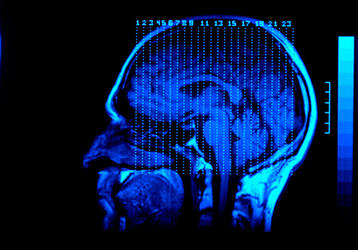

Brain scans might predict recovery potential for vegetative patients

Thinkstock

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Researchers have found that scans that look for signs of metabolic activity in specific areas of the brain could help doctors predict whether a person in a vegetative state will regain consciousness.

The findings were published Tuesday in the journal The Lancet. Researchers in Belgium tracked about 120 subjects — diagnosed as either minimally conscious, locked in, or unresponsively wakeful (vegetative) — for at least one year. When images of the brain were taken with a positron emission tomography (PET) scan, the researchers accurately predicted 74 percent of the time if a patient would show signs of consciousness a year later, and 92 percent of the time if they would remain in a vegetative or minimally conscious state.

In the 41 patients deemed in a vegetative state using normal tests, the PET scan found previously undetected minimal consciousness in 13. A year later, nine of the 13 had progressed into at least a minimally conscious state, three had died, and one was still in a vegetative state.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The metabolic patterns of a brain in a vegetative state look different from those of a brain with intermittent consciousness, the researchers found. The prognosis was best for those who had survived traumatic brain injury, as opposed to someone whose brain was damaged due to hypoxia, a prolonged interruption of oxygenated blood to the brain.

The findings show that PET scans paint a clearer picture of the patient's outcome than the more widely available functional magnetic resonance imaging, or fMRI. The difference between the two is that PET scans detect signs of metabolic activity, while an fMRI detects activity in certain brain regions by looking for oxygenation.

The new research could provide hope, or at least guidance, for the families of vegetative patients. But not all patients with hopeful PET scans will recover. "We shouldn't give these families false hope," report author Steven Laureys tells The New York Times. "This is very difficult. But it's just a very complex medical reality. Quantifying consciousness is tricky."

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Catherine Garcia has worked as a senior writer at The Week since 2014. Her writing and reporting have appeared in Entertainment Weekly, The New York Times, Wirecutter, NBC News and "The Book of Jezebel," among others. She's a graduate of the University of Redlands and the Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism.