The rise of the social media influencer

Who exactly are they? And why are they always going to Dubai?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Where did influencers come from?

Ever since the creation of the World Wide Web in 1991, like-minded users have gathered together, first on web forums and bulletin boards, then on blogging sites, and more recently on social media. In the early 2000s, canny marketers started approaching influential bloggers and forum moderators, asking them to promote products in return for freebies, and later for cash. This process became supercharged with the founding of YouTube in 2005, Twitter in 2006, and in 2010, Instagram – which is now most influencers’ platform of choice. Today, there is an army of influencers: social media users – mostly women – with a large, devoted following, who give their followers access to a carefully curated version of their lives. In this “authentic” context, sponsored content, known as “sponcon”, has proved a potent tool for selling products.

Who are these people?

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

There’s a bewildering range, from fashion, lifestyle and “mommy influencers” on Instagram to gamers, beauty vloggers and “toy influencers” on YouTube, to teenagers lip-synching to songs on TikTok. Some of the biggest are famous from another field: last week, the rapper Nicki Minaj wore a pair of bejewelled pink Croc shoes on Instagram, where she has 136 million followers; demand for pink Crocs spiked by 4,900% in hours.

Many of the most famous influencers, such as Kim Kardashian (who has 221 million Instagram followers) graduated from reality TV – another carefully crafted version of “real life”. Then there are people who made themselves famous entirely by posting content on social media: the likes of Logan Paul, PewDiePie or Zoë Sugg, who each speak to tens of millions of people. Marketers now divide them up into nano influencers (1,000-10,000 followers), micro influencers (10,000-100,000), macro influencers (100,000- 1 million) and mega or celebrity influencers (more than 1 million).

How big is the industry?

Very. By the end of 2019, the influencer marketing industry was worth some $8bn a year. One recent report by Insider Intelligence predicted that it would grow to $15bn globally by the end of 2022. The tech consultant SignalFire thinks that “the creator economy” – built by those who post and monetise content online – employs more than 50 million people, and is the fastest-growing sector for small businesses in the world.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

There is now a UK union for influencers, The Creator Union; andaUS trade association, the American Influencer Council. Mega influencers such as Kylie Jenner (233 million followers on Instagram) can earn as much as $1m per post. Even the Government uses them: last year it paid influencers including Love Island stars to promote the NHS Test and Trace service.

What is life like for influencers?

The idea of making thousands of pounds a month by sharing a few selfies may sound cushy – but the reality can be hard. There are the endless hours spent preparing for photo shoots, arranging photographers, changing outfits in cramped “pop-up tents”, editing photos and thinking up envy-inducing captions and hashtags. Demanding clients often force them to endlessly re-shoot photos or videos until they come out just right. There’s the pressure of always seeking to increase your follower count to drive up revenues. But arguably the toughest part, says Amy Hart (1.1 million followers), is negotiating payment in a crowded market. After all, she says, “there are a lot of me. If I turn around and say, ‘No, I want this’, they’ll say, ‘Okay, cool, we’ll go to one of the other 1,500 people who’d be happy to do this’.”

How do businesses judge an influencer’s worth?

In theory, everything online is quantifiable: “engagement” can be recorded, in the form of follower counts, “likes” and views. However, nowadays “engagement fraud” is a big problem: bogus followers can be purchased online, from people who operate fake accounts and bots. An arms race has begun between fraudsters with fake followers and the software developed to detect them. A whole industry has emerged to negotiate it: agencies such as BrandConnect, owned by YouTube, connect influencers with large followings to companies who want to buy “sponcon”.

Do the followers not mind “sponcon”?

Apparently not. “A decade ago, shilling products to your fans may have been seen as selling out. Now it’s a sign of success,” noted Taylor Lorenz, who writes about internet culture for The New York Times. Some fledgling influencers even put out fake sponcon, on the grounds that the more sponsors you have, the more credibility it gives. An influencer culture has developed – or more accurately a series of cultures. The prevailing Instagram culture mixes rampant consumerism with inspirational bromides about self-worth, personal growth and “wellness”. It has also been accused of propagating an unrealistic version of beauty.

What version of beauty?

The New Yorker’s Jia Tolentino noted the gradual emergence, among “professionally beautiful women” today, of a look known as “Instagram face”. It’s “a young face, of course, with poreless skin and plump, high cheekbones”, long lashes and full lips – generally white but with a hint of “rootless exoticism”: you see it among the Kardashian family, and the models Bella Hadid (42 million followers), and Emily Ratajkowski (27 million followers). It is thought to owe its existence partly to the growth of cosmetic procedures, but also to the popularity of Instagram filters such as Facetune, which tweaks images to give a thinner face, bigger lips, smoother skin, larger eyes, and slimmer legs. Professional photos have long been airbrushed; now aspiring influencers can do it at home too.

Dubai: the planet’s influencer capital

Dubai is now “a global hub of influencer culture”, says Ruth Michaelson in The Guardian, “a magnet for social media stars desperate to tweak their image in what has become the ideal Instagram city”. With its reliable sunshine, crystal-clear seas, and a series of signature constructions – the sail-shaped Burj Al Arab hotel, the Palm, and the world’s tallest building, the Burj Khalifa – Dubai is perfect as a backdrop for influencers’ idealised lifestyles.

The city’s authorities have actively encouraged this: there is “The Frame”, a 150-metre gold rectangle through which, at the right angle, the Burj Khalifa can be framed; free helicopter tours are available for those with enough followers. Instagram’s Middle East headquarters are, of course, based there. Dubai has also benefited because it lifted lockdown restrictions for visitors; dubbed the "Covid Casablanca", it allowed some bars, cinemas and clubs to open. Many UK influencers bypassed travel bans on the basis that they were making “essential work trips”. James Lock, star of The Only Way Is Essex, told his followers he was “still grafting” in Dubai. His then-girlfriend, Yazmin Oukhellou, added: “We are here for work purposes, for business... Obviously, we’ll make the most of it while we’re here as well.”

This article was corrected on May 27 to reflect that Dubai lifted its lockdown restrictions to allow visitors

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?Today’s Big Question Democrats want to rein in ICE’s immigration crackdown

-

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

Moltbook: The AI-only social network

Moltbook: The AI-only social networkFeature Bots interact on Moltbook like humans use Reddit

-

Are Big Tech firms the new tobacco companies?

Are Big Tech firms the new tobacco companies?Today’s Big Question A trial will determine whether Meta and YouTube designed addictive products

-

Is social media over?

Is social media over?Today’s Big Question We may look back on 2025 as the moment social media jumped the shark

-

Australia’s teen social media ban takes effect

Australia’s teen social media ban takes effectSpeed Read Kids under age 16 are now barred from platforms including YouTube, TikTok, Instagram, Facebook, Snapchat and Reddit

-

Trump allies reportedly poised to buy TikTok

Trump allies reportedly poised to buy TikTokSpeed Read Under the deal, U.S. companies would own about 80% of the company

-

What an all-bot social network tells us about social media

What an all-bot social network tells us about social mediaUnder The Radar The experiment's findings 'didn't speak well of us'

-

Broken brains: The social price of digital life

Broken brains: The social price of digital lifeFeature A new study shows that smartphones and streaming services may be fueling a sharp decline in responsibility and reliability in adults

-

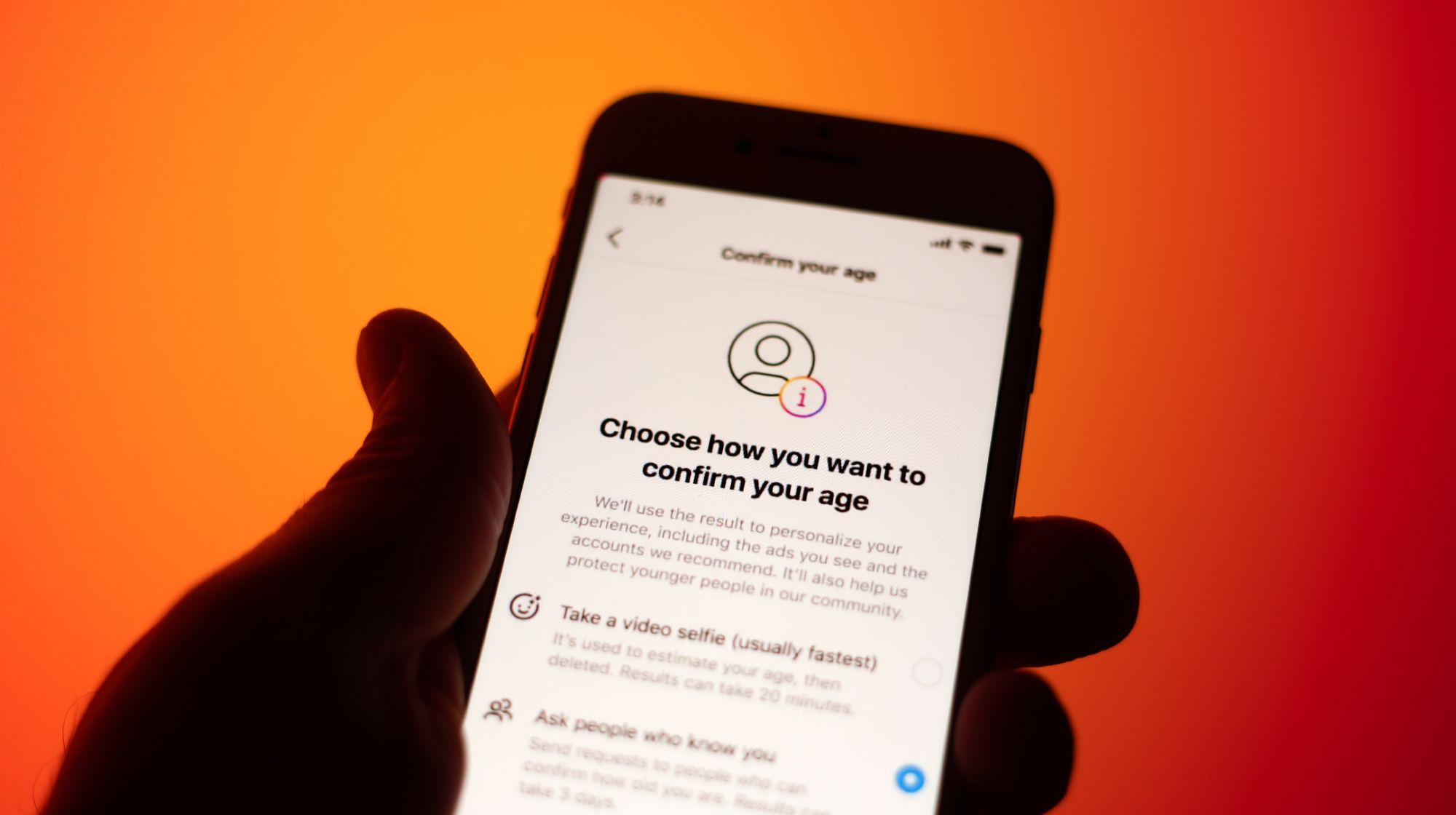

Supreme Court allows social media age check law

Supreme Court allows social media age check lawSpeed Read The court refused to intervene in a decision that affirmed a Mississippi law requiring social media users to verify their ages