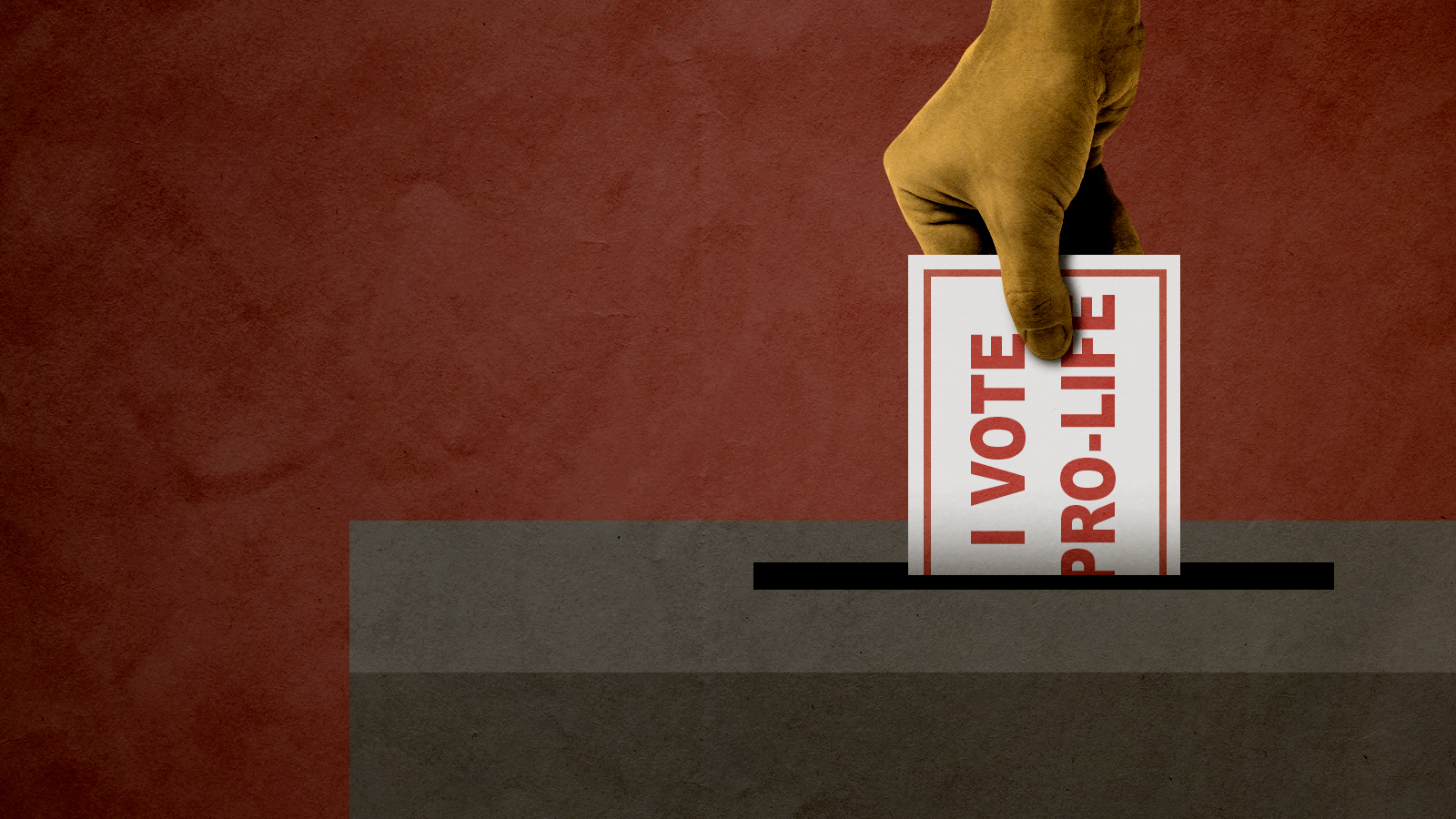

How far to the right can Republicans go?

Abortion bans are testing Americans' tolerance for far-right policies

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

As a political centrist who's voted exclusively for Democrats (or rather, against Republicans) for 18 years now, I've been making "popularist" arguments since long before the term was coined.

For those unfamiliar with it, "popularism" is the supremely commonsensical idea that Democrats should craft messages that appeal to the largest possible portion of the electorate and avoid staking out positions that are unpopular. In practical terms, this amounts to saying Democrats should lean into a broad-based economic message while soft-peddling support for polarizing cultural issues. The latter — examples include pushing to "defund the police," talking about the United States as a fundamentally racist country, and expressing blanket support for transgender women participating on female sports teams — are often advocated by progressive activists but poll badly.

As I said, it seems obvious that political parties seeking to maximize their margins of victory, and hence political power, in a democracy should do everything they can, within reason, to make themselves as popular as possible.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

But what about Republicans?

If Democrats risk losing elections by embracing unpopular positions, what's likely to happen to the Republican Party now that red states across the country have begun to pass stunningly radical bans on abortion when polls consistently show that something approaching six-in-10 Americans want abortion to be legal in all or most cases? Sure, the 39 percent who think the procedure should be illegal in all or most cases probably constitute a majority in many of these states. But then, plenty of blue states are more progressive than the median voter. This doesn't stop popularists from rightly fretting about its effect on the Democratic brand more broadly. Why don't Republicans worry about the same thing in ideological reverse?

There are ample reasons to think they should.

At some point between now and early July, the Supreme Court will hand down its decision in Dobbs v. Jackson Women's Health Organization, a case concerning a Mississippi law that bans abortion at 15 weeks, which is roughly eight weeks prior to viability of the fetus. Since Casey v. Planned Parenthood, the 1992 decision that affirmed Roe v. Wade (1973), viability has been treated as the line before which a ban on abortion is impermissible. If the high court allows the Mississippi law to stand, the viability line will cease to demarcate acceptable from unacceptable restrictions on abortion.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

What will replace it? It's too soon to say, but a series of Republican-dominated states have already passed trigger bans that will go into effect the moment the court overturns Roe and Casey or strikes their central rulings, moving the line much closer to, or nearly all the way back to, conception.

Other states have gone even further, passing six-week bans that have already gone into effect. Normally a court would quickly issue an injunction blocking enforcement of a law that directly transgresses a constitutional right until a court (and ultimately the Supreme Court) can weigh in on the matter. But Texas has devised a novel strategy for bypassing this procedure by empowering private citizens to enforce the law through the filing of lawsuits against anyone seeking to violate it (or against anyone aiding and abetting them in doing so).

This approach to enforcement, which critics have aptly dubbed a "bounty hunter" provision, has given Texas the ability to deprive potential plaintiffs of the ability to seek judicial relief. After all, the state and its agents (police officers, prosecutors, courts) aren't directly enforcing the law; individual citizens are, through the threat of monetary damages. Earlier this month, the Supreme Court clarified that this gambit has worked: No one has standing to seek relief from the law if it isn't being enforced by the state.

Already several states have passed, or are considering, laws with similar provisions. In Missouri, for example, a prominent antiabortion lawmaker has proposed a provision to the state's highly restrictive abortion law that would allow lawsuits against anyone crossing state lines (or helping someone do so) to procure an abortion. If enacted, this would infringe the freedom of interstate travel and effectively gut the jurisprudence of federalism, which denies the legitimacy of extraterritorial criminal law. (Only federal law can apply beyond the bounds of a single state.)

Another six-week ban, just signed into law by Idaho's Republican governor, empowers families of rapists to sue abortion providers when they facilitate the abortion of a "preborn baby" carried by the rape victim. Yet another, in Oklahoma, would use the Texas mechanism to ban all abortions 30 days after a pregnant woman's last menstrual period, effectively outlawing all abortion except in cases where ending the pregnancy would save the pregnant woman's life.

Will the GOP experience any electoral blowback nationally in response to these laws, which sound like something straight out of a totalitarian misogynistic dystopia? I would certainly hope so. Though there appears to be little sign of concern about it within the national party.

When Democrats talk about possibly trying some unorthodox and arguably foolish progressive approach to policy, liberal pollsters and strategists lapse immediately into panic mode — and for very good reason. But Republicans? They appear to be governed by the principle that there are and can be no negative electoral consequences from moving too far to the antiliberal right on cultural issues.

Are they correct about that? I certainly hope not. But if they are, that would raise some pretty troubling possibilities for every American with more liberal views.

For one thing, it would imply that those polls showing roughly 60 percent support for the pro-choice position are either flat wrong or failing to register how little the issue matters to many of those nominal supporters of abortion rights.

For another, and more broadly, it would seem to suggest that the American electorate as a whole is far more culturally conservative than Democrats have tended to assume in recent years. How that default conservatism can be squared with polls showing dramatic shifts in favor of same-sex marriage and away from regular churchgoing and religious affiliation over the past couple of decades is mysterious. Though it could be an expression, once again, of the lack of salience (or intensity) in the liberal direction on core cultural issues. That is, people might answer in the affirmative when a pollster asks if they support this or that liberal position on a cultural issue, but otherwise, they almost never think or care about it — including when red states pass laws that move sharply in the opposite direction in response to passionate lobbying by right-wing activists.

Whatever the case, a country in which the center-left party must hew closely to the center in order to win, but the center-right party isn't penalized for lurching ever further to the right, is not a country especially hospitable to liberal politics. One might even call it a country predisposed toward a harshly cruel form of conservatism.

Damon Linker is a senior correspondent at TheWeek.com. He is also a former contributing editor at The New Republic and the author of The Theocons and The Religious Test.

-

Why is the Trump administration talking about ‘Western civilization’?

Why is the Trump administration talking about ‘Western civilization’?Talking Points Rubio says Europe, US bonded by religion and ancestry

-

Quentin Deranque: a student’s death energizes the French far right

Quentin Deranque: a student’s death energizes the French far rightIN THE SPOTLIGHT Reactions to the violent killing of an ultraconservative activist offer a glimpse at the culture wars roiling France ahead of next year’s elections

-

Secured vs. unsecured loans: how do they differ and which is better?

Secured vs. unsecured loans: how do they differ and which is better?the explainer They are distinguished by the level of risk and the inclusion of collateral

-

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?IN THE SPOTLIGHT As the president muses about polling place deployments and a centralized electoral system aimed at one-party control, lawmakers are taking this administration at its word

-

House votes to end Trump’s Canada tariffs

House votes to end Trump’s Canada tariffsSpeed Read Six Republicans joined with Democrats to repeal the president’s tariffs

-

How are Democrats trying to reform ICE?

How are Democrats trying to reform ICE?Today’s Big Question Democratic leadership has put forth several demands for the agency

-

Is Alex Pretti shooting a turning point for Trump?

Is Alex Pretti shooting a turning point for Trump?Today’s Big Question Death of nurse at the hands of Ice officers could be ‘crucial’ moment for America

-

Halligan quits US attorney role amid court pressure

Halligan quits US attorney role amid court pressureSpeed Read Halligan’s position had already been considered vacant by at least one judge

-

House approves ACA credits in rebuke to GOP leaders

House approves ACA credits in rebuke to GOP leadersSpeed Read Seventeen GOP lawmakers joined all Democrats in the vote

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Vance’s ‘next move will reveal whether the conservative movement can move past Trump’

Vance’s ‘next move will reveal whether the conservative movement can move past Trump’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day