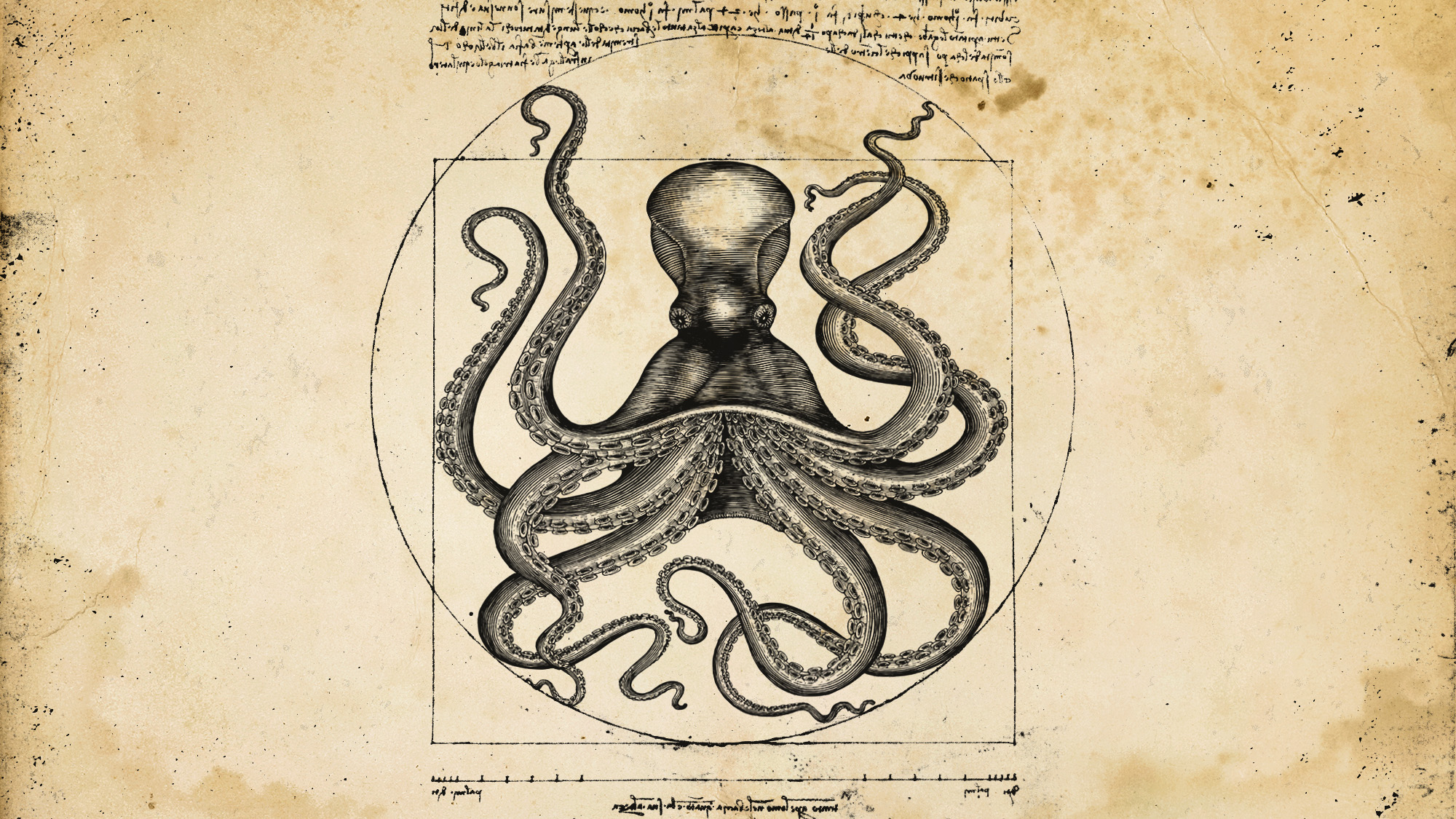

Octopuses could be the next big species after humans

What has eight arms, a beaked mouth, and is poised to take over the planet when we're all gone?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Last year, speculative fiction author Ray Nayler published "The Mountain in the Sea," his first novel, depicting a not-too-distant future in which humankind is faced with an awe-inspiring (and deeply disquieting) possibility: that our singular perch atop the evolutionary ladder may not be quite so singular after all. In the novel, a newly discovered community of hyper-intelligent octopuses off the coast of Vietnam developed its own advanced language and the ability to use complex tools.

While Nayler's story is wholly fictional, it is not without basis in a very real school of zoological thought, one which holds that octopuses are indeed unique within the animal kingdom as we understand it today. So much so that they may be Earth's next big species if ours ends up going the way of the dinosaurs.

'Filling an ecological niche in a post-human world'

While an octopus-dominated future may seem "improbable" at the moment, it "wouldn’t be the first time that an ocean-dwelling species took advantage of a land species extinction to adapt and evolve," Popular Mechanics said. That would namely be us humans, whose distant ancestors were initially aquatic before becoming land-based mammals.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Although birds and insects have demonstrated a capacity for complex thinking and tool usage, it's octopuses that are a "potentially better candidate for filling an ecological niche in a post-human world," Oxford University biologist Tim Coulson said to The European. They are some of the "most intelligent, adaptable and resourceful creatures on Earth," and octopuses' "advanced neural structure, decentralized nervous system and remarkable problem-solving skills" make certain types "well suited for an unpredictable world" under the right circumstances. They are even "capable of distinguishing between real and virtual objects, solving puzzles, interacting with their environment, handling intricate tools with their thumb-like tentacles, and thriving in a wide variety of habitats."

'Not likely to develop a culture'

Octopuses have certain biological features that could, under the right circumstances, place them at the top of the evolutionary heap, but there are a lot of variables involved that could waylay any hopes of an octo-centric future. Absent some dramatic, unforeseen evolutionary leap, "octopuses are still working from a snail blueprint, and there's only so much you can do with that toolbox," said biologist Culum Brown of Australia's Macquarie University at The Conversation. Crucially, octopuses' evolutionary prospects are "highly constrained by their very short life span," with most living for "just a year and some as little as six months."

Dexterity and problem-solving skills aside, octopuses are unlikely to create a "human-like society because of their social habits," said University of Sydney Philosophy of Science Professor Peter Godfrey-Smith to Popular Mechanics. In large part, that's because octopus parents are virtually non-existent in their babies' lives, meaning that in order to develop anything resembling a "culture" as we understand it, they would need to evolve to foster "more intergenerational connections." Given that octopuses have been evolving for hundreds of millions of years without those sorts of multi-generational cultural advantages, it's "unlikely that this will change anytime soon," the magazine said.

Conversely, however, octopuses' "hasty reproduction and quick intellectual maturity" could give them an "advantage in rapidly changing environments, thereby accelerating their evolutionary progress," Earth.com said. "These are just possibilities," Coulson said to The European. "It's impossible to predict with any degree of certainty how evolution will unfold over extended periods."

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Rafi Schwartz has worked as a politics writer at The Week since 2022, where he covers elections, Congress and the White House. He was previously a contributing writer with Mic focusing largely on politics, a senior writer with Splinter News, a staff writer for Fusion's news lab, and the managing editor of Heeb Magazine, a Jewish life and culture publication. Rafi's work has appeared in Rolling Stone, GOOD and The Forward, among others.

-

Colbert, CBS spar over FCC and Talarico interview

Colbert, CBS spar over FCC and Talarico interviewSpeed Read The late night host said CBS pulled his interview with Democratic Texas state representative James Talarico over new FCC rules about political interviews

-

The Week contest: AI bellyaching

The Week contest: AI bellyachingPuzzles and Quizzes

-

Political cartoons for February 18

Political cartoons for February 18Cartoons Wednesday’s political cartoons include the DOW, human replacement, and more

-

AI surgical tools might be injuring patients

AI surgical tools might be injuring patientsUnder the Radar More than 1,300 AI-assisted medical devices have FDA approval

-

How roadkill is a surprising boon to scientific research

How roadkill is a surprising boon to scientific researchUnder the radar We can learn from animals without trapping and capturing them

-

NASA’s lunar rocket is surrounded by safety concerns

NASA’s lunar rocket is surrounded by safety concernsThe Explainer The agency hopes to launch a new mission to the moon in the coming months

-

The world’s oldest rock art paints a picture of human migration

The world’s oldest rock art paints a picture of human migrationUnder the Radar The art is believed to be over 67,000 years old

-

Moon dust has earthly elements thanks to a magnetic bridge

Moon dust has earthly elements thanks to a magnetic bridgeUnder the radar The substances could help supply a lunar base

-

The ocean is getting more acidic — and harming sharks’ teeth

The ocean is getting more acidic — and harming sharks’ teethUnder the Radar ‘There is a corrosion effect on sharks’ teeth,’ the study’s author said

-

Cows can use tools, scientists report

Cows can use tools, scientists reportSpeed Read The discovery builds on Jane Goodall’s research from the 1960s

-

The Iberian Peninsula is rotating clockwise

The Iberian Peninsula is rotating clockwiseUnder the radar We won’t feel it in our lifetime