What is the Anthropocene — and more importantly, when?

Just because a panel of scientists has rejected calls to classify a new global epoch does not mean it hasn't already begun

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

There is no question that the existence of humans as a species has dramatically altered planet Earth in ways both obvious and subtle. From the air we breathe to the ground we walk on to the water we drink, our world has undergone (and continues to undergo) changes. These changes are so enormous, that their impact on if and how life on this planet moves forward remains hard to fully grasp — even as their broad effects are already beginning to be felt.

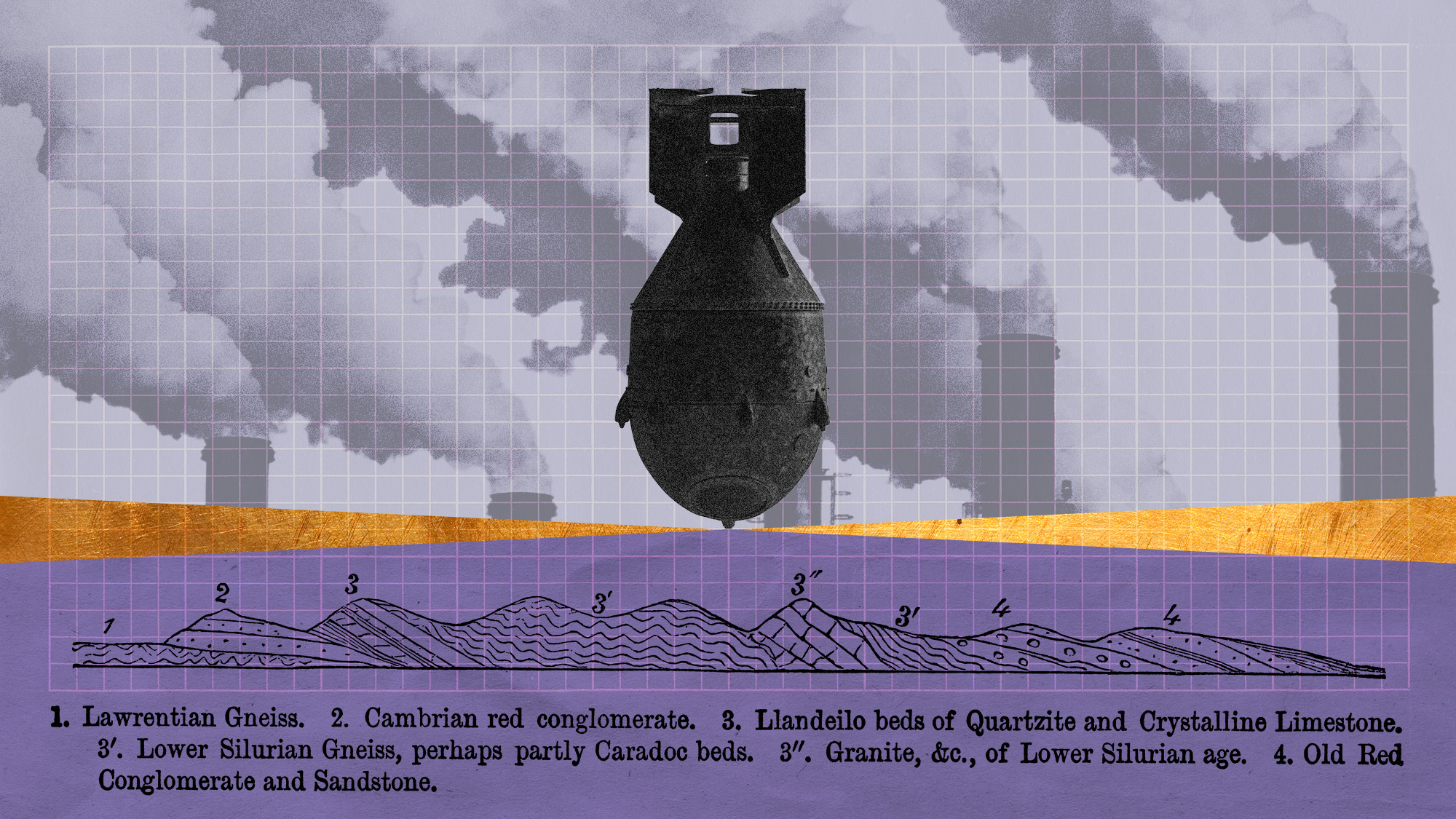

But although it is undeniable that humanity has made its environmental presence felt, scientists have struggled to encapsulate what that entails in geological terms, though not for lack of trying. For the past 15 years, researchers with the Anthropocene Working Group (AWG) have argued that the epoch of human-driven changes to the Earth's geology (for which their team is named) began more than a half-century ago with the advent of the atomic bomb and its ensuing radiological fallout. Last week that debate ended — temporarily at least — with a ruling from the International Commission on Stratigraphy (ICS) that rejected calls to declare the official state of the Anthropocene and the end of the Holocene epoch that has defined the planet's past 11,700 years.

While on one hand this may seem like a niche scientific conflict over terminology, the arguments for and against naming this the Anthropocene have proven to be about way more than mere semantics.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

"Our still-unfolding present"

Abstract as the debate over the naming of our current geologic epoch may seem, there are some concrete implications that come with opting to (or in this case, opting not to) officially designate a new era; doing so would "shape terminology in textbooks, research articles and museums worldwide," said The New York Times, which broke news of the ICS's decision. Perhaps more importantly, it would "guide scientists in their understanding of our still-unfolding present for generations, perhaps even millenniums, to come."

In part, the disagreement centered not on whether the Anthropocene exists at all, but rather when it began and what, ultimately, it is. While some have argued it should be an epoch akin to the Holocene, others have classified it as "an 'event,' like a mass extinction," the BBC said. Moreover, while the AWC pegged the mid-20th century as the official start of the Anthropocene — a "golden spike" moment in geological terminology, named for the physical tine used to indicate the epoch's start in various rock formations — some experts have suggested other potential starting points. These include rising methane levels from early farms, metal pollution from mining, and the environmental fallout from the Industrial Revolution.

The AWC's proposed Anthropocene timeline is "no more than 75 years — a single human lifetime," University of Wales Earth Sciences Professor Mike Walker said to New Scientist. That comparatively short time frame does not "fit comfortably into the geological time scale, where units typically span thousands, tens of thousands or millions of years." Former AWC member Erle Ellis, a professor of Geography and Environmental Systems at the University of Maryland, agreed: By so explicitly tying the Anthropocene to the mid-20th century, his former colleagues "risked sowing confusion about the deep history of how humans are transforming the Earth," he said for The Conversation.

But the vote to officially reject this narrow classification of the Anthropocene, Ellis stressed, has "no bearing on the overwhelming evidence" that our species is "indeed transforming this planet."

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

"Here to stay"

The ICS's rejection is currently being challenged for "procedural irregularities," one of the committee members told Nature. The group is alleging that the vote had been "performed in contravention of the statutes of the International Commission on Stratigraphy."

If their appeal fails, the group will have to wait a decade before resubmitting their proposal thanks to a "mandatory cooling-off period" instituted by the ICS "given how furious debates can turn," Science said. Regardless of official designation, the Anthropocene is "here to stay," with the term already in use in "art exhibits, journal titles and endless books."

Even if their appeal fails, the scientific work done by the AWG is "excellent," ICS Secretary General Philip Gibbard, a University of Cambridge geologist who voted against the proposal, said to The Washington Post. "It’s not to be wasted. It’s just to be used differently, that’s all."

Rafi Schwartz has worked as a politics writer at The Week since 2022, where he covers elections, Congress and the White House. He was previously a contributing writer with Mic focusing largely on politics, a senior writer with Splinter News, a staff writer for Fusion's news lab, and the managing editor of Heeb Magazine, a Jewish life and culture publication. Rafi's work has appeared in Rolling Stone, GOOD and The Forward, among others.