The science behind nuclear weapons

What makes them so deadly?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Ongoing global conflict has pushed the notion of nuclear warfare back to the forefront of the world's collective mind. While there have been other threats of potential nuclear attacks, the bombs have only ever been used twice in history, dropped in Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The resulting blast killed hundreds of thousands of civilians. But what makes them so deadly?

What is a nuclear weapon?

The Centers for Disease Control defines a nuclear weapon as a "device that uses a nuclear reaction to create an explosion." When exploded it releases four types of energy, "a blast wave, intense light, heat, and radiation." The impact of detonation is monumental, causing far more substantial damage than standard missiles or bombs. The high levels of radiation emitted from the weapons are what pose the largest threat.

Nuclear weapons can cause widespread death and injury along with blindness, radiation sickness, and the effects of nuclear fallout, which is made up of "dust-like particles" that fall to the earth following the initial blast and contaminate the area. The blast can impact those quite far out of the radius of the explosion because of fallout. According to the MIT Press Reader, "fallout contamination may linger for years and even decades, the dominant lethal effects last from days to weeks."

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

"The ultimate goal is to never use these things," said Mark Herrmann at the nuclear research center Lawrence Livermore.

How do nuclear weapons work?

It all starts with atoms, which make up all matter. Each atom has a nucleus which is made up of positively charged protons and neutral neutrons. Every element has a distinct number of protons, however, the number of neutrons in the nucleus can vary. The variations are known as isotopes. Some isotopes are unstable, which makes them radioactive. Isotopes become unstable if the ratio of protons to neutrons in the nucleus is too large for some elements.

The destructive power of the weapons comes from two processes: nuclear fission, when "scientists split the nucleus of an atom into two smaller fragments with a neutron," and nuclear fusion, which "involves bringing together two smaller atoms to form a larger one."

In nuclear fission, neutrons collide with the nucleus of an unstable isotope, namely uranium-235 or plutonium-239, which in turn forces the atom into "splitting the nucleus into fragments and releasing a tremendous amount of energy," according to the Atomic Heritage Foundation. The process "becomes self-sustaining as neutrons produced by the splitting of atom strike nearby nuclei and produce more fission."

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Fusion bombs are more efficient than fission bombs alone. "When exposed to extremely high temperatures and pressures, some lightweight nuclei can fuse together to form heavier nuclei," and in turn release energy, as described by the Union of Concerned Scientists. However, in order to spark the fusion reaction, modern-day weapons tend to have a preliminary fission reaction, giving them a "two-stage design — a primary fission or boosted-fission component and a secondary fusion component."

Using weapons with both reactions "can release more explosive energy in a fraction of a second than all of the weapons used during World War II combined," including the two nuclear bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, as the Union of Concerned Scientists explained.

What would nuclear war look like?

With ongoing global tension, especially among the U.S., China, Russia, and North Korea, the fear of nuclear threats has remained top-of-mind.

The strength and intensity of modern nuclear weapons are far greater than the ones used during World War II, with the potential to cause "global fallout" because of the "sheer quantity of radioactive material and partly from the fact that the radioactive cloud rises well into the stratosphere, where it may take months or even years to reach the ground," according to MIT Press Reader. The number of direct injuries would also be substantial and "a single nuclear explosion might produce 10,000 cases of severe burns requiring specialized medical treatment; in an all-out war there could be several million such cases."

In theory, if one nation were to use a nuclear weapon, the target country would likely retaliate with a nuclear attack as well, which could lead to what is called a nuclear winter, which is when "smoke from the fires started by nuclear weapons ... would be heated by the Sun, lofted into the upper stratosphere, and spread globally, lasting for years." In turn, it would create cold and dark conditions which would prevent crop growth and threaten human survival.

"There is an urgent need for public education within all nuclear-armed states that is informed by the latest research," remarked Paul Ingram, senior research associate at the University of Cambridge's Centre for the Study of Existential Risk. "We need to collectively reduce the temptation that leaders of nuclear-armed states might have to threaten or even use such weapons in support of military operations."

Devika Rao has worked as a staff writer at The Week since 2022, covering science, the environment, climate and business. She previously worked as a policy associate for a nonprofit organization advocating for environmental action from a business perspective.

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?Today’s Big Question Democrats want to rein in ICE’s immigration crackdown

-

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

Why scientists are attempting nuclear fusion

Why scientists are attempting nuclear fusionThe Explainer Harnessing the reaction that powers the stars could offer a potentially unlimited source of carbon-free energy, and the race is hotting up

-

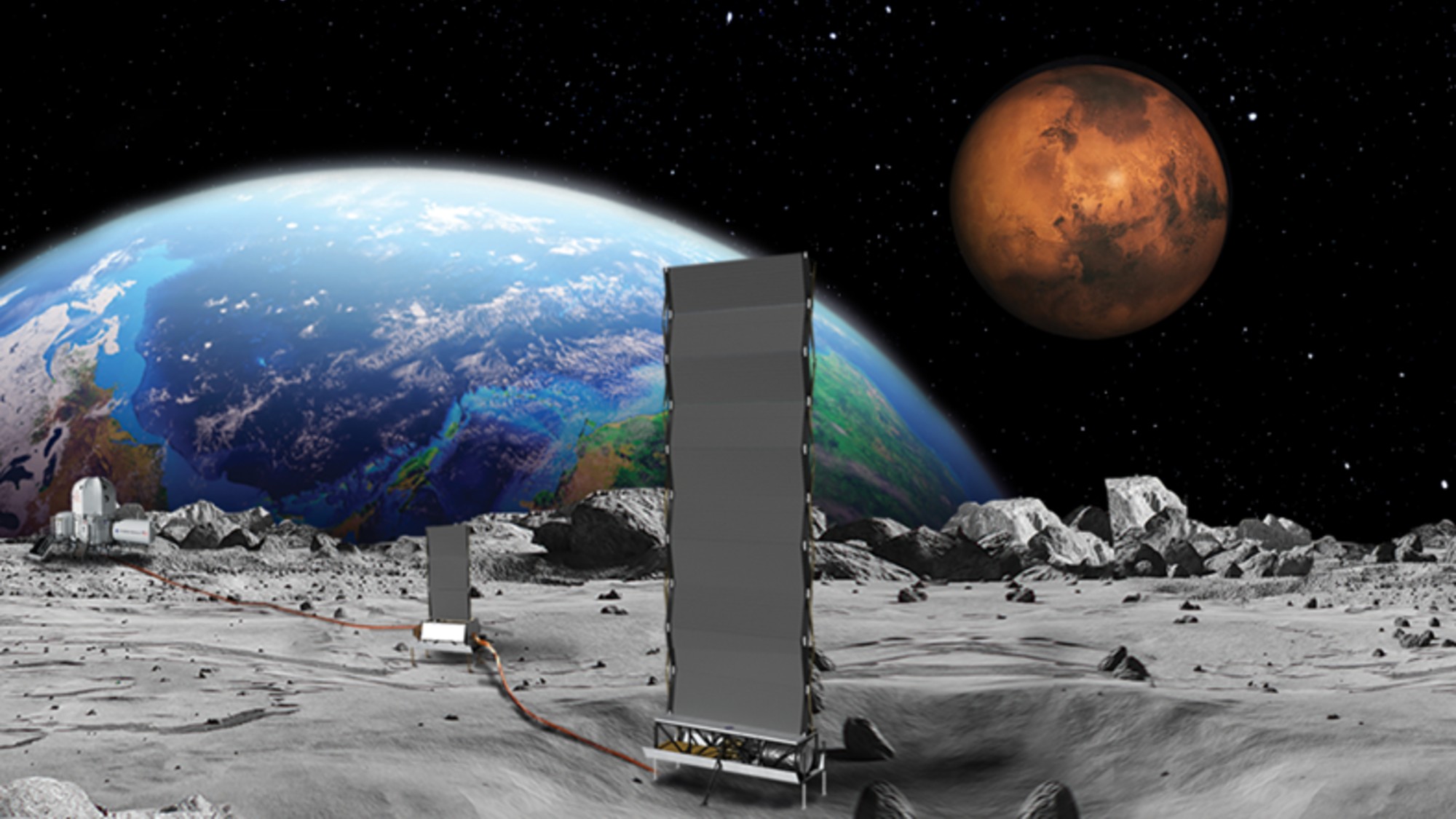

Why does the US want to put nuclear reactors on the moon?

Why does the US want to put nuclear reactors on the moon?Today's Big Question The plans come as NASA is facing significant budget cuts

-

New York plans first nuclear plant in 36 years

New York plans first nuclear plant in 36 yearsSpeed Read The plant, to be constructed somewhere in upstate New York, will produce enough energy to power a million homes

-

Cautious optimism surrounds plans for the world's first nuclear fusion power plant

Cautious optimism surrounds plans for the world's first nuclear fusion power plantTalking Point Some in the industry feel that the plant will face many challenges

-

How radioactive rhinos may prevent poaching

How radioactive rhinos may prevent poachingUnder The Radar Injecting radioactive material will make horns harder to smuggle internationally

-

5 of the most invasive animal species on the planet

5 of the most invasive animal species on the planetSpeed Read Invasive species are a danger to ecosystems all over the world

-

Wild boars in Europe can’t shake off their radioactivity

Wild boars in Europe can’t shake off their radioactivitySpeed Read Scientists think they may have solved a phenomenon known as the ‘wild boar paradox’

-

Air pollution is now the 'greatest external threat' to life expectancy

Air pollution is now the 'greatest external threat' to life expectancySpeed Read Climate change is worsening air quality globally, and there could be deadly consequences