Ukraine's mysterious battle to retake Kherson

'All the details will be available after the operation is fulfilled'

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Ukraine has been talking about launching a major counteroffensive in southern Kherson province since July, fighting to recapture at least the regional capital, Kherson City, from Russian invaders who seized the region soon after their Feb. 24 invasion. On Monday, Ukraine said the offensive had begun — then said little else.

Ukrainian forces "have started the offensive actions in several directions on the South front towards liberating the occupied territories," Nataliya Humeniuk, a spokeswoman for Ukraine's southern military command, told CNN. "All the details will be available after the operation is fulfilled." Yes, "there is news," she told The Wall Street Journal. "It has inspired everyone. We need to be patient."

By the end of the first week, it still wasn't clear how the battle was going — or even if this is the big counterpunch Ukraine has been telegraphing. Here's a look at what we know and what it could mean for the shape of the war:

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Why is Ukraine focusing its counteroffensive on Kherson?

First of all, "Kherson was the first strategically important city captured by Russia at the start of the invasion in late February, and the broader Kherson region helps form Russian President Vladimir Putin's coveted 'land bridge' to Crimea," The Washington Post reports. Taking back Kherson City, the regional capital and a "major economic hub" between the Dnieper River and the Black Sea, would provide a big morale boost to the Ukrainian army.

Ukraine originally considered a broader counteroffensive but narrowed the scope to the Kherson region in recent weeks after "war-gaming" with the U.S. military, U.S. and Western officials and Ukrainian sources told CNN. After workshopping what force levels would be needed to be successful in various scenarios, Ukraine agreed that a large offensive would risk overextending its limited resources.

Why the radio silence?

Ukraine is giving two main reasons for limiting the information available on its counteroffensive: the safety of journalists covering the war and tactical imperatives.

"Military officials have barred reporters from accessing front-line areas across the country through at least Monday, a level of restrictions unprecedented in the six months since the start of the Russian onslaught," the Post reports. "They have asked Ukrainians to be patient and warned that operational security means information about the campaign will be slow to emerge."

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

And Ukrainian officials aren't wrong, the Institute for the Study of War think tank explains. Ukraine doesn't have the troop strength or military hardware to blitz Kherson, and "military forces that must conduct offensive operations without the numerical advantages normally required for success in such operations often rely on misdirections and feints," ISW writes. A pause in all "reporting or forecasting of the Ukrainian counteroffensive" is "essential if the counteroffensive includes feints or misdirections."

Is Russia also maintaining operational silence?

No. Russia says the counteroffensive is real, and claims Ukraine is failing, with limited gains and huge casualties.

Take that with a big grain of salt, ISW advises. "The Russian Ministry of Defense began conducting an information operation to present Ukraine's counteroffensive as decisively failed almost as soon as it was announced," and Ukrainians and the West shouldn't mistake Ukraine's operational silence as confirmation for Russia's narrative.

"It is of course possible that the counteroffensive will fail," ISW concedes. "But the situation in which Ukraine finds itself calls for a shrewd and nuanced counteroffensive operation with considerable misdirection and careful and controlled advances. It is far more likely in these very early days, therefore, that a successful counteroffensive would appear to be stalling or unsuccessful for some time before its success became manifest."

What is Ukraine telling us about the offensive?

Ukrainian officials pretty quickly said Ukrainian forces had broken through Russia's first lines of defense in Kherson, listing four villages Ukraine recapture and the bridges and pontoon crossings its artillery and airstrikes destroyed. "The enemy suffers quite significant losses — losses in manpower have gone from tens to hundreds," and its "equipment also burns," Ukraine's Humeniuk said Friday. "Our successes are quite convincing, and I think very soon we will be able to disclose more positive news."

At the same time, "don't expect any quick victories," BBC News security correspondent Frank Gardner writes. "Ukrainian officials have hinted this is more likely to be a long, slow process of wearing down the Russian invaders, breaking their morale by targeting their supply lines using long-range artillery. A lot of those Russian soldiers won't want to be there while Ukrainians have a patriotic interest in regaining their land."

The offensive is "going to take as long as needed and nobody is going to rush it because people expect something dramatic and exciting," Andriy Zagorodnyuk, former Ukrainian defense minister and chair of a military think tank in Kyiv, tells the Post. "They're going to be doing it safely, whatever time it takes."

What are we learning from other sources?

Reporters on the outskirts of the fighting report that the pace of battle and intensity of artillery fire have both increased.

Ukraine's armored forces "have pushed the front line back some distance in places, exploiting relatively thinly held Russian defenses," Britain's Ministry of Defense wrote. Russia is suffering "severe manpower shortages" in Ukraine and is getting increasingly desperate to get new troops to the front lines, a U.S. intelligence report released Wednesday found.

Russia is suffering "severe manpower shortages" in its 6-month-old war with Ukraine and has become more desperate in its efforts to find new troops to send to the front lines, according to a new American intelligence finding disclosed Wednesday. Part of Moscow's new strategy is reportedly recruiting convicted criminals and offering them pay and pardons to fight in Ukraine.

"We are very sensitive to not getting ahead of the Ukrainians," but "what I will say is that we are aware of Ukrainian military operations that have made some forward movement, and in some cases, in the Kherson region, we are aware, in some cases, of Russian units falling back," Pentagon spokesman Brig. Gen. Pat Ryder said at a press briefing Wednesday. "But again, in order to preserve operation security and to give the Ukrainians the time and the space that they need to conduct their operations."

"Ukrainians can sense that momentum is shifting in their favor," retired Lt. Gen. Ben Hodges, a former commander of the U.S. Army in Europe, tells the Journal. This offensive "will make it much more feasible for Ukraine's supporters, as well as Ukrainians, to envision the recovery of Ukraine. It will continue to remove the idea that Russian victory is inevitable." And as for the thousands of Russian troops all but trapped on the Dnipro's western bank, "they haven't been properly resupplied," he added. "Their chances of getting out of there are not good."

Peter has worked as a news and culture writer and editor at The Week since the site's launch in 2008. He covers politics, world affairs, religion and cultural currents. His journalism career began as a copy editor at a financial newswire and has included editorial positions at The New York Times Magazine, Facts on File, and Oregon State University.

-

The Olympic timekeepers keeping the Games on track

The Olympic timekeepers keeping the Games on trackUnder the Radar Swiss watchmaking giant Omega has been at the finish line of every Olympic Games for nearly 100 years

-

Will increasing tensions with Iran boil over into war?

Will increasing tensions with Iran boil over into war?Today’s Big Question President Donald Trump has recently been threatening the country

-

Corruption: The spy sheikh and the president

Corruption: The spy sheikh and the presidentFeature Trump is at the center of another scandal

-

The mission to demine Ukraine

The mission to demine UkraineThe Explainer An estimated quarter of the nation – an area the size of England – is contaminated with landmines and unexploded shells from the war

-

The secret lives of Russian saboteurs

The secret lives of Russian saboteursUnder The Radar Moscow is recruiting criminal agents to sow chaos and fear among its enemies

-

Is the 'coalition of the willing' going to work?

Is the 'coalition of the willing' going to work?Today's Big Question PM's proposal for UK/French-led peacekeeping force in Ukraine provokes 'hostility' in Moscow and 'derision' in Washington

-

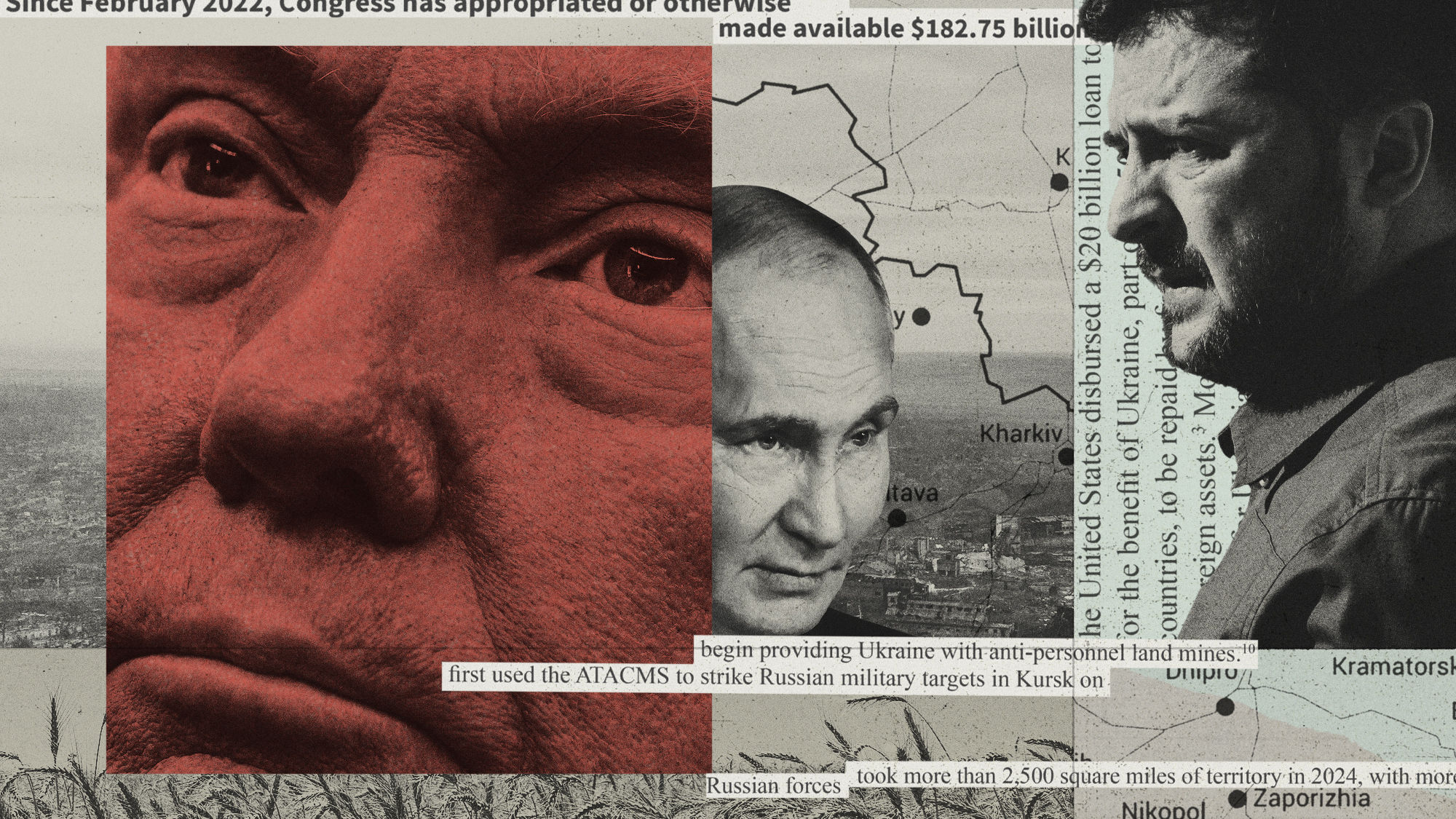

Ukraine: where do Trump's loyalties really lie?

Ukraine: where do Trump's loyalties really lie?Today's Big Question 'Extraordinary pivot' by US president – driven by personal, ideological and strategic factors – has 'upended decades of hawkish foreign policy toward Russia'

-

What will Trump-Putin Ukraine peace deal look like?

What will Trump-Putin Ukraine peace deal look like?Today's Big Question US president 'blindsides' European and UK leaders, indicating Ukraine must concede seized territory and forget about Nato membership

-

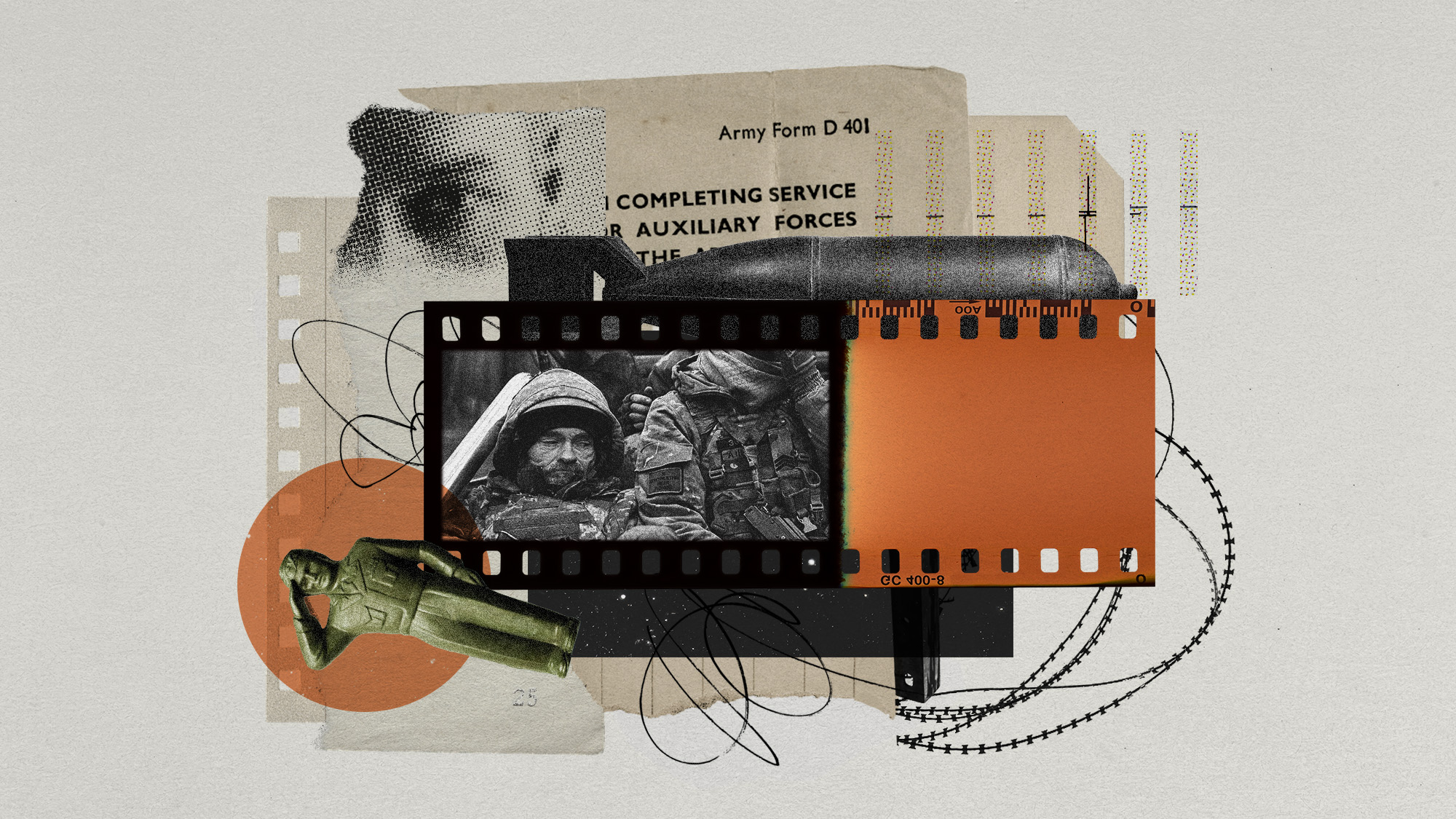

Ukraine's disappearing army

Ukraine's disappearing armyUnder the Radar Every day unwilling conscripts and disillusioned veterans are fleeing the front

-

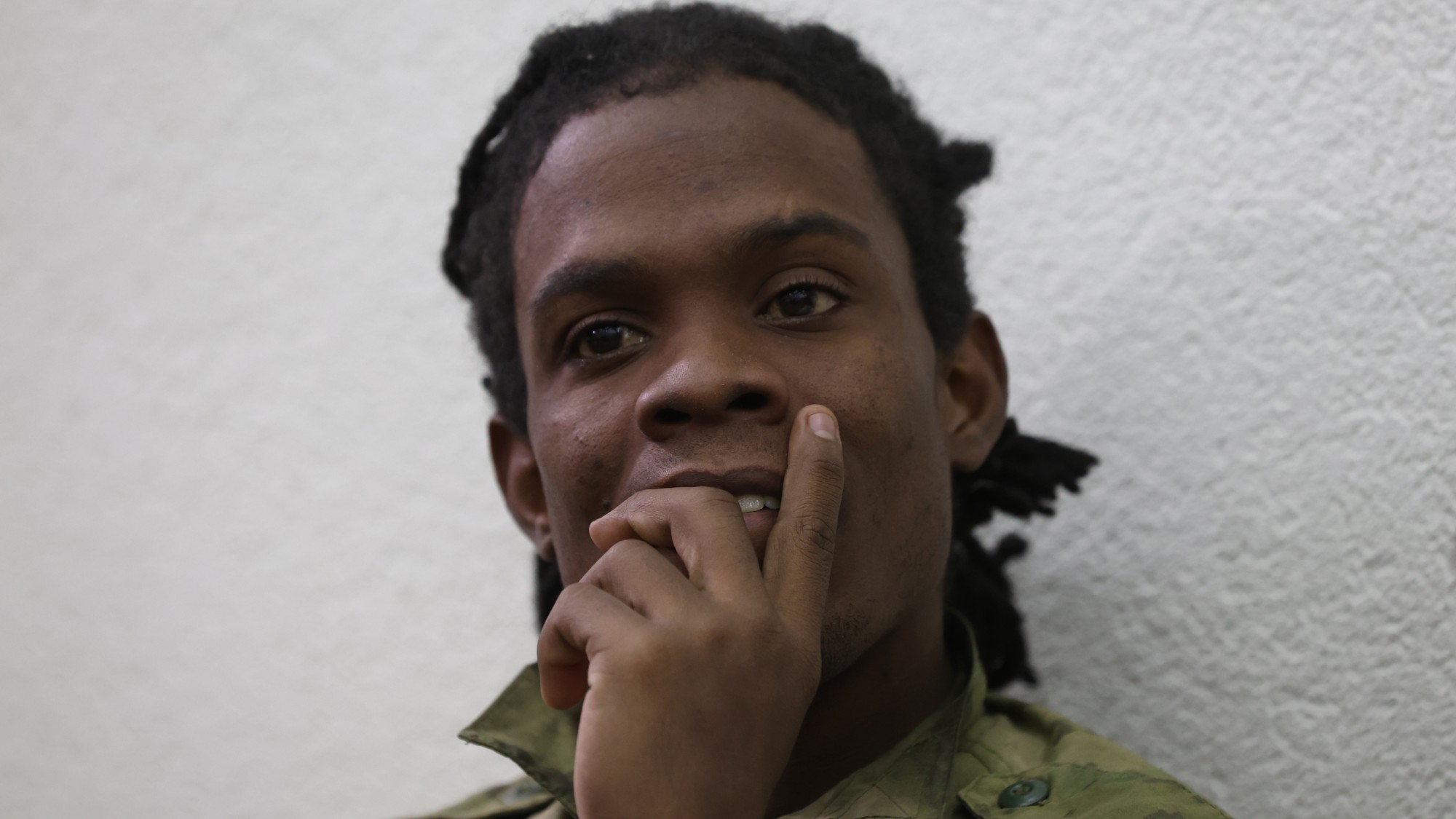

Cuba's mercenaries fighting against Ukraine

Cuba's mercenaries fighting against UkraineThe Explainer Young men lured by high salaries and Russian citizenship to enlist for a year are now trapped on front lines of war indefinitely

-

Ukraine-Russia: are both sides readying for nuclear war?

Ukraine-Russia: are both sides readying for nuclear war?Today's Big Question Putin changes doctrine to lower threshold for atomic weapons after Ukraine strikes with Western missiles