Everything you need to know about the big black hole at the center of our galaxy

Sagittarius A* is massive and massively important

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

On Thursday, astronomers unveiled the first-ever image of Sagittarius A*, the supermassive black hole at the center of the Milky Way galaxy. Researchers from around the world worked together to make this never-before-seen picture — which confirms Albert Einstein's general theory of relativity — happen. Here's everything you need to know:

What is a black hole?

A black hole is the densest object in the universe, creating a gravitational field so strong even light can't escape it. The largest types of black holes are "supermassive," meaning they have the mass of more than 1 million suns smushed together into a space the size of a single star, NASA says. Sagittarius A* — pronounced "Sagittarius A star" — has a mass equal to about 4 million suns. As Space.com writes, "Black holes are notoriously difficult to spot" and are "usually only inferred by the effects they have on their environment. This is because not only do they not emit light, but black holes also trap photons behind a boundary called the event horizon, making studying them directly in optical light near impossible."

How was the image of Sagittarius A* captured?

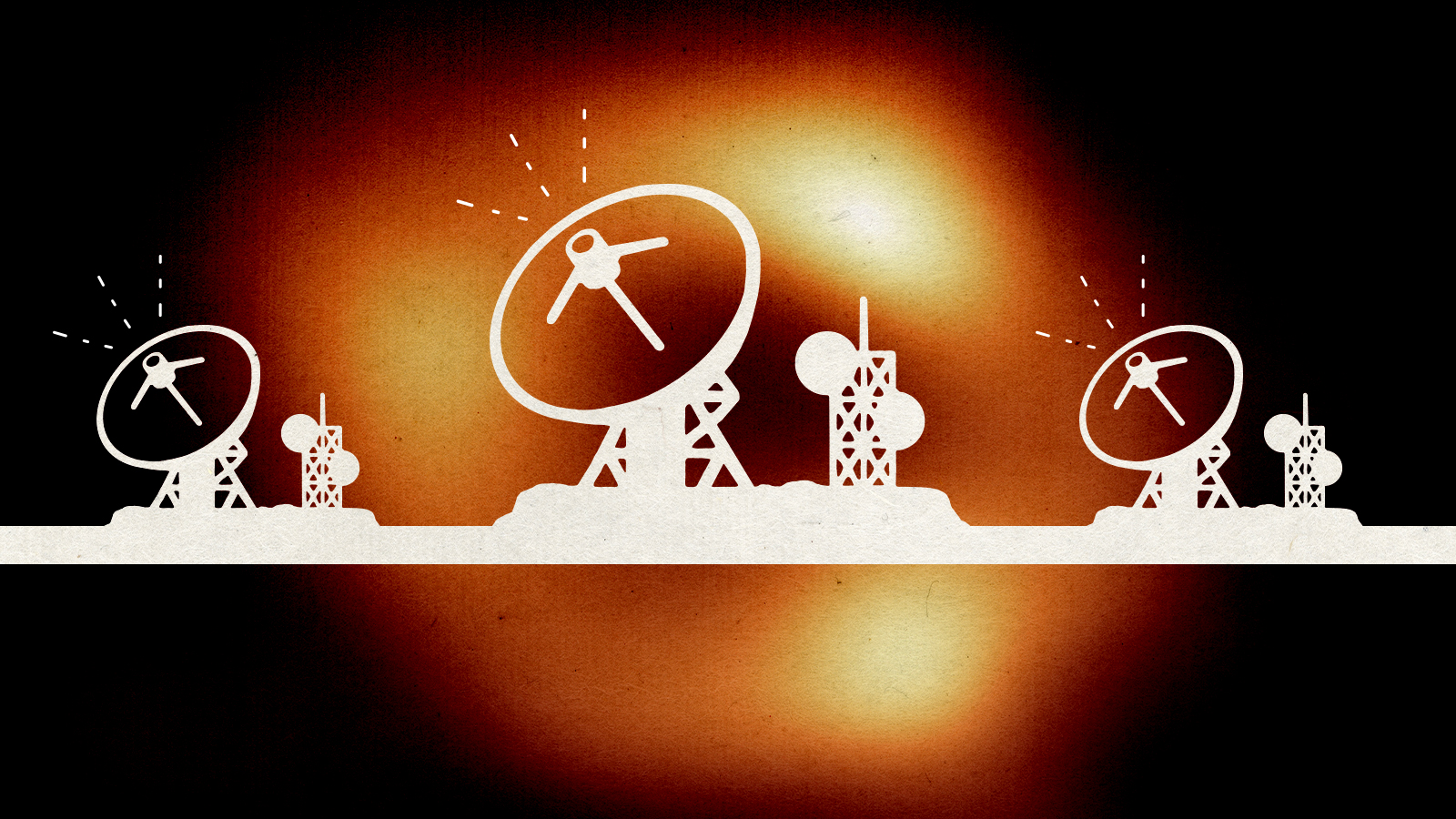

The colorized image was captured as part of the Event Horizon Telescope research project, which involves more than 300 scientists from 13 global institutions and eight synchronized radio telescopes. As The Wall Street Journal explains, the array "can pick up radio waves given off by gas and dust moving near a black hole's event horizon." Using a technique known as Very Long Baseline Interferometry, all of the data from these radio telescopes was combined into one image, as if it came from a single giant telescope.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

In 2019, the Event Horizon Telescope captured an image of a supermassive black hole in M-87, an elliptical galaxy about 55 million light years away in the constellation Virgo. "We have seen what we thought was unseeable," Shep Doeleman, a director of the Event Horizon Telescope and a radio astronomer at the Harvard Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, said at the time.

It was harder to capture a clear image of Sagittarius A* because it "burbled and gurgled as we looked at it," Feryal Özel, an astrophysicist at the University of Arizona, said on Thursday. While observing the M-87 black hole, astronomers found that it didn't move much over the course of a week, while Sagittarius A* "evolves more than a thousand times faster, changing its appearance as often as every five minutes," The New York Times reports. Ultimately, getting the image of Sagittarius A* was, CBS News writes, "a feat roughly equivalent to photographing a single grain of salt in New York City using a camera in Los Angeles."

What else do we know about Sagittarius A*?

Sagittarius A* is about 27,000 light years away from Earth. Before the image was captured of Sagittarius A*, "we didn't have the direct picture to prove that this gentle giant in the center of our galaxy is a black hole," Özel said. "It shows a bright ring surrounding the darkness, and the telltale sign of the shadow of the black hole."

Knowledge of the existence of Sagittarius A* dates back to the early 1930s, when physicist Karl Jansky found a radio signal being emitted from a location in the direction of the Sagittarius constellation. In the 1970s, astronomers Bruce Balick and Robert L. Brown identified Sagittarius A* as a galactic center compact radio source, and a decade later, researchers "formulated the idea that the central compact object was likely to be a black hole of a size — until then — unimaginable," Space.com writes.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Why are astronomers calling Sagittarius A* "a gentle giant?"

Unlike the M-87 black hole, Sagittarius A* is only accumulating "a trickle of material," Michael Johnson, a researcher at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, said on Thursday. If Sagittarius A* was a person, he added, "it would consume a single grain of rice every million years."

Some black holes are "remarkably efficient at converting gravitational energy into light," but Sagittarius A* only converts one part in 1,000 into light, Johnson explained. "So despite looking so bright on the simulated images, the black hole is ravenous but inefficient," he said. "It's only putting out a few hundred times as much energy as the sun despite being 4 million times as massive. The only reason we can study it at all is because it's in our own galaxy."

What are astronomers learning from this image?

Lots of things. Johnson said the black hole is "extraordinary verification of Einstein's general theory of relativity," as it is the size it should be, per his equations. Astronomers can also now compare and contrast the image of Sagittarius A* with the image of the M-87 black hole, and test theories about how gas behaves around supermassive black holes.

Catherine Garcia has worked as a senior writer at The Week since 2014. Her writing and reporting have appeared in Entertainment Weekly, The New York Times, Wirecutter, NBC News and "The Book of Jezebel," among others. She's a graduate of the University of Redlands and the Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism.

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?Today’s Big Question Democrats want to rein in ICE’s immigration crackdown

-

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

5 of the most invasive animal species on the planet

5 of the most invasive animal species on the planetSpeed Read Invasive species are a danger to ecosystems all over the world

-

Air pollution is now the 'greatest external threat' to life expectancy

Air pollution is now the 'greatest external threat' to life expectancySpeed Read Climate change is worsening air quality globally, and there could be deadly consequences

-

How climate change is impacting the water cycle

How climate change is impacting the water cycleSpeed Read Rain will likely continue to be unpredictable

-

Why spotted lanternflies are back and worse than ever

Why spotted lanternflies are back and worse than everSpeed Read It's time to get squashing!

-

Peatlands are the climate bomb waiting to explode

Peatlands are the climate bomb waiting to explodeSpeed Read The destruction of peatlands can cause billions of tons of carbon to be released into the atmosphere, worsening the already intensifying climate crisis

-

Wind-powered ships are back. But will they make an impact?

Wind-powered ships are back. But will they make an impact?Speed Read The maritime industry is eyeing a pivot back to basics

-

The growing threat of urban wildfires

The growing threat of urban wildfiresSpeed Read Maui's fire indicates a phenomenon that will likely become more common

-

A summer of shark attacks

A summer of shark attacksSpeed Read A spate of shark attacks off the Northeast coast has swimmers and surfers on edge. What’s behind the biting spree?