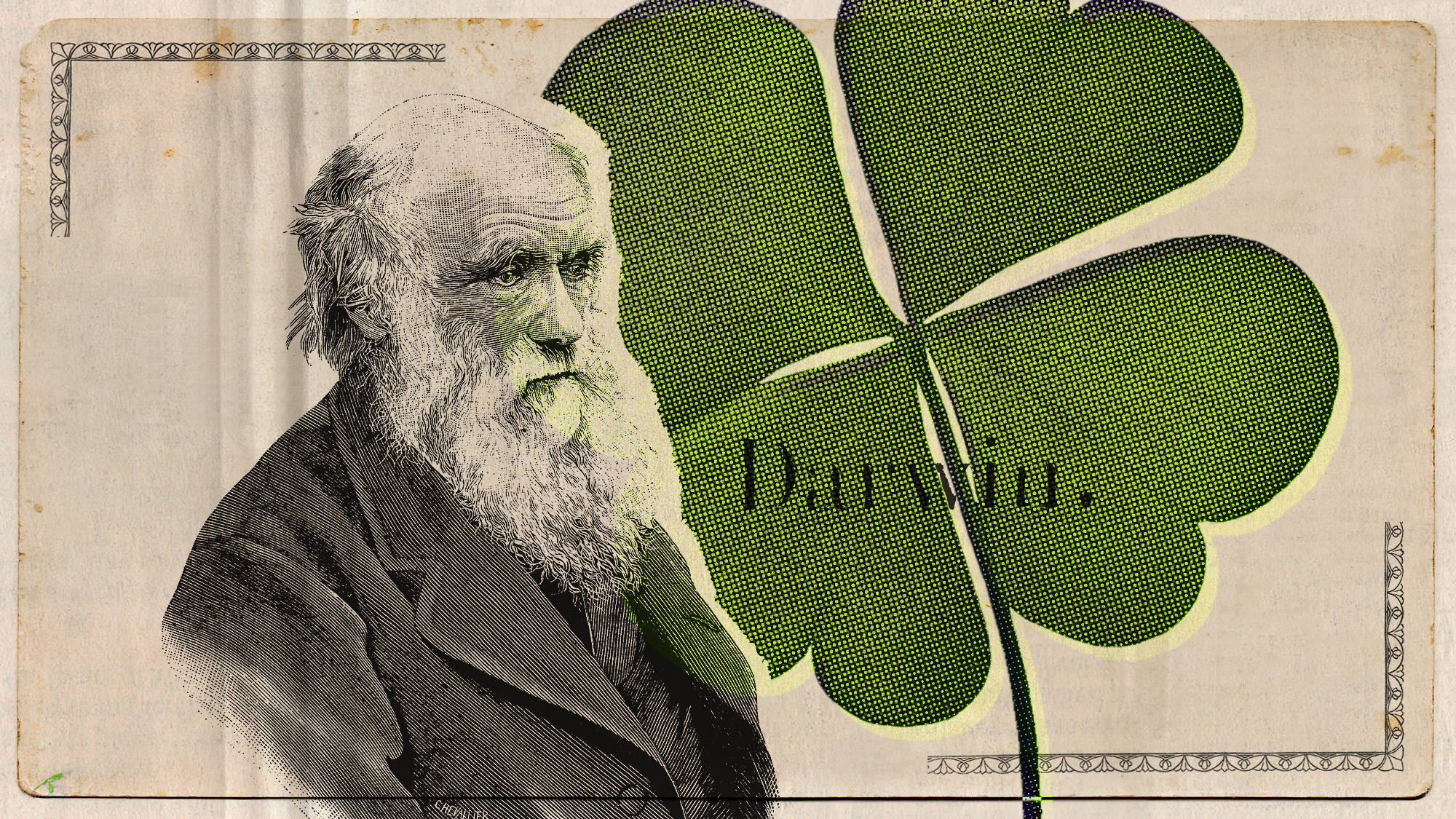

Luck be an evolutionary lady tonight

Evolutionary change is sometimes as simply and unpredictable as a roll of the dice

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Evolution has been known as survival of the fittest, however the fittest may also have been simply the luckiest. Though genetics are a driving force of evolution, many evolutionary changes were a result of random occurrences or being at the right place at the right time.

Survival of the luckiest

Species evolve when "individuals who are better adapted to their environment — those that manage to acquire food, escape predators, survive diseases and parasites and attract successful partners — are the ones to reproduce and pass on their traits to the next generation," said the Davidson Institute of Science Education. Many traits originally came in the form of a random genetic mutation. "Each genetic change that contributed to these traits originally appeared by chance in one individual in the population and spread through the population by helping that individual reproduce."

While this process was common knowledge, luck can also affect individuals that are identical in genes and circumstances. An article published in the journal Science found that contingent events, also known as luck, can play a significant part in developmental trajectories, especially when it comes to competition. "A male ram battling for a female's attention might face a rival that accidentally slips on a loose rock and tumbles to its death," said NPR. "A foraging bird may happen upon a bonanza of food before others, just by chance."

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

To test this, researchers created an equal society of mice. "Groups of about 26 two-week-old mice and their mothers were placed in outdoor enclosures in groups that mimicked their natural environment but had identical 'resource zones' with food and shelter," said NPR. This species of mouse had males competing for resources, and females were not. Luck affected the males far more than females. "An individual male mouse might just so happen to win a fight with its identical twin over food. That lucky break would help it become bigger than its twin, setting it up to win the next fight."

The males "pretty early on start to diverge into really high quality and low quality males, or males that are gaining access to resources and males that are being excluded from resources," Michael Sheehan, a biologist at Cornell University and senior author of the study, said to NPR. "We don't see that pattern pan out for the females. They all kind of stay about the same quality the whole time."

An unequal distribution

Genetics and circumstances go hand in hand when it comes to evolution. "Everywhere we look, outcomes across populations are unequal," Matthew Zipple, an evolutionary biologist at Cornell University and study author, said to NPR. Even "probability and chance play a significant role in the fate of a particular gene," said the Davidson Institute. Just because a favorable gene emerges in a population does not necessarily mean it will be passed on.

This idea gave rise to the neutral theory, which is the "historically controversial idea that 'survival of the fittest' isn't the only, or even the most common, way that species change, split or disappear," said The Atlantic. Instead, the theory placed luck as one of the most significant factors in evolution. "What we're finding is that even if you have something special about you, something that's lasting — you're particularly vigorous or have great genes — that is a necessary but not sufficient trait to be exceptionally successful," Robin Snyder, a theoretical ecologist at Case Western Reserve University, said to NPR. "You also have to be lucky."

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Devika Rao has worked as a staff writer at The Week since 2022, covering science, the environment, climate and business. She previously worked as a policy associate for a nonprofit organization advocating for environmental action from a business perspective.

-

Political cartoons for February 15

Political cartoons for February 15Cartoons Sunday's political cartoons include political ventriloquism, Europe in the middle, and more

-

The broken water companies failing England and Wales

The broken water companies failing England and WalesExplainer With rising bills, deteriorating river health and a lack of investment, regulators face an uphill battle to stabilise the industry

-

A thrilling foodie city in northern Japan

A thrilling foodie city in northern JapanThe Week Recommends The food scene here is ‘unspoilt’ and ‘fun’

-

AI surgical tools might be injuring patients

AI surgical tools might be injuring patientsUnder the Radar More than 1,300 AI-assisted medical devices have FDA approval

-

How roadkill is a surprising boon to scientific research

How roadkill is a surprising boon to scientific researchUnder the radar We can learn from animals without trapping and capturing them

-

NASA’s lunar rocket is surrounded by safety concerns

NASA’s lunar rocket is surrounded by safety concernsThe Explainer The agency hopes to launch a new mission to the moon in the coming months

-

The world’s oldest rock art paints a picture of human migration

The world’s oldest rock art paints a picture of human migrationUnder the Radar The art is believed to be over 67,000 years old

-

Moon dust has earthly elements thanks to a magnetic bridge

Moon dust has earthly elements thanks to a magnetic bridgeUnder the radar The substances could help supply a lunar base

-

The ocean is getting more acidic — and harming sharks’ teeth

The ocean is getting more acidic — and harming sharks’ teethUnder the Radar ‘There is a corrosion effect on sharks’ teeth,’ the study’s author said

-

Cows can use tools, scientists report

Cows can use tools, scientists reportSpeed Read The discovery builds on Jane Goodall’s research from the 1960s

-

The Iberian Peninsula is rotating clockwise

The Iberian Peninsula is rotating clockwiseUnder the radar We won’t feel it in our lifetime