The Supreme Court could rein in the SEC — and federal agencies as a whole

The court is hearing arguments on the agency's ability to enforce financial penalties

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The U.S. Supreme Court is set to hear a number of cases this term that could limit the power of the federal government. One of these cases is slated to come to a head on Wednesday, where the high court will hear oral arguments in SEC v. Jarkesy.

The case pits hedge fund manager George R. Jarkesy against the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), the agency responsible for regulating Wall Street and the nation's financial markets. Following an administrative investigation by the SEC, the agency's in-house judges found that Jarkesy had committed securities fraud, resulting in his being fined and barred from the financial sector. These in-house judges work for federal agencies as opposed to a judiciary, and adjudicate internal matters for these agencies.

Jarkesy sued the SEC, arguing that its use of in-house judges violated his right to a jury trial. "It is widely recognized that the SEC virtually always wins in its own home courts," Jarkesy's lawyers wrote in the case filing. If the Supreme Court rules in favor of Jarkesy, it could strip the SEC of its ability to levy fines while also minimizing the effectiveness of in-house judges and adjudicators across the federal government. Those in favor of small government have backed Jarkesy's lawsuit, while others have cautioned against further hindering federal agencies.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The case could 'destroy the government'

SEC v. Jarkesy "poses the most direct challenge yet to the legitimacy of the modern federal government," Noah Rosenblum wrote for The Atlantic. Jarkesy's main argument is that the SEC's in-house judges do not have the constitutional right to enforce laws. In the modern Supreme Court, this case has "a good chance of destroying the federal government's administrative capacity — taking down its ability to protect Americans' health and safety while unleashing fraud in the financial markets."

While these types of arguments "have been rejected by federal courts many times already," Rosenblum added, "the federal judiciary has drastically changed in recent years, and the Supreme Court with it — opening the possibility of a new, friendly reception to these absurd legal claims." Given that the SEC is the basic regulator of the financial markets, "the consequences of Jarkesy's success would be disastrous, especially for the American economy," Rosenblum said.

There are around 2,000 in-house judges working throughout the executive branch, and minimizing their power "could pose an existential threat to federal agencies that protect Americans and make determinations on the government benefits they are owed," Devon Ombres opined for the liberal think tank American Progress. If Jarkesy wins the case, it would show that the Supreme Court "is seeking to limit Congress' powers and put its policy preferences above those of elected officials."

The case could "create chaos for the millions of Americans and businesses who rely on the professionalism, consistency, and neutrality" of in-house judges to adjudicate issues, Ombres wrote. A ruling favorable to Jarkesy would also "overturn long-standing Supreme Court precedent that Congress has broad powers to delegate authority," he added.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

A jury trial is a 'bedrock constitutional principle'

The case puts at stake "a bedrock constitutional principle that colonists fought to defend in the American Revolution: the right to a trial by jury," opined the editorial board of The Wall Street Journal. Congress has granted the SEC — and other agencies — more power to levy penalties in recent years, and "Democrats wanted to make it easier for the agency to punish misconduct," the board added.

In-house trials "let SEC prosecutors present hearsay evidence and unauthenticated documents that would be inadmissible in a traditional federal court," the board said. So it is "no surprise, then, that the SEC wins almost all cases it charges in-house." The outlet added that these in-house courts "resemble those that the British government used to punish colonists."

Overreach "is precisely the kind of thing that is bound to happen when employees of a single administrative agency serve as prosecutor, judge and jury," Robert Johnson wrote for The Hill. "Independent judges and juries are supposed to stand between private citizens and the government. Agency bureaucrats are no substitute."

The consequences of ruling against the SEC "are not nearly as sweeping as the government suggests," Johnson opined. While the majority of in-house judges don't decide overly consequential cases, "when the government tries to take your money because it claims you did something wrong, then you are entitled to make your defense in a real court."

Justin Klawans has worked as a staff writer at The Week since 2022. He began his career covering local news before joining Newsweek as a breaking news reporter, where he wrote about politics, national and global affairs, business, crime, sports, film, television and other news. Justin has also freelanced for outlets including Collider and United Press International.

-

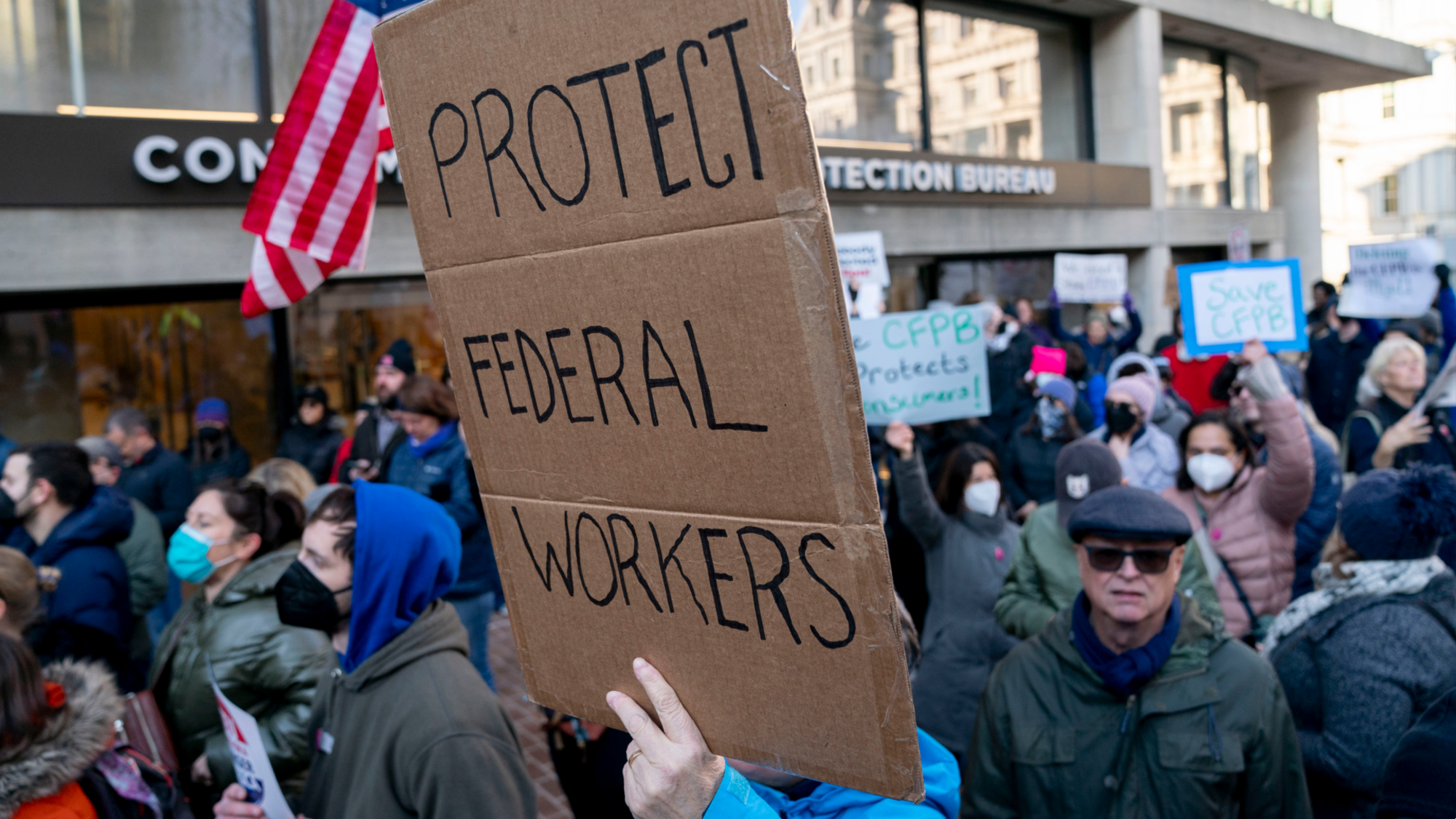

Trump reclassifies 50,000 federal jobs to ease firings

Trump reclassifies 50,000 federal jobs to ease firingsSpeed Read The rule strips longstanding job protections from federal workers

-

Supreme Court upholds California gerrymander

Supreme Court upholds California gerrymanderSpeed Read The emergency docket order had no dissents from the court

-

Gavin Newsom and Dr. Oz feud over fraud allegations

Gavin Newsom and Dr. Oz feud over fraud allegationsIn the Spotlight Newsom called Oz’s behavior ‘baseless and racist’

-

A running list of the US government figures Donald Trump has pardoned

A running list of the US government figures Donald Trump has pardonedin depth Clearing the slate for his favorite elected officials

-

How robust is the rule of law in the US?

How robust is the rule of law in the US?TODAY’S BIG QUESTION John Roberts says the Constitution is ‘unshaken,’ but tensions loom at the Supreme Court

-

‘These attacks rely on a political repurposing’

‘These attacks rely on a political repurposing’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

A crowded field of Democrats is filling up the California governor’s race

A crowded field of Democrats is filling up the California governor’s raceIn the Spotlight Over a dozen Democrats have declared their candidacy

-

The ‘Kavanaugh stop’

The ‘Kavanaugh stop’Feature Activists say a Supreme Court ruling has given federal agents a green light to racially profile Latinos