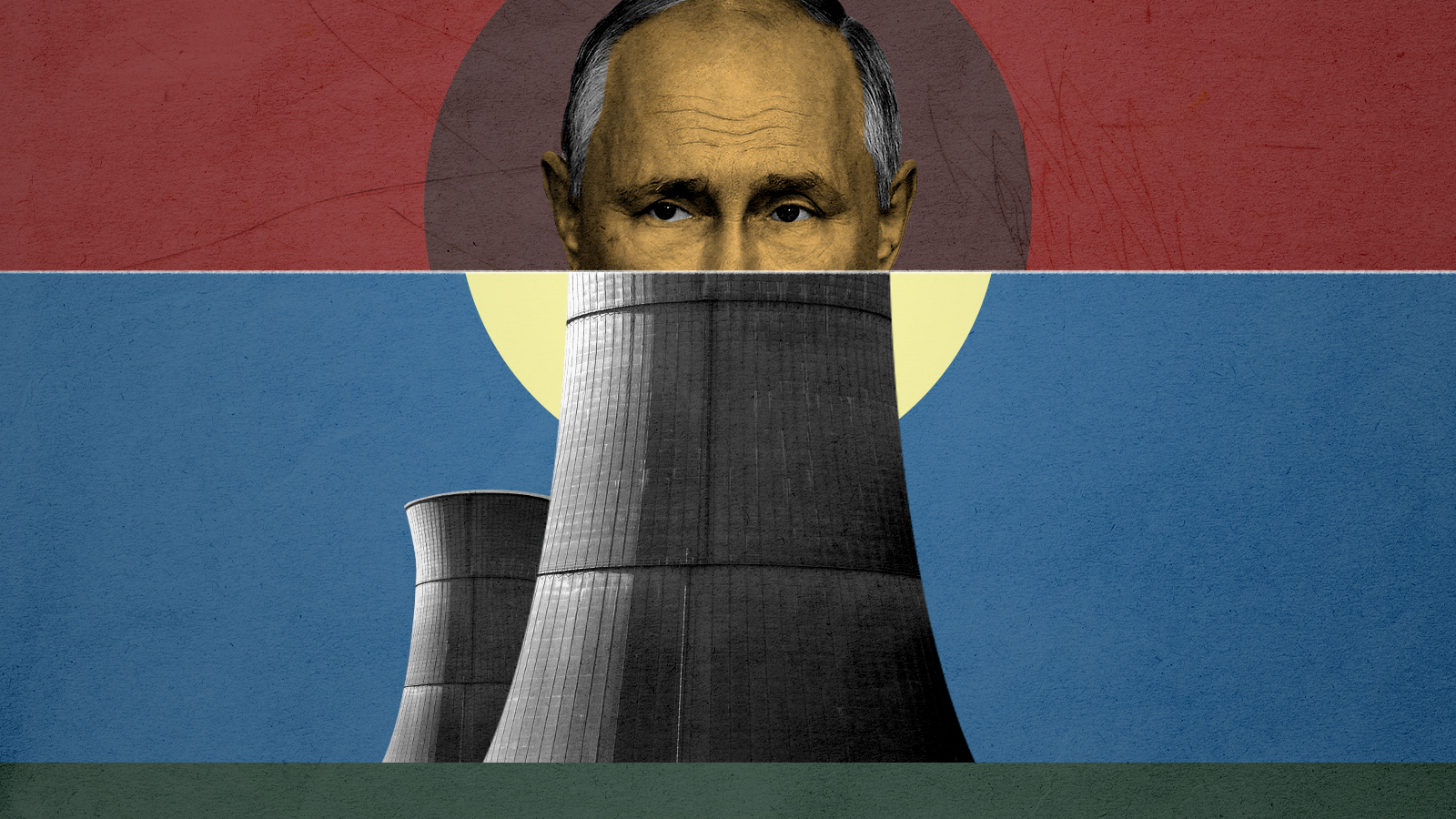

Could war in Ukraine be a deathblow for nuclear power?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Well, that was scary.

On Thursday night, Russian troops invading Ukraine attacked and then seized the nuclear power plant at Zaporizhzhia, briefly starting a fire amid the combat, which raised fears of a new Chernobyl-style radioactive disaster. Those concerns appear to be misplaced, at least for the moment: No radiation was released during the blaze. A lot of people were angry and anxious during those hours, though.

The attack — along with Russia's capture of Chernobyl itself during the first days of the war — almost certainly complicates the arguments of those who see nuclear power as an important part of the effort to wean the world off Russian oil and gas, as well as those who hope to use it to decarbonize the world's energy supplies in order to slow down climate change.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Simply put: Nuclear plants don't really belong in a war zone, do they?

Even before the Russian invasion, there had been a vocal subset of environmentalists who — perhaps counterintuitively — argued that nuclear plants should be part of the climate change agenda. The onset of war initially seemed to give more weight to the pro-nuke arguments. There was even some talk about reversing Germany's decision to shut down all of its nuclear plants. (The country's energy companies say it's too late to reverse the shutdown process in time to make a difference for next winter.)

"People who see nuclear as a part of the overall strategy for dealing with emissions and a way that that also reduces dependence on foreign suppliers are going to see in this a logic for keeping nuclear plants open and for building new nuclear plants in Europe," David Victor, a professor at UC San Diego, told CNBC.

The counterarguments were obvious: Chernobyl. Fukushima. Three Mile Island. Nuclear power has mostly been used safely, but when it goes bad it can go really bad. For most of the last 20 years, terrorism was the human-made problem that caused the most fear. Ukraine has woken us up to the threat of war itself.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

The people running the Zaporizhzhia plant had actually given that possibility some hopeful thought years before the latest conflict.

"There is an assumption that in a situation of an internal conflict neither party will strike at a nuclear plant because of the senselessness of such actions — the consequences may be fatal, not only for those taking action, but also for the aims of the warring parties," Alexey Kovynev, a former shift supervisor and operator at the plant, wrote for Nuclear Engineering International in 2015. While the war with Russia isn't an "internal" conflict, the underlying logic of that assumption turned out to be less true than anybody hoped.

Which creates a problem for nuclear power. If the world is entering a new era of possible violence and instability beyond the conflict's borders — and even if the war ends next week, that might well be the case — putting more radioactive plants in harm's way is going to be a tough sell.

Joel Mathis is a writer with 30 years of newspaper and online journalism experience. His work also regularly appears in National Geographic and The Kansas City Star. His awards include best online commentary at the Online News Association and (twice) at the City and Regional Magazine Association.