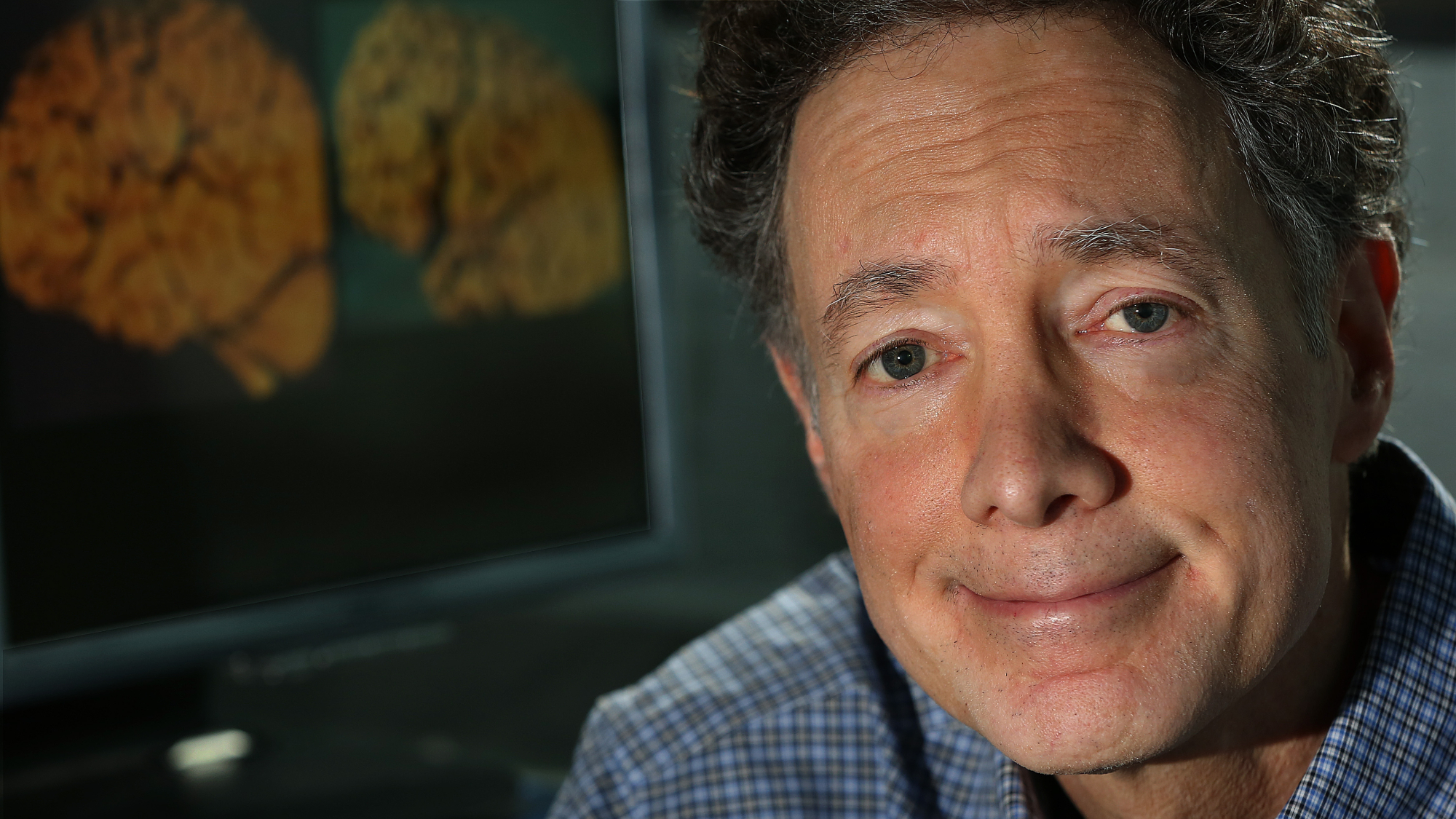

Hibernating bears could hold the key to Alzheimer's treatment

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

There's no known cure for Alzheimer's disease, but scientists may be one step closer to treating the condition. And it's all thanks to bears' hibernation.

Scientists at the University of Leicester in England simulated bears' hibernation process in mice, who don't normally go into hibernation. They then studied the mice's brains and found a way to prevent the loss of brain cells.

Vice explains that during bears' hibernation, their body temperatures decrease, and synapses between brain cells are decreased. As the bears' temperatures increase when winter is over, their brain cell connections are restored, thanks to RBM3, a "cold shock" protein. When the researchers decreased the body temperatures of mice bred to develop neurological disorders, they found that both brain cell regeneration and RBM3 levels decreased as the diseases worsened.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

But when the researchers gave the "neurologically compromised" mice higher levels of RBM3, their brain cell connections didn't deteriorate. The researchers concluded that RBM3 "could help protect brain function without the need for cooling core body temperature," according to Vice. The scientists are now searching for a way to mimic the effects of brain cooling.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Meghan DeMaria is a staff writer at TheWeek.com. She has previously worked for USA Today and Marie Claire.

-

Should the EU and UK join Trump’s board of peace?

Should the EU and UK join Trump’s board of peace?Today's Big Question After rushing to praise the initiative European leaders are now alarmed

-

Antonia Romeo and Whitehall’s women problem

Antonia Romeo and Whitehall’s women problemThe Explainer Before her appointment as cabinet secretary, commentators said hostile briefings and vetting concerns were evidence of ‘sexist, misogynistic culture’ in No. 10

-

Local elections 2026: where are they and who is expected to win?

Local elections 2026: where are they and who is expected to win?The Explainer Labour is braced for heavy losses and U-turn on postponing some council elections hasn’t helped the party’s prospects

-

Blue Origin launches Mars probes in NASA debut

Blue Origin launches Mars probes in NASA debutSpeed Read The New Glenn rocket is carrying small twin spacecraft toward Mars as part of NASA’s Escapade mission

-

Dinosaurs were thriving before asteroid, study finds

Dinosaurs were thriving before asteroid, study findsSpeed Read The dinosaurs would not have gone extinct if not for the asteroid

-

SpaceX breaks Starship losing streak in 10th test

SpaceX breaks Starship losing streak in 10th testspeed read The Starship rocket's test flight was largely successful, deploying eight dummy satellites during its hour in space

-

Rabbits with 'horns' sighted across Colorado

Rabbits with 'horns' sighted across Coloradospeed read These creatures are infected with the 'mostly harmless' Shope papilloma virus

-

Lithium shows promise in Alzheimer's study

Lithium shows promise in Alzheimer's studySpeed Read Potential new treatments could use small amounts of the common metal

-

Scientists discover cause of massive sea star die-off

Scientists discover cause of massive sea star die-offSpeed Read A bacteria related to cholera has been found responsible for the deaths of more than 5 billion sea stars

-

'Thriving' ecosystem found 30,000 feet undersea

'Thriving' ecosystem found 30,000 feet underseaSpeed Read Researchers discovered communities of creatures living in frigid, pitch-black waters under high pressure

-

New York plans first nuclear plant in 36 years

New York plans first nuclear plant in 36 yearsSpeed Read The plant, to be constructed somewhere in upstate New York, will produce enough energy to power a million homes