Some of Earth's oldest crust is disintegrating. No cause for alarm, folks.

Even the most stable land is slowly changing

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

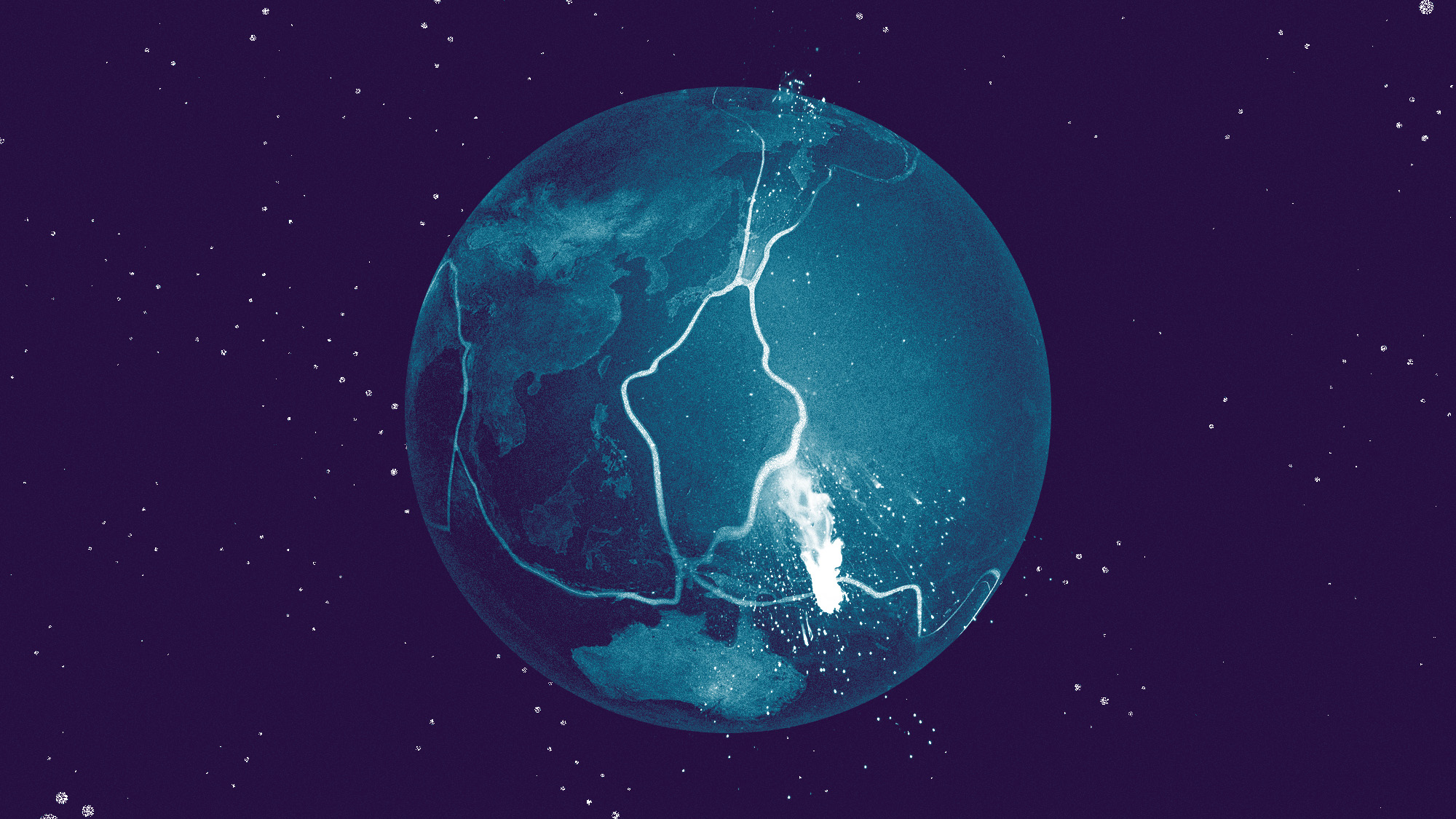

Stable parts of the Earth's crust may not be as immovable as previously thought. While much of the crust is affected by plate tectonic activity, certain more stable portions have remained unchanged for a long time. But new research suggests that even the oldest crust is disintegrating due to natural processes and these erosions could eventually alter the surface of the Earth.

Craton crumbles

Earth's crust, or the outermost shell of the planet, has drastically changed throughout geologic history, mostly due to the work of plate tectonics. Over time, the crust's topography and position, including the location of continents, has not been fixed even though it seems that way in the present era.

The planet has "more stable formations of rock," called cratons, which "contain old 'roots' … from which tectonic plates extend," said Popular Mechanics. These cratons have had long-term stability and have remained largely unchanged for millions of years. Recently, a study published in the journal Nature Geoscience found that some of the world's oldest cratons are breaking apart.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The disintegration happens in a process called decratonization. Though the cause of decratonization is unclear, scientists posit that subduction, "when a denser tectonic plate is forced beneath the other into the underlying mantle where it melts," and deep mantle plumes, "when a segment of the mantle rises to the surface due to its buoyancy and thermally erodes the crust," could be possible causes, said Phys.org.

The study examined the changes to the North China Craton (NCC) over 200 million years. Scientists observed subduction as well as a process known as flat-slab rollback, which is "when the subducting plate retreats back to the surface." The processes led to the lithosphere, which consists of the Earth's crust and upper mantle, thinning and extending seaward.

Altering crusts

The NCC was specifically studied, but "the North American craton, South American craton and the Yangtze craton in China may have experienced similar deformation," Shaofeng Liu, the lead author of the study, said to Phys.org. "All of these may have experienced early flat-slab subduction." Additional changes varied across the cratons. "Intense subsequent rollback subduction might have occurred in the Yangtze craton. In contrast, the North American craton underwent trench retreat following flat-slab subduction but did not exhibit significant slab rollback."

The changing of Earth's crust is a topic that is still being studied. Plate tectonics as they are currently known likely occurred during the past billion years, according to a 2021 study. The same study also found that Earth's crust plates "get weak and bendy, like a slinky snake toy, but they don't disintegrate completely," when they slide past each other, said LiveScience.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

These movements have been instrumental in positioning the landmasses the way they exist now. Understanding how the crust changes can give insight into how the planet may look in the future. "Ancient lithosphere can be broken apart, and this disintegration can be caused by this special form of subduction occurring near oceanic plates, revealing how the continents evolved over Earth's history," said Liu. Substantive changes are still hundreds of millions of years away.

Devika Rao has worked as a staff writer at The Week since 2022, covering science, the environment, climate and business. She previously worked as a policy associate for a nonprofit organization advocating for environmental action from a business perspective.

-

Democrats push for ICE accountability

Democrats push for ICE accountabilityFeature U.S. citizens shot and violently detained by immigration agents testify at Capitol Hill hearing

-

The price of sporting glory

The price of sporting gloryFeature The Milan-Cortina Winter Olympics kicked off this week. Will Italy regret playing host?

-

Fulton County: A dress rehearsal for election theft?

Fulton County: A dress rehearsal for election theft?Feature Director of National Intelligence Tulsi Gabbard is Trump's de facto ‘voter fraud’ czar

-

How roadkill is a surprising boon to scientific research

How roadkill is a surprising boon to scientific researchUnder the radar We can learn from animals without trapping and capturing them

-

NASA’s lunar rocket is surrounded by safety concerns

NASA’s lunar rocket is surrounded by safety concernsThe Explainer The agency hopes to launch a new mission to the moon in the coming months

-

The world’s oldest rock art paints a picture of human migration

The world’s oldest rock art paints a picture of human migrationUnder the Radar The art is believed to be over 67,000 years old

-

Moon dust has earthly elements thanks to a magnetic bridge

Moon dust has earthly elements thanks to a magnetic bridgeUnder the radar The substances could help supply a lunar base

-

The ocean is getting more acidic — and harming sharks’ teeth

The ocean is getting more acidic — and harming sharks’ teethUnder the Radar ‘There is a corrosion effect on sharks’ teeth,’ the study’s author said

-

How Mars influences Earth’s climate

How Mars influences Earth’s climateThe explainer A pull in the right direction

-

Cows can use tools, scientists report

Cows can use tools, scientists reportSpeed Read The discovery builds on Jane Goodall’s research from the 1960s

-

The Iberian Peninsula is rotating clockwise

The Iberian Peninsula is rotating clockwiseUnder the radar We won’t feel it in our lifetime