Scientists grew nasal cartilage, vaginas, and successfully implanted them in patients

Wake Forest Institute for Regenerative Medicine

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Like scaffolding that props up a building, scientists are now using temporary frameworks to create custom-designed, complex new organs, which they've successfully implanted in several patients. These breakthroughs were revealed in two extraordinary studies on the engineering of body parts published Thursday in The Lancet.

Here's the basics of how the process works: Doctors first extract cells from a patient's muscle and tissue, then use those cells to seed 3-D biodegradable scaffolding of the target organ that they've constructed from scans of the patient's body. After a few weeks in an incubator, the seed cells have spread across the scaffolding to produce a layer of tissue, and the new organ is implanted in the patient. The scaffolding is absorbed into the body as the cells continue to grow.

One team worked on creating nasal cartilage, while another grew new vaginas. "This is a move forward to even more challenging [organs]," Ian Martin, a professor of tissue engineering at University Hospital Basel in Switzerland and co-author of the nasal cartilage study, told CNN. "All these incremental steps finally have demonstrated that it is possible to engineer tissue that can help patients."

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The reproductive organ study involves four teenagers born with a rare condition called Mayer-Rokitansky-Küster-Hauser Syndrome. The women were all born either without or with a deformed uterus or vagina. According to CNN, after receiving their new sex organs, the patients all indicated that they had "normal levels of desire, arousal, lubrication, orgasm, satisfaction, and painless intercourse." Two of the patients now also menstruate.

The patients in the nasal tissue study were all elderly and had recently undergone cancer surgery. Ordinarily, doctors reconstruct noses with big pieces of cartilage taken from the ear, septum, or ribs — a very painful process. This time, scientists removed a tiny piece of tissue from each patient's nasal septum — roughly half the size of the tip of a pen — and put it onto a scaffold. The cells formed a thin layer of cartilage that was then transplanted to the patient.

Scientists hope that these amazing findings will help more people in the future, including those who need replacement cartilage or whose reproductive systems have been damaged. "Tissue engineering is finally demonstrating that it can deliver on expectations," Martin said.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Catherine Garcia has worked as a senior writer at The Week since 2014. Her writing and reporting have appeared in Entertainment Weekly, The New York Times, Wirecutter, NBC News and "The Book of Jezebel," among others. She's a graduate of the University of Redlands and the Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism.

-

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?IN THE SPOTLIGHT As the president muses about polling place deployments and a centralized electoral system aimed at one-party control, lawmakers are taking this administration at its word

-

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

Earth is rapidly approaching a ‘hothouse’ trajectory of warming

Earth is rapidly approaching a ‘hothouse’ trajectory of warmingThe explainer It may become impossible to fix

-

‘One Battle After Another’ wins Critics Choice honors

‘One Battle After Another’ wins Critics Choice honorsSpeed Read Paul Thomas Anderson’s latest film, which stars Leonardo DiCaprio, won best picture at the 31st Critics Choice Awards

-

Son arrested over killing of Rob and Michele Reiner

Son arrested over killing of Rob and Michele ReinerSpeed Read Nick, the 32-year-old son of Hollywood director Rob Reiner, has been booked for the murder of his parents

-

Rob Reiner, wife dead in ‘apparent homicide’

Rob Reiner, wife dead in ‘apparent homicide’speed read The Reiners, found in their Los Angeles home, ‘had injuries consistent with being stabbed’

-

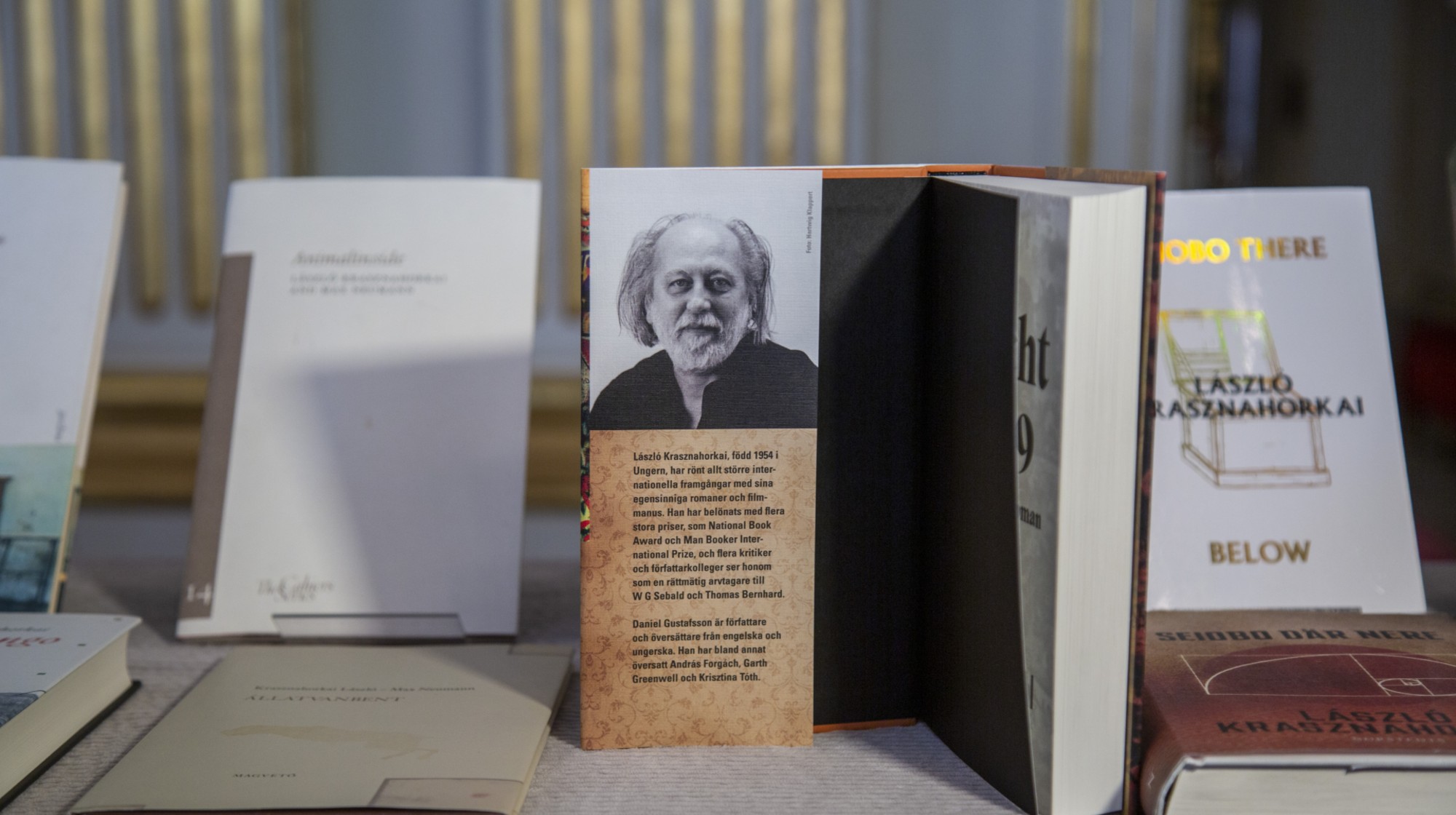

Hungary’s Krasznahorkai wins Nobel for literature

Hungary’s Krasznahorkai wins Nobel for literatureSpeed Read László Krasznahorkai is the author of acclaimed novels like ‘The Melancholy of Resistance’ and ‘Satantango’

-

Primatologist Jane Goodall dies at 91

Primatologist Jane Goodall dies at 91Speed Read She rose to fame following her groundbreaking field research with chimpanzees

-

Florida erases rainbow crosswalk at Pulse nightclub

Florida erases rainbow crosswalk at Pulse nightclubSpeed Read The colorful crosswalk was outside the former LGBTQ nightclub where 49 people were killed in a 2016 shooting

-

Trump says Smithsonian too focused on slavery's ills

Trump says Smithsonian too focused on slavery's illsSpeed Read The president would prefer the museum to highlight 'success,' 'brightness' and 'the future'

-

Trump to host Kennedy Honors for Kiss, Stallone

Trump to host Kennedy Honors for Kiss, StalloneSpeed Read Actor Sylvester Stallone and the glam-rock band Kiss were among those named as this year's inductees