Germany's far-right Reichsbürger movement

Authorities say the conspiracy theorist and anti-semitic group – once dismissed as cranks – are of increasing concern

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The first of three trials linked to a far-right plot to overthrow the German government began in Germany this week, as the country grapples with the growing threat of far-right violence.

The suspects, part of the so-called "Reichsbürger" movement – which translates as "Citizens of the Reich" – were arrested in December 2022 after police uncovered a suspected plot to overthrow the German government.

Nine suspects believed to be part of the military arm of the far-right went on trial in Stuttgart on Monday, in the first of three "marathon" hearings which will see 27 people put on trial for their involvement in the alleged plot, said The Independent.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Another trial is set for 21 May in Frankfurt, against the 10 alleged ringleaders of the plot. A third will begin in Munich on 18 June against eight further suspected members.

Who was involved in the plot and what did they plan to do?

The alleged ringleader of the far-right plot is Heinrich XIII Prince Reuss, a 72-year-old estate agent supposedly descended from minor aristocracy. Had the coup been successful, he would allegedly have been made Germany's chancellor .

Other high-profile conspirators include Birgit Malsack-Winkemann, a judge and former representative of the far-right Alternative for Germany (AfD) in the Bundestag, who was allegedly to become the Justice minister.

The group is accused of planning to violently storm the German parliament and detain prominent politicians, including Chancellor Olaf Scholz, Foreign Minister Annalena Baerbock and conservative opposition leader Friedrich Merz.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

According to investigators, Reuss's group believed Germany was run by members of a "deep state" and that the country "could be liberated with the help of a secret international alliance", said France 24.

What is the 'Reichsbürger' movement?

The Reichsbürger are a movement of German conspiracy theorists and neo-Nazis who reject the legitimacy of Germany's post-Second World War Federal Republic.

First arising in the 1980s, it is a relatively "disparate" movement made up of organised groups and individuals across Germany, who hold varying degrees of resistance to the state, said Deutsche Welle (DW).

Although they are associated with the far-right, with many idolising Nazi Germany, Reichsbürger are known for subscribing to four conspiracy theories in particular: the belief that the pre-war German Reich is still a legitimate state; that the post-war Federal Republic of Germany does not have a valid constitution; that the Federal Republic is not a state at all but a private company; and that Germany is still under occupation by the Allies.

Reichsbürger are notorious for refusing to pay fines and taxes, ignoring court orders and declaring their own mini-states or territories. Examples include the "Exile Government of the German Reich" or the "Free State of Prussia", with members issuing their own passports, driving licences and currency.

Most members of the movement are men over 40, although some observers believe that there is a bigger female proportion of Reichsbürger than in the far-right extremist scene at large.

How many are there?

The movement was long estimated to be only in the hundreds for decades, but it has grown exponentially along with the rise of the internet, said France24, particularly in the last few years.

The movement was "increasingly radicalised" during the Covid-19 pandemic, with their beliefs gaining support from the so-called "Querdenker" movement, which refused to adhere to pandemic restrictions imposed by the government, added DW.

German intelligence agencies believe the movement could comprise as many as 20,000 people, of which it describes some 2,300 as "prepared to use violence", said DW.

How much of a threat do they pose?

Although long dismissed as "harmless cranks", in recent years they have been viewed as a growing security threat, said DW.

The group was officially placed under observation by Germany's domestic intelligence agency in 2016 after a Reichsbürger named Wolfgang P. shot and killed a Bavarian state police officer and shot at three others during an attempted confiscation of his cache of more than 30 firearms.

Authorities tracking extremist groups in Germany say they have recorded "a steady increase in crimes" from Reichsbürger since 2019, and revoked several thousand firearm permits.

But the potential threat the group posed "became most spectacularly apparent" in December 2022, when police raids uncovered the plot by Reuss and his co-conspirators to violently overthrow the German government and install an interim government to negotiate a new state order in Germany with the Allied powers of the Second World War.

Prosecutors say that Reuss's group had amassed up to €500,000 in cash, 380 guns, 350 bladed weapons, and around 148,000 rounds of ammunition.

The trial is expected to continue until January 2025, but due to the case's complexity, it could run for several years.

Sorcha Bradley is a writer at The Week and a regular on “The Week Unwrapped” podcast. She worked at The Week magazine for a year and a half before taking up her current role with the digital team, where she mostly covers UK current affairs and politics. Before joining The Week, Sorcha worked at slow-news start-up Tortoise Media. She has also written for Sky News, The Sunday Times, the London Evening Standard and Grazia magazine, among other publications. She has a master’s in newspaper journalism from City, University of London, where she specialised in political journalism.

-

Political cartoons for February 3

Political cartoons for February 3Cartoons Tuesday’s political cartoons include empty seats, the worst of the worst of bunnies, and more

-

Trump’s Kennedy Center closure plan draws ire

Trump’s Kennedy Center closure plan draws ireSpeed Read Trump said he will close the center for two years for ‘renovations’

-

Trump's ‘weaponization czar’ demoted at DOJ

Trump's ‘weaponization czar’ demoted at DOJSpeed Read Ed Martin lost his title as assistant attorney general

-

Who is paying for Europe’s €90bn Ukraine loan?

Who is paying for Europe’s €90bn Ukraine loan?Today’s Big Question Kyiv secures crucial funding but the EU ‘blinked’ at the chance to strike a bold blow against Russia

-

Pipe bombs: The end of a conspiracy theory?

Pipe bombs: The end of a conspiracy theory?Feature Despite Bongino and Bondi’s attempt at truth-telling, the MAGAverse is still convinced the Deep State is responsible

-

ECHR: is Europe about to break with convention?

ECHR: is Europe about to break with convention?Today's Big Question European leaders to look at updating the 75-year-old treaty to help tackle the continent’s migrant wave

-

X’s location update exposes international troll industry

X’s location update exposes international troll industryIn the Spotlight Social media platform’s new transparency feature reveals ‘scope and geographical breadth’ of accounts spreading misinformation

-

Revisionism and division: Franco’s legacy five decades on

Revisionism and division: Franco’s legacy five decades onIn The Spotlight Events to mark 50 years since Franco’s death designed to break young people’s growing fascination with the Spanish dictator

-

The party bringing Trump-style populism to Japan

The party bringing Trump-style populism to JapanUnder The Radar Far-right party is ‘shattering’ the belief that Japan is ‘immune’ to populism’

-

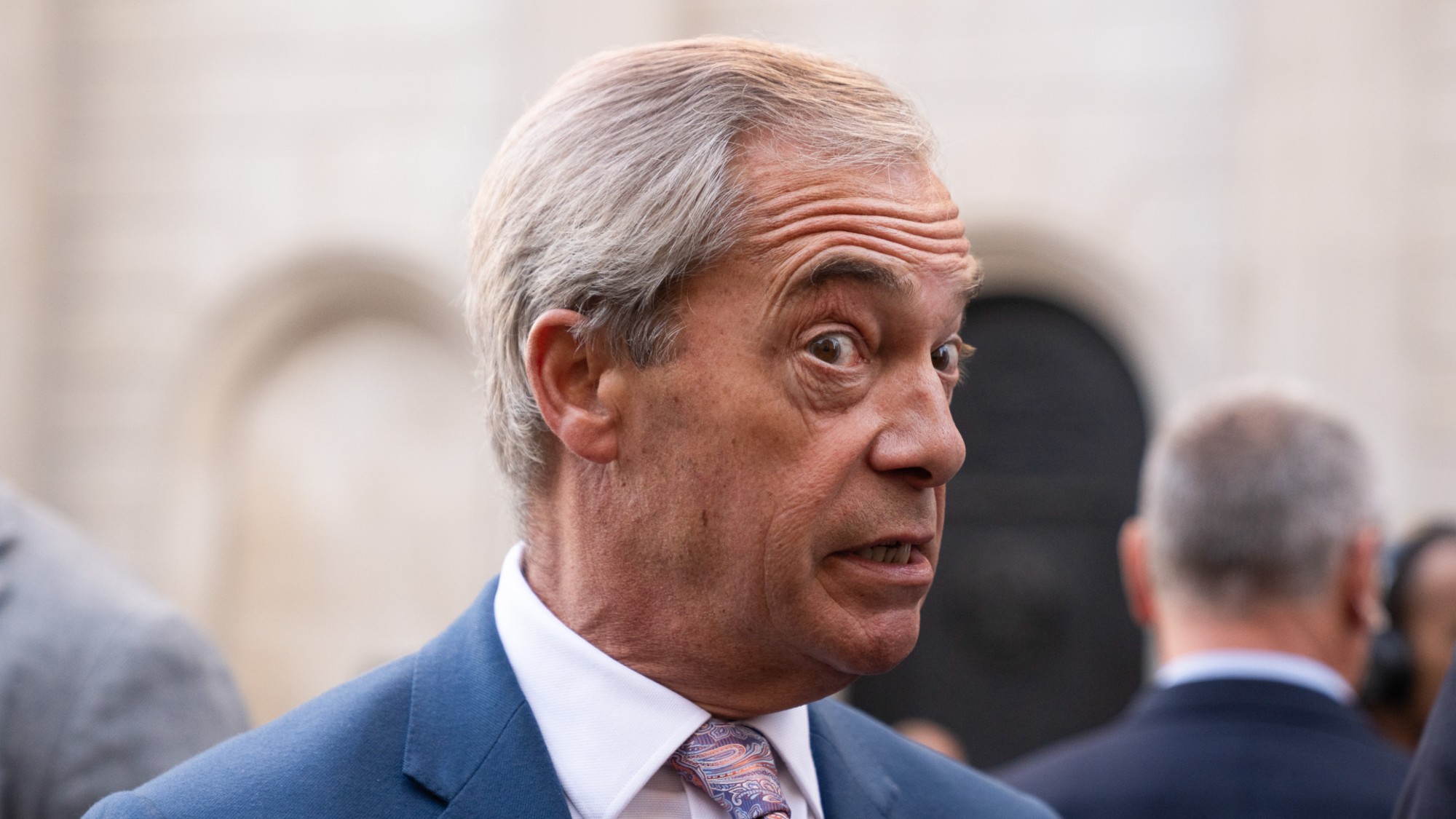

Does Reform have a Russia problem?

Does Reform have a Russia problem?Talking Point Nigel Farage is ‘in bed with Putin’, claims Rachel Reeves, after party’s former leader in Wales pleaded guilty to taking bribes from the Kremlin

-

‘Conspiracy theories about her disappearance do a disservice’

‘Conspiracy theories about her disappearance do a disservice’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day