Abandoned mines pose hidden safety and environmental risks

People can be swallowed up by sinkholes — and there are other risks too

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

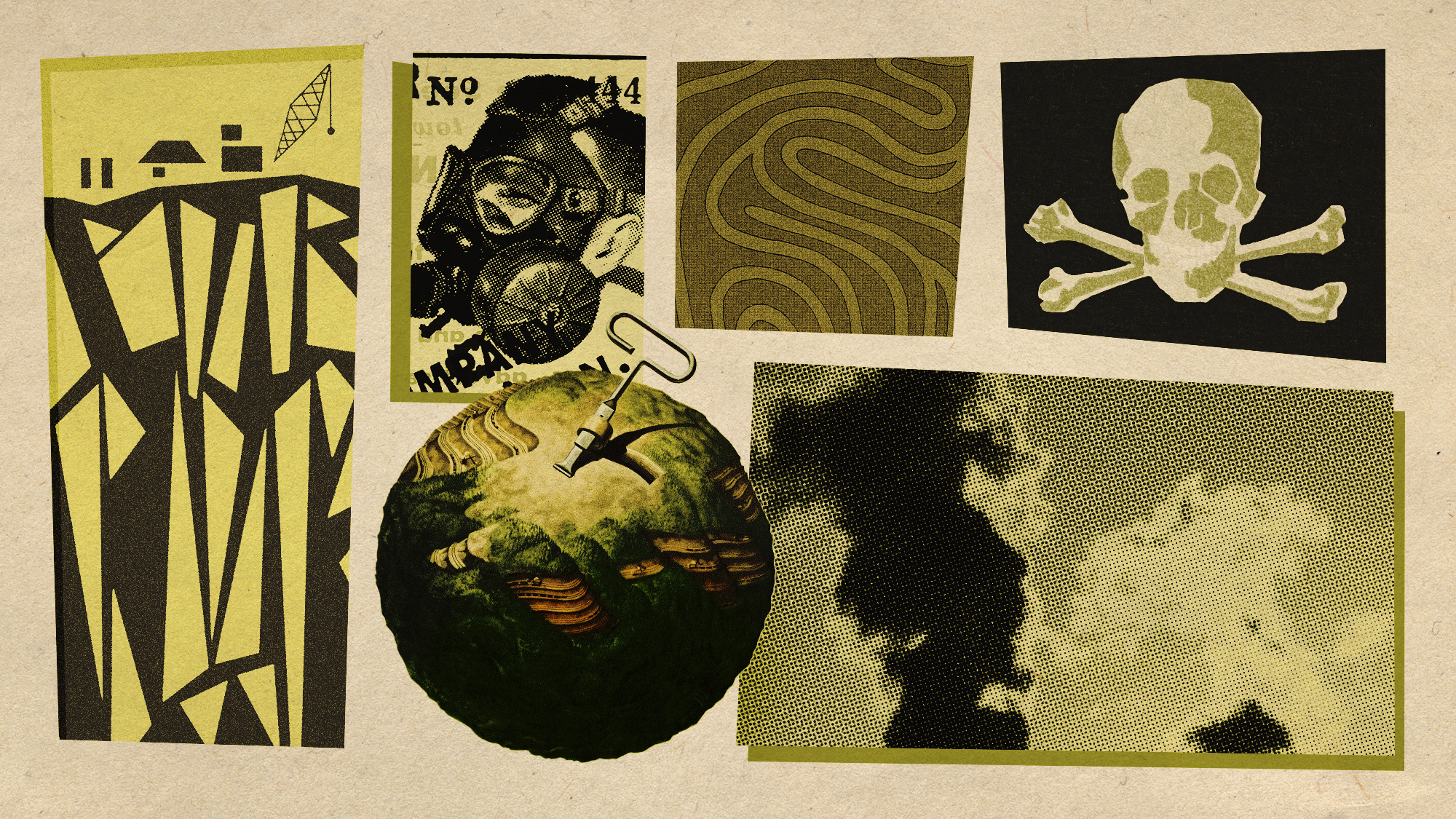

There are about 500,000 abandoned mines in the United States, according to the Mine Safety and Health Administration, and these long-forgotten facilities can pose a variety of risks to people unaware of their presence. These risks aren't always visible ones.

Mine safety was thrust into recent headlines after Elizabeth Pollard, a 64-year-old grandmother, was swallowed up by a sinkhole in Unity Township, Pennsylvania, on Dec. 3. Pollard seemingly fell into the hole which led to an abandoned mining shaft, and her remains were found days later. Pennsylvania, like other Appalachian states, has many abandoned mines; there are at least two near the sinkhole where Pollard disappeared, according to the federal mining database.

While there are obvious safety risks associated with these old mines, experts are also sounding the alarm on environmental factors, as mines can greatly impact an area's water supply or even damage property. Unfortunately, shutting all of these mines down is easier said than done.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Why are these mines hazardous?

The subsidization of mines "has caused billions of dollars in damage in the U.S.," said The Associated Press. In Pennsylvania, there are at least "5,000 abandoned underground mines." Many more states, including others in Appalachia, plus Nevada and California, are also dotted with them.

As the general public does not know the exact location of these mines, they can easily create hazards. Many people have "died falling into [mines], and some murderers have tried to hide victims' bodies by dumping them in open mine shafts," said the AP. Even if a sinkhole isn't involved, people who wander into mines "can drown in flooded shafts, get lost in underground tunnels or perish from poisonous gases present in many old coal mines." Mine shafts "can extend hundreds of feet beneath the surface and often are unmarked."

Beyond the physical risks, mines will often impact the environment. Some "elevated levels of lithium, rubidium and cesium have been detected in waters associated with the historic Kings Mountain Mine" in North Carolina, said Newsweek. In these waters, it was found that "common regulated contaminants — including arsenic, lead, copper and nickel — were present at levels below drinking water and ecological standards."

Lead has also been discovered in mining sites both across the U.S. and internationally. The United Kingdom "has 6,630 abandoned lead mines that continue to disperse the metal into the environment each year," said the Financial Times. Food safety watchdogs are investigating these lead levels, which "can accumulate in waterways and soil before being consumed by animals and entering the food chain."

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Can anything be done to lessen the danger?

The best solution is to close off the mines — but that is a tall order, simply because there are so many. In the gold rush state of Colorado, about "13,500 mine features have been closed so far," said Marketplace, and the state can close down about 300 per year. But that is still only half of the total mines in Colorado. "In a state where mining was fundamental to its early economy, the quiet work of closing up these mines will likely go on for decades," the outlet said.

A "lack of federal funding can make cleanup difficult," said the Santa Fe New Mexican. Many areas also have wildlife living in their mines, which presents liabilities for endangered species. This can "make it challenging for the industry to pursue new projects and build trust with communities," Sid Smith, the government affairs manager for the American Exploration and Mining Association, said to the New Mexican. Even if mining companies "would like to clean up abandoned sites in an area, the liability hurdles make it challenging."

Justin Klawans has worked as a staff writer at The Week since 2022. He began his career covering local news before joining Newsweek as a breaking news reporter, where he wrote about politics, national and global affairs, business, crime, sports, film, television and other news. Justin has also freelanced for outlets including Collider and United Press International.

-

What to know before filing your own taxes for the first time

What to know before filing your own taxes for the first timethe explainer Tackle this financial milestone with confidence

-

The biggest box office flops of the 21st century

The biggest box office flops of the 21st centuryin depth Unnecessary remakes and turgid, expensive CGI-fests highlight this list of these most notorious box-office losers

-

The 10 most infamous abductions in modern history

The 10 most infamous abductions in modern historyin depth The taking of Savannah Guthrie’s mother, Nancy, is the latest in a long string of high-profile kidnappings

-

AI surgical tools might be injuring patients

AI surgical tools might be injuring patientsUnder the Radar More than 1,300 AI-assisted medical devices have FDA approval

-

How roadkill is a surprising boon to scientific research

How roadkill is a surprising boon to scientific researchUnder the radar We can learn from animals without trapping and capturing them

-

The world’s oldest rock art paints a picture of human migration

The world’s oldest rock art paints a picture of human migrationUnder the Radar The art is believed to be over 67,000 years old

-

Moon dust has earthly elements thanks to a magnetic bridge

Moon dust has earthly elements thanks to a magnetic bridgeUnder the radar The substances could help supply a lunar base

-

The ocean is getting more acidic — and harming sharks’ teeth

The ocean is getting more acidic — and harming sharks’ teethUnder the Radar ‘There is a corrosion effect on sharks’ teeth,’ the study’s author said

-

The Iberian Peninsula is rotating clockwise

The Iberian Peninsula is rotating clockwiseUnder the radar We won’t feel it in our lifetime

-

The ‘eclipse of the century’ is coming in 2027

The ‘eclipse of the century’ is coming in 2027Under the radar It will last for over 6 minutes

-

NASA discovered ‘resilient’ microbes in its cleanrooms

NASA discovered ‘resilient’ microbes in its cleanroomsUnder the radar The bacteria could contaminate space