifths" clause. In order to apply this clause, the government became responsible for generating quantified racial distinctions.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

It's tempting to think the census is merely collecting information that is already "out there." The concept of legibility suggests that the act of counting helps generate the reality it is supposed to document. Scholars Karen E. Fields and Barbara J. Fields dubbed this process "racecraft." Essentially, they argued that dividing the population into racial groups encouraged people to think of themselves as belonging to those same groups, which made the categories themselves seem essential.

The problem isn't limited to race. Last month, the Census Bureau announced it will collect information about sexual orientation and gender identity on the Household Pulse Survey it has administered during the pandemic. The stated intention is to better target relief to the people who need it. What it actually does, as with race, is to further reify categories and weave them into the fabric of public policy.

Such initiatives seem constitutionally permissible. In a series of cases going back to the 1870s, the Supreme Court found that Congress has the power to collect various kinds of data that go beyond a simple headcount. It's worth asking, though, whether collecting ever more elaborate and detailed demographic information is compatible with equality under the law. In principle, a liberal democratic state is supposed to "see" us as equal citizens, not as members of racial, sexual, or other groups.

Not everyone accepts that principle, of course. A central claim of critical race theory is that such colorblind neutrality is chimerical. Despite their reputation for radicalism, though, advocates of this idea are part of the essentially statist drive for legibility that goes back centuries. The collection of extensive statistical data filtered through complex categories is necessary for increasing the power of the state to prevent disparate outcomes.

Although Hispanics have an especially fraught relationship to census categories, it's unlikely that refusal to answer questions about such matters on the recent census were acts of intentional civil disobedience to racecraft. More Americans used an online form that made it easy to skip sections. The Trump administration's failed attempt to add a question about citizenship may have made immigrants wary of submitting information. And the census probably suffers from the low trust that afflicts other institutions and has made polling more difficult.

Even so, blank questions send a clear warning. The government should tread carefully when trying to make our ethnic identities, family structures, and other intimate matters legible to its purposes. Our system of proportional representation in the House of Representatives and state legislatures requires accurate counts of the population. This year's results suggest that going beyond that purpose undermines the census and makes it less useful for its mandatory goal.

Samuel Goldman is a national correspondent at TheWeek.com. He is also an associate professor of political science at George Washington University, where he is executive director of the John L. Loeb, Jr. Institute for Religious Freedom and director of the Politics & Values Program. He received his Ph.D. from Harvard and was a postdoctoral fellow in Religion, Ethics, & Politics at Princeton University. His books include God's Country: Christian Zionism in America (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2018) and After Nationalism (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2021). In addition to academic research, Goldman's writing has appeared in The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, and many other publications.

-

Democrats push for ICE accountability

Democrats push for ICE accountabilityFeature U.S. citizens shot and violently detained by immigration agents testify at Capitol Hill hearing

-

The price of sporting glory

The price of sporting gloryFeature The Milan-Cortina Winter Olympics kicked off this week. Will Italy regret playing host?

-

Fulton County: A dress rehearsal for election theft?

Fulton County: A dress rehearsal for election theft?Feature Director of National Intelligence Tulsi Gabbard is Trump's de facto ‘voter fraud’ czar

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred