How to prevent another grim pandemic winter

Vaccines, more vaccines, and masks

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Europe is suffering another surge of coronavirus cases, particularly in the east, as winter approaches and people head indoors. Given the generally high level of vaccination across much of the continent, it's an alarming development.

However, all is not lost. Europe is not as universally vaccinated as you may suppose, and shots are still the most powerful tool in the pandemic-fighting arsenal. Mandatory vaccinations, booster doses, and sticking with control measures like masks might just allow much of Europe — and some American states — to head off another brutal pandemic winter.

Eyeballing the data, there are two plausible explanations for what is going on in Europe. The first is inadequate vaccination: There is a clear inverse relationship between shots and spread. The countries suffering truly galloping outbreaks — mostly places to the south and east like Greece, Austria, Hungary, Slovenia, and Slovakia — are typically below 70 percent full vaccination, often quite far below. By contrast, there appears to be a rough breakpoint near 75-80 percent vaccination where the rate of case growth is much slower. It's surely not a coincidence Portugal and Spain are the most-vaccinated countries on the continent, and both have thus far mostly avoided a big resurgence.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Now, this trend is not totally consistent. Ireland (75 percent) is doing considerably worse than other countries near its same level of vaccination, while Sweden is doing quite a bit better. This could be down to local peculiarities — Ireland has a lot of large families, while Sweden had a massive number of prior infections that could be boosting its level of immunity — or just the random happenstance that is a feature of all pandemics.

Alas, probably not even the most-vaccinated country in Europe — Portugal, at 88 percent — has reached herd immunity. The larger the fraction of the population that is vaccinated, the better, but for the virus to fizzle out entirely will require a very high level of coverage. If you plug the Delta variant's extreme contagiousness into a simple formula for what level of immunity is needed, you get a figure of about 85 percent — but unfortunately, none of the shots are 100 percent effective.

Worse, the initial vaccine-built immunity fades. The latest research has found the level of protection instilled by the first two doses of vaccine tends to wane over time, from over 90 percent protection against infection to maybe 55-70 percent. Thus, as this year has progressed, more vaccinated people have gotten sick or even died — though the rates of serious illness or death among the vaccinated are still vastly lower than among unvaccinated folks. (Remember, even though the vaccine does not provide 100 percent protection against infection, it still drastically reduces the severity of a COVID case if you do catch it. You would much rather have what amounts to a bad flu than spend a month in intensive care.)

I would guess declining immunity is the main reason even Portugal is still seeing an increasing caseload, albeit a modest one with very few deaths. It may well see some serious spread in future, though I would be shocked to see anything like what is happening in Austria.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Luckily, there is a solution here: booster shots. A recent study on the Pfizer/BioNTech vaccine showed that with a booster, effectiveness at preventing infection jumped back to 96 percent against Delta, and other vaccines seem to show the same thing. Data from Israel and the U.K. prove that boosters do indeed raise immunity and slow the spread. If Portugal could get to 90 percent boosted, then the math says that ought to be sufficient for real herd immunity.

Many vaccines have this kind of a widely-spaced interval, and it may turn out that would have been the best approach all along. And like the tetanus or Hepatitis B vaccines, some scientists suspect the immunity from a booster shot should last longer than the initial doses — perhaps even being permanent.

Bringing this all together, we see several obvious recommendations for policymakers. The first is still the most obvious step: Vaccinate the unvaccinated, including children, by hook or by crook. All available research shows that the vaccines are tolerated very well — and with 7.4 billion doses administered at the time of writing, any serious side effects would be extremely obvious by now. Pay people; require it to enter restaurants or workplaces; go door to door with dart guns. Do whatever it takes.

Second, roll out booster shots. Now, it is unfair that Africa is so far behind in vaccination while rich countries are considering third doses, but the world is fairly close to plentiful vaccine supply. African nations are finally starting to get significant supply, and realistically America and Europe should be able to roll out boosters at a decent pace while still making deliveries to the Covax program for poorer nations. In any case, administration rather than supply is quickly becoming the bottleneck in many poorer places — the Democratic Republic of the Congo had to return 1.3 million doses it couldn't administer, while Tanzania is struggling to give out the shots it has thanks to a misinformation campaign from the former president (who died of COVID himself).

Third, keep at least a baseline of pandemic control measures in place. Things like mask requirements in indoor spaces, enabling outdoor dining, building capacity limits, ventilation upgrades, distribution of HEPA filters, and so on will make it harder for the disease to spread and therefore make it easier to approach herd immunity.

As I have previously written, the coronavirus is never going to be totally eradicated. But if governments press ahead with sensible policies, they might just be able to keep a lid on it until vaccination reaches a point where COVID will just become another relatively minor annoyance, like the flu.

Ryan Cooper is a national correspondent at TheWeek.com. His work has appeared in the Washington Monthly, The New Republic, and the Washington Post.

-

Crisis in Cuba: a ‘golden opportunity’ for Washington?

Crisis in Cuba: a ‘golden opportunity’ for Washington?Talking Point The Trump administration is applying the pressure, and with Latin America swinging to the right, Havana is becoming more ‘politically isolated’

-

5 thoroughly redacted cartoons about Pam Bondi protecting predators

5 thoroughly redacted cartoons about Pam Bondi protecting predatorsCartoons Artists take on the real victim, types of protection, and more

-

Palestine Action and the trouble with defining terrorism

Palestine Action and the trouble with defining terrorismIn the Spotlight The issues with proscribing the group ‘became apparent as soon as the police began putting it into practice’

-

A Nipah virus outbreak in India has brought back Covid-era surveillance

A Nipah virus outbreak in India has brought back Covid-era surveillanceUnder the radar The disease can spread through animals and humans

-

Covid-19 mRNA vaccines could help fight cancer

Covid-19 mRNA vaccines could help fight cancerUnder the radar They boost the immune system

-

The new Stratus Covid strain – and why it’s on the rise

The new Stratus Covid strain – and why it’s on the riseThe Explainer ‘No evidence’ new variant is more dangerous or that vaccines won’t work against it, say UK health experts

-

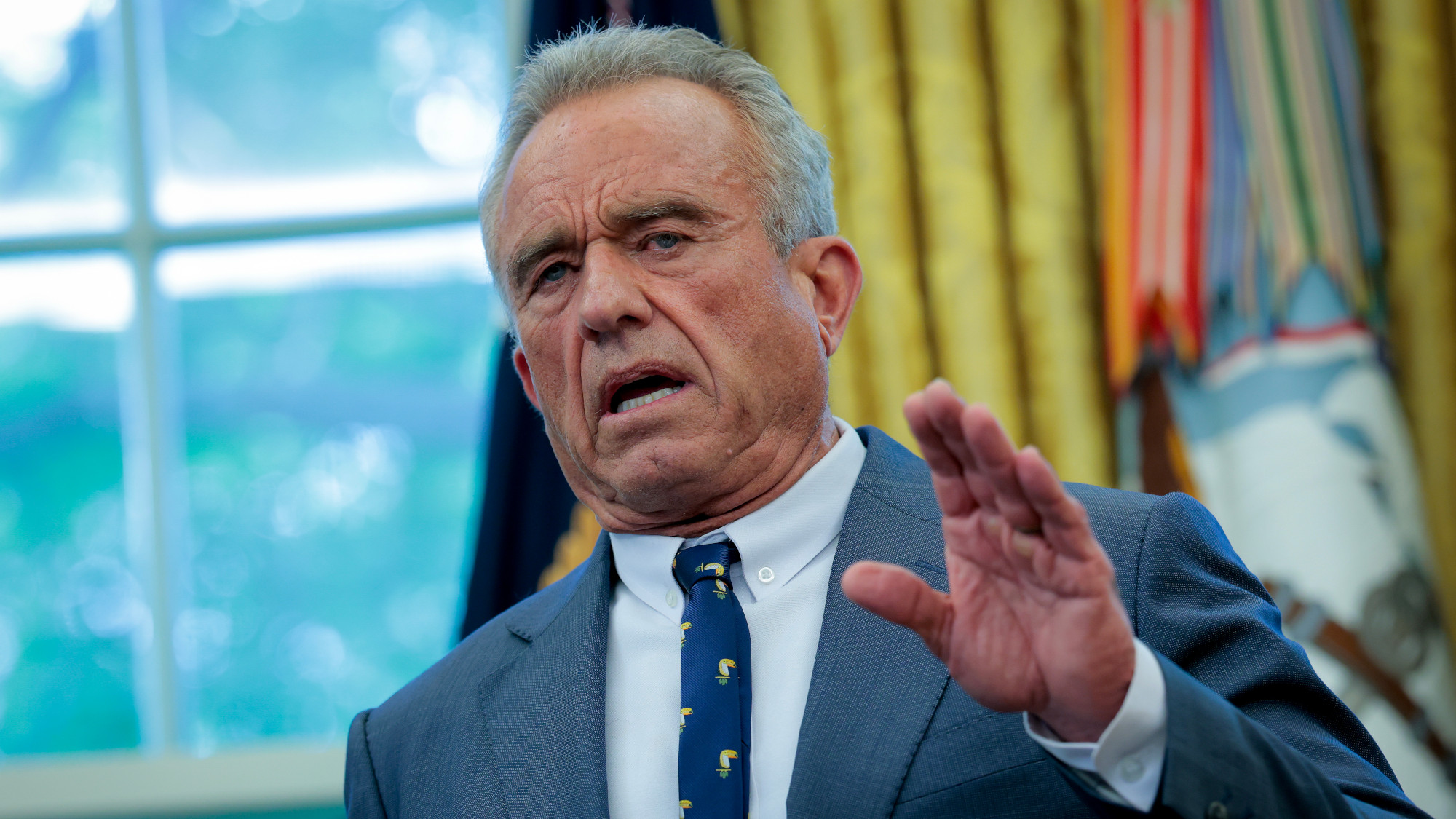

RFK Jr. vaccine panel advises restricting MMRV shot

RFK Jr. vaccine panel advises restricting MMRV shotSpeed Read The committee voted to restrict access to a childhood vaccine against chickenpox

-

RFK Jr. scraps Covid shots for pregnant women, kids

RFK Jr. scraps Covid shots for pregnant women, kidsSpeed Read The Health Secretary announced a policy change without informing CDC officials

-

New FDA chiefs limit Covid-19 shots to elderly, sick

New FDA chiefs limit Covid-19 shots to elderly, sickspeed read The FDA set stricter approval standards for booster shots

-

RFK Jr.: A new plan for sabotaging vaccines

RFK Jr.: A new plan for sabotaging vaccinesFeature The Health Secretary announced changes to vaccine testing and asks Americans to 'do your own research'

-

Five years on: How Covid changed everything

Five years on: How Covid changed everythingFeature We seem to have collectively forgotten Covid’s horrors, but they have completely reshaped politics