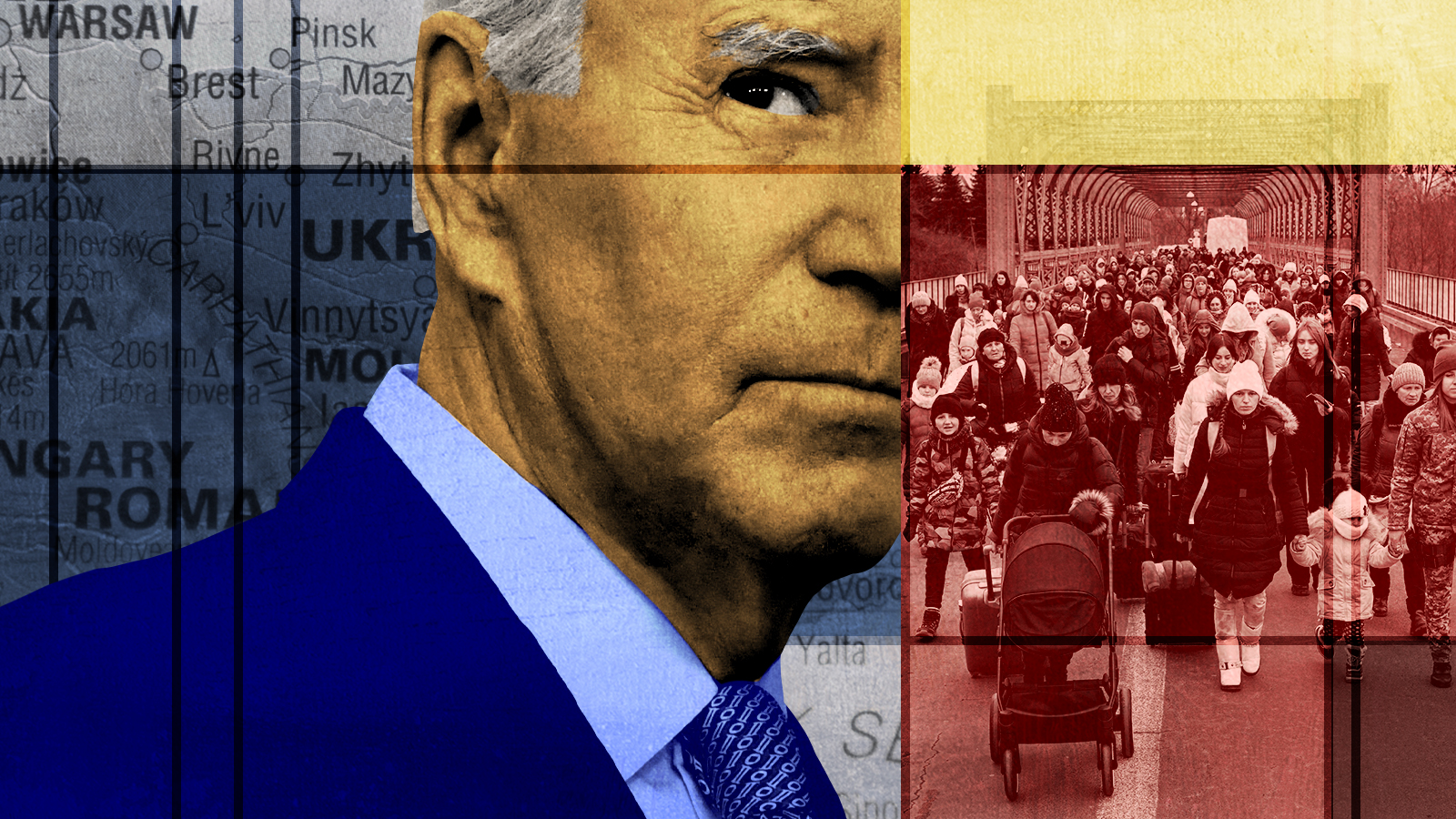

Biden's plan to help Ukrainian refugees

The administration says it will admit up to 100,000 Ukrainian refugees. But how will the program work?

This week, the Department of Homeland Security launched Uniting for Ukraine, a program to help people seeking temporary resettlement in the United States due to the Russian invasion of Ukraine. The Biden administration has said it will admit up to 100,000 Ukrainian refugees forced to flee their homes because of the war, with Uniting for Ukraine one part of a broader initiative. Here's everything you need to know:

What exactly is Uniting for Ukraine?

It's a humanitarian parole program that streamlines the process of getting Ukrainian refugees temporarily settled in the United States. Parole is a way for some individuals to enter and stay in the U.S. for a limited amount of time, without an immigrant or non-immigrant visa, due to "urgent humanitarian reasons or significant public benefit." Parole is determined on a case-by-case basis. President Biden said last week that Uniting for Ukraine "will complement the existing legal pathways available to Ukrainians, including immigrant visas and refugee processing."

Why did the Biden administration decide to create a parole program?

Administration officials say that while speaking with displaced Ukrainians, many shared that they were seeking a safe place to live amid the war, but did not want to permanently resettle outside of Ukraine. Those who come to the U.S. as part of Uniting for Ukraine can stay for up to two years.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

How do you sign up for Uniting for Ukraine?

Ukrainians cannot directly apply themselves. Instead, sponsors who legally live in the United States must fill out an I-134 form; this can be done by an individual or an entity, like a school or nonprofit. The sponsor has to agree to financially support the refugee and ensure they have appropriate housing, and will be vetted to prevent the exploitation of migrants. If the sponsor is approved, the Ukrainian will receive an email from United States Citizenship and Immigration Services, and must then complete several requirements, including biographic and biometric screening.

Which Ukrainian migrants are eligible for Uniting for Ukraine?

The program is open to Ukrainian citizens, as well as their children, spouses, and common-law partners, who left Ukraine after Feb. 11.

How long will the entire process take?

That's unclear, as a lot of it depends on how many people apply for Uniting for Ukraine. The Department of Homeland Security said it "anticipates that the process will be fairly quick," but can't give out any estimates. Typically, it takes between 18 and 24 months to complete the U.S. refugee process.

What happens once someone is paroled into the United States?

They have 90 days to enter the U.S. and have to arrange their own travel. Before arriving, they must also receive some vaccinations and complete other public health requirements. Once in the U.S., Ukrainian refugees are eligible to apply for employment authorization and encouraged to sign up for a Social Security number. They may also qualify for some government programs, including emergency Medicaid and Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) services and benefits. Their parole will be valid for a period of up to two years, and will be automatically terminated if they leave the United States without receiving prior authorization.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

How will Uniting for Ukraine affect Ukrainians trying to enter the U.S. at the southern border?

Part of Uniting for Ukraine's goal is to deter Ukrainians from attempting to enter the U.S. at land ports of entry; now that the program is up and running, refugees who do arrive at the border without valid visas or pre-authorization to cross may be denied entry, the Department of Homeland Security said. After Russia launched its invasion of Ukraine on Feb. 24, many Ukrainians hoping to ultimately settle in the United States first traveled to Mexico, where it's easier to get a visa, and then sought entry to the U.S. at the southern border. U.S. Customs and Border Protection officials said that in March, it processed 3,274 Ukrainians there — an increase of more than 1,100 percent from February, CBS News reports. A senior Homeland Security official told reporters that in total, U.S. immigration officials have processed nearly 15,000 undocumented Ukrainians over the past three months.

Catherine Garcia has worked as a senior writer at The Week since 2014. Her writing and reporting have appeared in Entertainment Weekly, The New York Times, Wirecutter, NBC News and "The Book of Jezebel," among others. She's a graduate of the University of Redlands and the Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism.

-

Why quitting your job is so difficult in Japan

Why quitting your job is so difficult in JapanUnder the Radar Reluctance to change job and rise of ‘proxy quitters’ is a reaction to Japan’s ‘rigid’ labour market – but there are signs of change

-

Gavin Newsom and Dr. Oz feud over fraud allegations

Gavin Newsom and Dr. Oz feud over fraud allegationsIn the Spotlight Newsom called Oz’s behavior ‘baseless and racist’

-

‘Admin night’: the TikTok trend turning paperwork into a party

‘Admin night’: the TikTok trend turning paperwork into a partyThe Explainer Grab your friends and make a night of tackling the most boring tasks

-

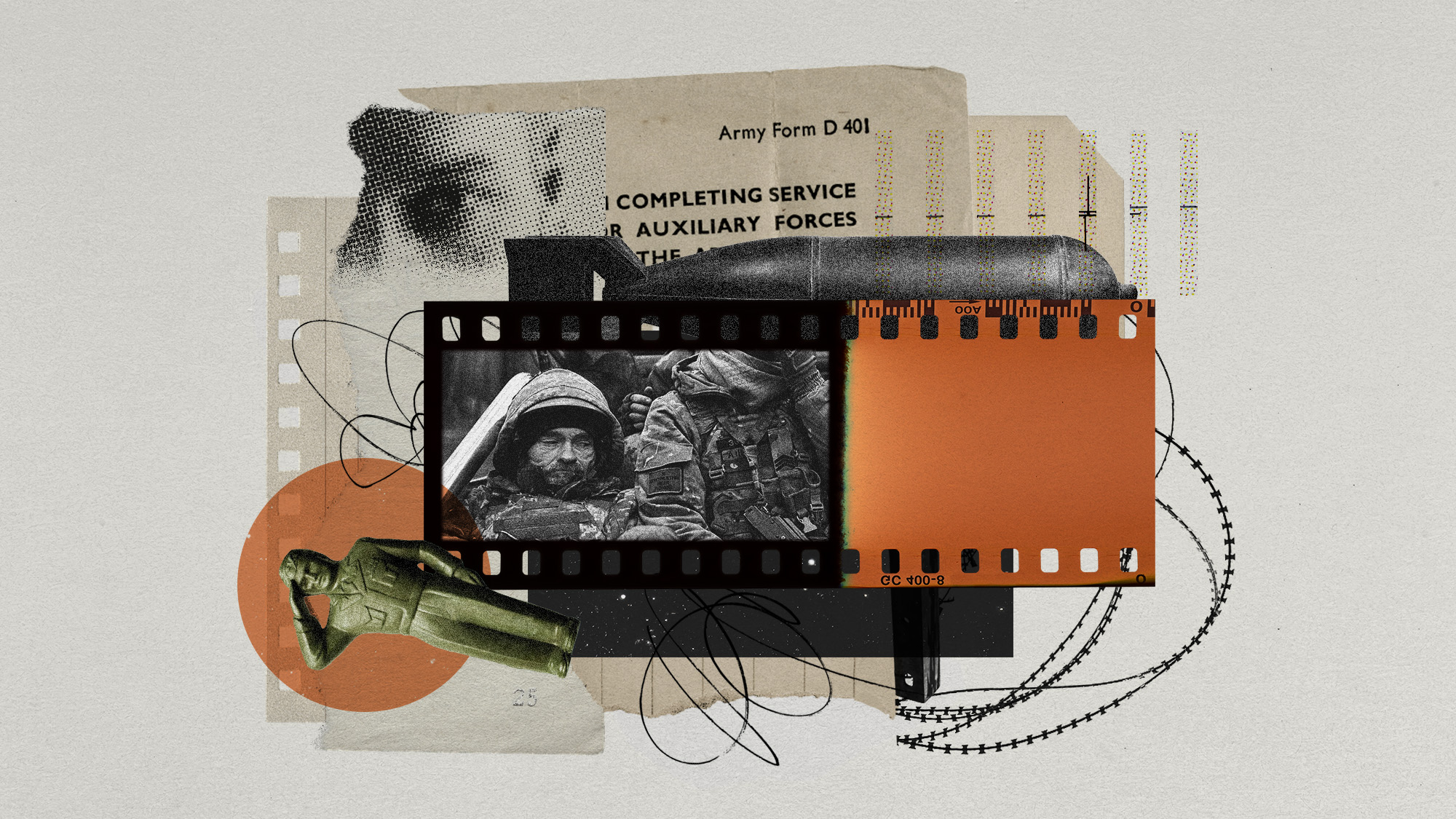

The mission to demine Ukraine

The mission to demine UkraineThe Explainer An estimated quarter of the nation – an area the size of England – is contaminated with landmines and unexploded shells from the war

-

The secret lives of Russian saboteurs

The secret lives of Russian saboteursUnder The Radar Moscow is recruiting criminal agents to sow chaos and fear among its enemies

-

Is the 'coalition of the willing' going to work?

Is the 'coalition of the willing' going to work?Today's Big Question PM's proposal for UK/French-led peacekeeping force in Ukraine provokes 'hostility' in Moscow and 'derision' in Washington

-

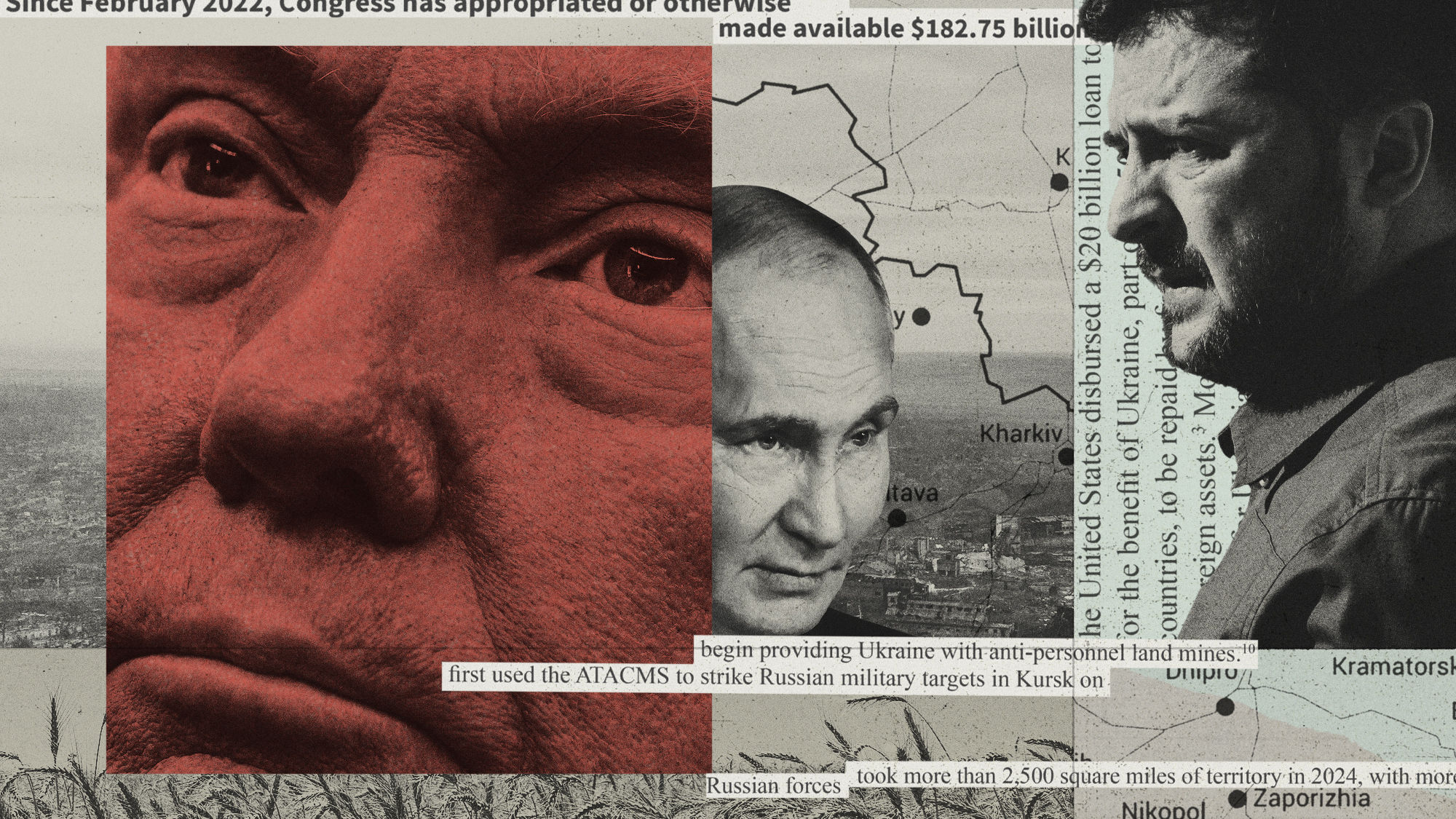

Ukraine: where do Trump's loyalties really lie?

Ukraine: where do Trump's loyalties really lie?Today's Big Question 'Extraordinary pivot' by US president – driven by personal, ideological and strategic factors – has 'upended decades of hawkish foreign policy toward Russia'

-

What will Trump-Putin Ukraine peace deal look like?

What will Trump-Putin Ukraine peace deal look like?Today's Big Question US president 'blindsides' European and UK leaders, indicating Ukraine must concede seized territory and forget about Nato membership

-

Ukraine's disappearing army

Ukraine's disappearing armyUnder the Radar Every day unwilling conscripts and disillusioned veterans are fleeing the front

-

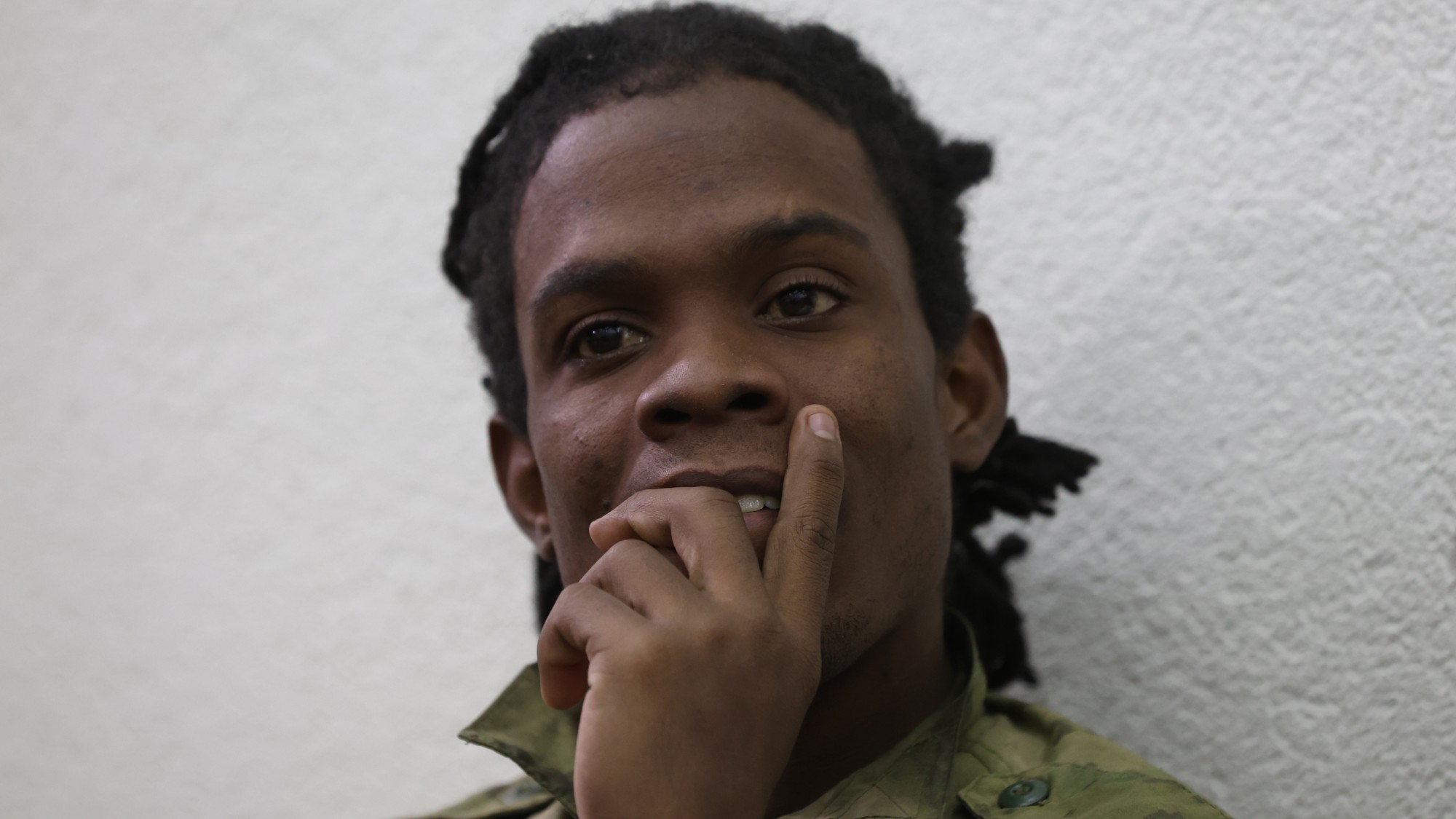

Cuba's mercenaries fighting against Ukraine

Cuba's mercenaries fighting against UkraineThe Explainer Young men lured by high salaries and Russian citizenship to enlist for a year are now trapped on front lines of war indefinitely

-

Ukraine-Russia: are both sides readying for nuclear war?

Ukraine-Russia: are both sides readying for nuclear war?Today's Big Question Putin changes doctrine to lower threshold for atomic weapons after Ukraine strikes with Western missiles