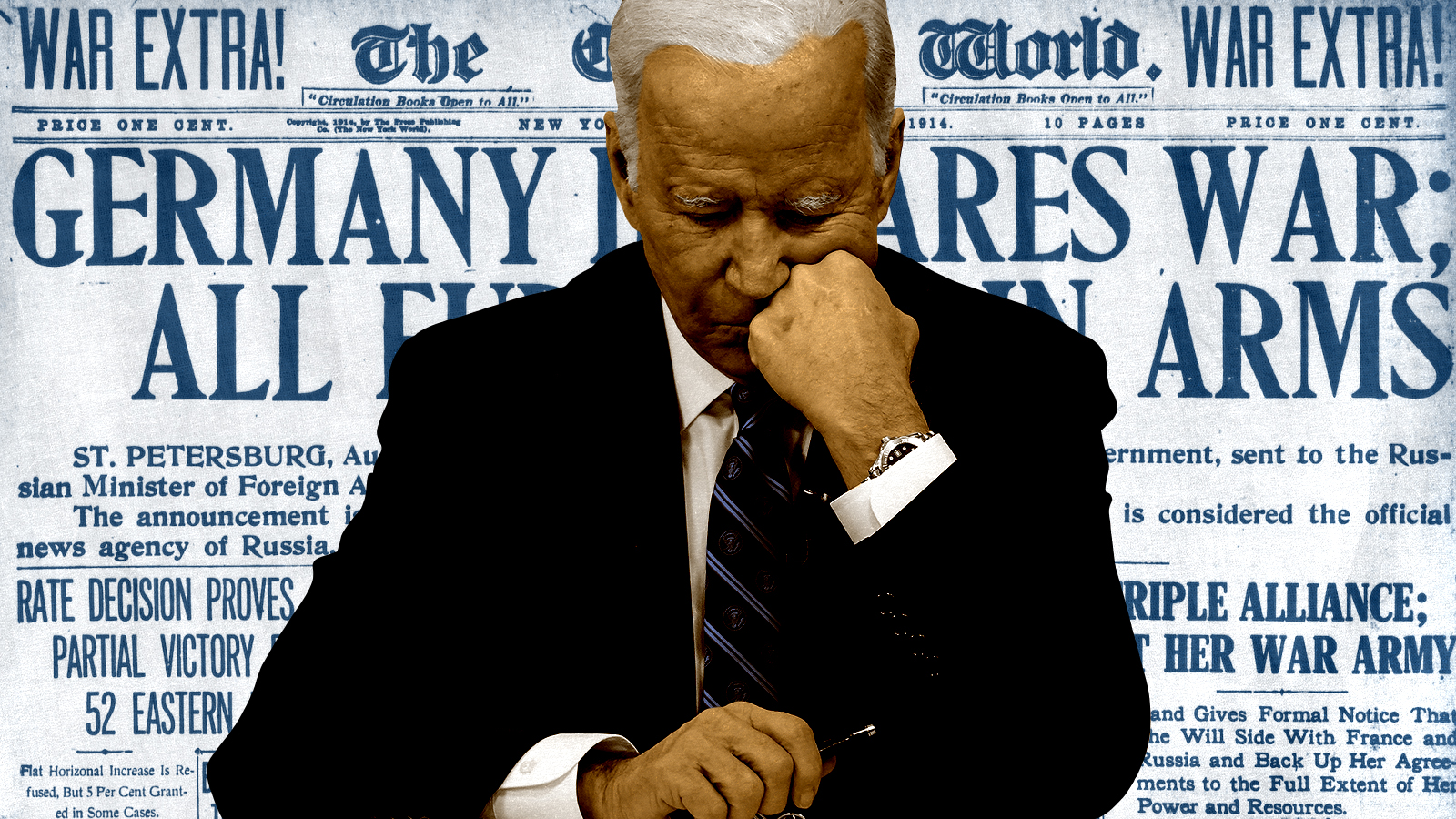

Why war in Ukraine could become America's fight

Can the U.S. avoid getting involved? History would suggest otherwise.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Every major war in Europe since 1914 has involved an initially reluctant United States: World War I; World War II; the Cold War; the Bosnian War. As Russia invades Ukraine and men, women, and children die, we have to ask the question: Can America avoid the fight?

The U.S. is always late for the party: appearing in the final months of the first World War after much of the carnage was done. Sitting out WWII for more than two years before being drawn in by an attack on the homeland by the Japanese. And again in Bosnia in the 1990s, when the U.S. led airstrikes against the Serbs after they slaughtered more than 8,000 Bosnian Muslim men and boys at Srebrenica.

There's an argument to be made that both WWI and Bosnia were wars of choice, from an American perspective. Not so much with the other two.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Before WWI, the U.S. was not a major power. It had an army of fewer than 130,000 men, and the anti-war movement was fierce, if not as well remembered as Vietnam. The U.S. was ultimately dragged into World War I when the Germans, who were in a bad way, went back on a pledge not to attack American shipping with U-boats and made Mexico an offer to join the war — on their side.

WWII, of course, needs no introduction: The Nazis invaded Poland on Sept. 1, 1939; the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7, 1941. Adolf Hitler then declared war on the United States and suddenly an isolationist nation was fighting a war on two fronts, in addition to becoming the "arsenal of democracy."

Following WWII, the U.S. didn't crawl back into its shell. It was now a major world power, reconceiving Japan, rebuilding Europe, and facing off with nations living behind the Iron Curtain. If you believe in President Harry S Truman's domino theory, the hot spots in the Cold War — Korea, Japan — were wars of necessity and extensions of previous wars in Europe.

Late Wednesday evening, though, war returned to the bloodlands (as Yale's Timothy Snyder called them). Violence is engulfing Europe again.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Americans must face the fact that no one knows where Russian President Vladimir Putin will stop. Russian troops aren't leaving Belarus any time soon, and soldiers made a brief visit to another former Soviet republic, Kazakhstan, recently.

Of course, Ukraine is not a member of NATO. It wanted to be, but it isn't. The U.S. is under no obligation to fight on Kyiv's behalf. The Baltic states, on the other hand, are NATO members, since 2004, and Article 5 of the NATO treaty says that every other member of the alliance must come to their rescue in event of an invasion. Putin covets Latvia, Estonia, and Lithuania, once Soviet republics and also temptingly geographically desirable.

From a historical standpoint, the U.S. is starting the way it has in other European wars: humanitarian and military aid; tough sanctions and harsh words. American soldiers are racing to reinforce the front lines of member states, though not yet in large numbers.

The U.S. now must face up to the scariest thing about this new war in Europe. No one yet knows whether America will have to fight in it.

Jason Fields is a writer, editor, podcaster, and photographer who has worked at Reuters, The New York Times, The Associated Press, and The Washington Post. He hosts the Angry Planet podcast and is the author of the historical mystery "Death in Twilight."