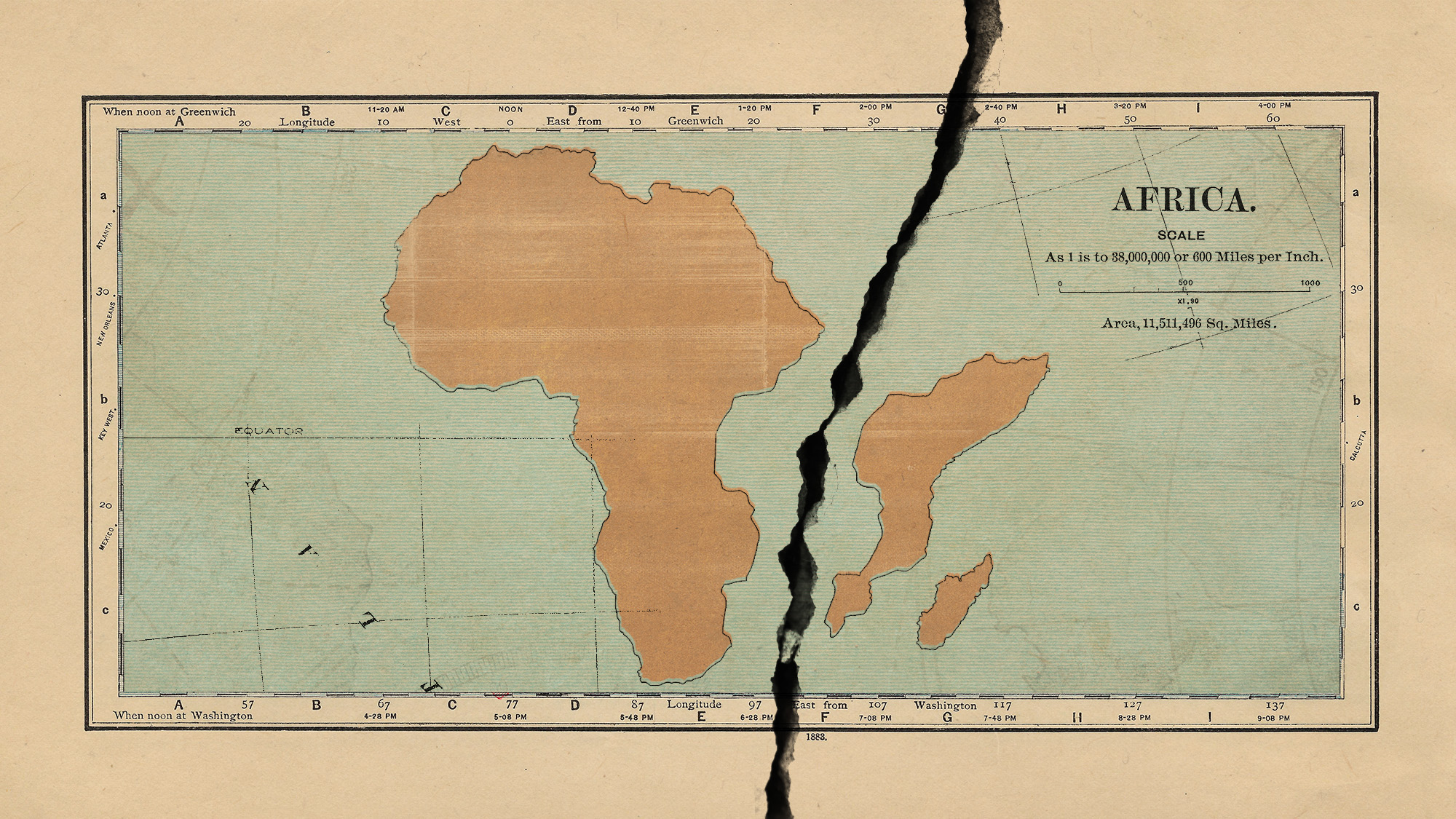

Africa is going through a massive breakup thanks to an impending continental separation

The continent is splitting in two, though it will not happen in our lifetimes

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Africa is dividing in two, and a new landmass and ocean may form sooner than expected. The change could alter the climate and ecosystem of the region, as well as the way humans live. In the geologic history of Earth, shifting plate tectonics are commonplace, and Africa's impending rift is but another chapter in that story.

The cracks are showing

The Earth's continents are far from constant. Plate tectonics have caused the landmasses to shift over time, and another shift is occurring in the 21st century.

Scientists have known for the past two decades that Africa has been splitting. In 2005, Ethiopia experienced earthquakes that caused the appearance of a 35-mile-long fissure in the desert called the East African Rift. "It marked the start of a long process in which the African plate is splitting into two tectonic plates: the Somali plate and the Nubian plate," said Unilad. Then, in 2018, another crack appeared in Kenya along the rift.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The cracks are "associated with the East African Rift System (EARS)," which stretches "downward for thousands of kilometers through several countries in Africa, including Ethiopia, Kenya, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Uganda, Rwanda, Burundi, Zambia, Tanzania, Malawi and Mozambique," said IFL Science. The rift has been widening over time, and along the system there have been varying levels of seismic activity, according to a study published in the journal Frontiers in Earth Science. But "in the human life scale, you won't be seeing many changes," Ken Macdonald, a professor at the University of California, Santa Barbara, said to Daily Mail. "You'll be feeling earthquakes, you'll be seeing volcanoes erupt, but you won't see the ocean intrude in our lifetimes."

Even with the long timelines, scientists suggest that the rift is happening quicker than previously thought. Original estimates put a complete split at tens of millions of years from now. "With the continent dividing at a rate of half an inch per year, those estimations have sped up," said Unilad. MacDonald puts the timeline at between one million and five million years.

A whole new world

The split will change the world's continental makeup. "Somalia, Kenya, Tanzania and some parts of Ethiopia would form a new continent separated by the world's sixth ocean," said Metro. A change this drastic could have major implications for the region's biodiversity and ecosystem. Landlocked nations like Uganda and Zambia would gain coastlines, which could influence weather patterns and climate. "This transformation could affect biodiversity, water resources and agricultural practices, posing both challenges and opportunities for the inhabitants of East Africa," said HowStuffWorks. In addition, "the gradual separation might influence the continent's geopolitical landscape" and "create new opportunities for trade and communication."

A new continent is small potatoes in the context of Earth's geological history. All the continents were once a giant landmass known as Pangea, which then split off into the continents we know today. Only recently, scientists mapped the hidden continent of Zealandia located in the Southern Ocean. Africa's split "will be just another move in this giant geological playbook," said IFL Science. "Whether we as a species will survive for long enough to witness it? Well, that's a different story."

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Devika Rao has worked as a staff writer at The Week since 2022, covering science, the environment, climate and business. She previously worked as a policy associate for a nonprofit organization advocating for environmental action from a business perspective.

-

Nuuk becomes ground zero for Greenland’s diplomatic straits

Nuuk becomes ground zero for Greenland’s diplomatic straitsIN THE SPOTLIGHT A flurry of new consular activity in the remote Danish protectorate shows how important Greenland has become to Europeans’ anxiety about American imperialism

-

‘This is something that happens all too often’

‘This is something that happens all too often’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

House votes to end Trump’s Canada tariffs

House votes to end Trump’s Canada tariffsSpeed Read Six Republicans joined with Democrats to repeal the president’s tariffs

-

How roadkill is a surprising boon to scientific research

How roadkill is a surprising boon to scientific researchUnder the radar We can learn from animals without trapping and capturing them

-

NASA’s lunar rocket is surrounded by safety concerns

NASA’s lunar rocket is surrounded by safety concernsThe Explainer The agency hopes to launch a new mission to the moon in the coming months

-

The world’s oldest rock art paints a picture of human migration

The world’s oldest rock art paints a picture of human migrationUnder the Radar The art is believed to be over 67,000 years old

-

Moon dust has earthly elements thanks to a magnetic bridge

Moon dust has earthly elements thanks to a magnetic bridgeUnder the radar The substances could help supply a lunar base

-

The ocean is getting more acidic — and harming sharks’ teeth

The ocean is getting more acidic — and harming sharks’ teethUnder the Radar ‘There is a corrosion effect on sharks’ teeth,’ the study’s author said

-

Cows can use tools, scientists report

Cows can use tools, scientists reportSpeed Read The discovery builds on Jane Goodall’s research from the 1960s

-

The Iberian Peninsula is rotating clockwise

The Iberian Peninsula is rotating clockwiseUnder the radar We won’t feel it in our lifetime

-

The ‘eclipse of the century’ is coming in 2027

The ‘eclipse of the century’ is coming in 2027Under the radar It will last for over 6 minutes