The first moon lander launch in decades almost didn't happen

5, 4, 3, 2 … drama

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The U.S. recently launched what would have been its first commercial lunar lander since 1972, a flight that nearly stopped before it started. After a successful launch in January, the Peregrine lander was set to land on the moon's surface in February 2024. Part of the plan was for the rocket to deposit some human remains on the moon after landing. This sparked sufficient backlash to nearly ground Peregrine for good.

What was the goal?

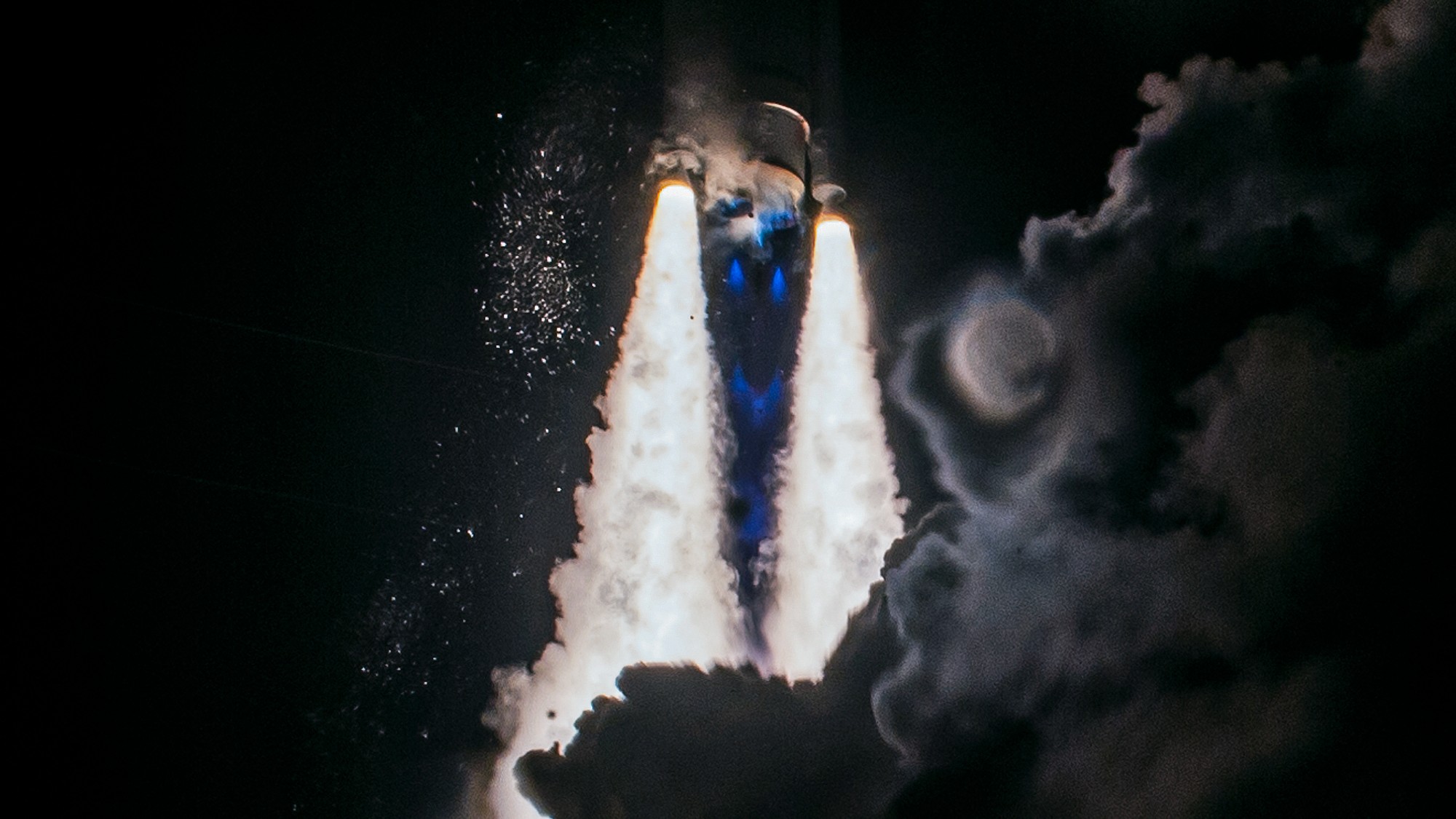

Multiple nations have their sights set on implementing a base on the moon in a new era space race, which could be instrumental in claiming resources and setting up communications. As such, NASA funded the private company Astrobotic Technology, along with another company, Intuitive Machines, to develop lunar landers that would deliver technology to the moon. These landers would also make private deliveries before astronauts are sent spaceward. Astrobotic's lander, Peregrine, was launched into space on January 8, 2024, using a new rocket called the Vulcan Centaur. (Intuitive Machines' lander is expected to launch next month using a rocket developed by SpaceX.)

Private landers are instrumental in aiding NASA's Artemis project, which aims to put humans back on the moon and establish a long-term presence there. Peregrine was equipped with data collection gear to relay information about the moon's surface back to NASA. In addition, the lander was aiming to land at the mid-latitudes of the moon while carrying five payloads to be deposited. The payloads contained NASA equipment, as well as items and materials from private companies. "American companies bringing equipment and cargo and payloads to the moon is a totally new industry," NASA deputy associate administrator for exploration Joel Kearns said in a press call.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

What was the concern?

Part of the Peregrine's payloads included material from two space-burial companies, Celestis and Elysium, which, according to NPR, "allow people to pay to send their loved ones' cremated remains into the cosmos on what are called 'memorial spaceflights.'" The lander was set to deposit the remains of almost 70 people, including George Washington and John F. Kennedy, on the moon. This was a problem for the Navajo Nation. "The moon holds a sacred place in Navajo cosmology," Buu Nygren, president of the Navajo Nation, wrote in a statement. "The suggestion of transforming it into a resting place for human remains is deeply disturbing and unacceptable to our people and many other tribal nations."

Officials from the White House and NASA met with Nygren to discuss the objections from the Navajo Nation, one of the largest of the U.S.'s Indigenous groups. "We really are trying to do the right thing," John Thornton, the chief executive of Astrobotic, told The New York Times. "I hope we can find a good path forward with the Navajo Nation." Both the government and companies sending the remains to space decided the Navajo Nation's concerns weren't "substantive," Celestis CEO Charles Chafer told CNN, and the launch happened as planned.

Following the meeting, Nygren remarked, "They're not going to remove the human remains and keep them here on Earth where they were created, but instead, we were just told that a mistake has happened," and in the future, they're "going to try to consult with [us]." Kearns, NASA deputy associate administrator for exploration, added, "Those communities may not understand that these missions are commercial, and they're not U.S. government missions." In a rocket-powered bit of irony, the contested remains are not likely to make it to the moon anyhow. The spacecraft suffered a critical propellant loss from a fuel leak, precluding Peregrine from sticking its lunar landing.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Devika Rao has worked as a staff writer at The Week since 2022, covering science, the environment, climate and business. She previously worked as a policy associate for a nonprofit organization advocating for environmental action from a business perspective.

-

The ‘ravenous’ demand for Cornish minerals

The ‘ravenous’ demand for Cornish mineralsUnder the Radar Growing need for critical minerals to power tech has intensified ‘appetite’ for lithium, which could be a ‘huge boon’ for local economy

-

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?IN THE SPOTLIGHT As the president muses about polling place deployments and a centralized electoral system aimed at one-party control, lawmakers are taking this administration at its word

-

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

NASA’s lunar rocket is surrounded by safety concerns

NASA’s lunar rocket is surrounded by safety concernsThe Explainer The agency hopes to launch a new mission to the moon in the coming months

-

Nasa’s new dark matter map

Nasa’s new dark matter mapUnder the Radar High-resolution images may help scientists understand the ‘gravitational scaffolding into which everything else falls and is built into galaxies’

-

Moon dust has earthly elements thanks to a magnetic bridge

Moon dust has earthly elements thanks to a magnetic bridgeUnder the radar The substances could help supply a lunar base

-

How Mars influences Earth’s climate

How Mars influences Earth’s climateThe explainer A pull in the right direction

-

The ‘eclipse of the century’ is coming in 2027

The ‘eclipse of the century’ is coming in 2027Under the radar It will last for over 6 minutes

-

NASA discovered ‘resilient’ microbes in its cleanrooms

NASA discovered ‘resilient’ microbes in its cleanroomsUnder the radar The bacteria could contaminate space

-

Artemis II: back to the Moon

Artemis II: back to the MoonThe Explainer Four astronauts will soon be blasting off into deep space – the first to do so in half a century

-

The mysterious origin of a lemon-shaped exoplanet

The mysterious origin of a lemon-shaped exoplanetUnder the radar It may be made from a former star