Deadly pandemics usually feature denial from leaders, often prioritizing money, historians say

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The COVID-19 "plague," as President Trump likes to call it, is caused by a new coronavirus. But viral pandemics and deadly plagues aren't new. And neither is initially pretending the disease won't affect your region, or prematurely declaring victory.

"A century ago, the Spanish flu epidemic's second wave was far deadlier than its first, in part because authorities allowed mass gatherings from Philadelphia to San Francisco," The Associated Press reports in an article about the "growing dread" health experts feel about "an all-but-certain second wave of deaths and infections that could force governments to clamp back down." In the U.S., the first wave hasn't yet crested.

"Almost every epidemic you can think of, the first reaction of any government is to say, 'No, no, it's not here. We haven't got it,'" British historian and pandemic researcher Richard Evans tells NPR. "Or 'it's only mild' or 'it's not going to have a big effect.'" In nearly every case, the government was dead wrong, Evans said. NPR looked at the example he laid out in his 1987 book about the 1892 cholera outbreak in Hamburg, Germany, which killed about 10,000 of the port city's 800,000 residents. NPR summarized some key points:

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The German city-state was run by merchant families who put trade and economy above residents' welfare. ... Hamburg's leaders claimed cholera was spread by an invisible vapor no government could hope to prevent. But in August 1892, the excrement of a Russian migrant ill with cholera ended up in the Elbe River, which the city drew on for its municipal water. ...Hamburg's government waited six days after discovering that people were dying from cholera to tell anyone. By then, thousands were ill. ... A year after the cholera outbreak, Hamburg's fed-up citizenry voted their incompetent businessmen leaders out of office. They replaced the merchants with leaders who belonged to the Social Democrats, a working-class party that prioritized science and health over profit. [NPR]

Merchants were also blamed in the Great Plague of Marseille, the last major outbreak of the bubonic plague in Western Europe

Luckily, science has come a long way in the past 130 years. Politics? Maybe not.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Peter has worked as a news and culture writer and editor at The Week since the site's launch in 2008. He covers politics, world affairs, religion and cultural currents. His journalism career began as a copy editor at a financial newswire and has included editorial positions at The New York Times Magazine, Facts on File, and Oregon State University.

-

Political cartoons for February 20

Political cartoons for February 20Cartoons Friday’s political cartoons include just the ice, winter games, and more

-

Sepsis ‘breakthrough’: the world’s first targeted treatment?

Sepsis ‘breakthrough’: the world’s first targeted treatment?The Explainer New drug could reverse effects of sepsis, rather than trying to treat infection with antibiotics

-

James Van Der Beek obituary: fresh-faced Dawson’s Creek star

James Van Der Beek obituary: fresh-faced Dawson’s Creek starIn The Spotlight Van Der Beek fronted one of the most successful teen dramas of the 90s – but his Dawson fame proved a double-edged sword

-

TikTok secures deal to remain in US

TikTok secures deal to remain in USSpeed Read ByteDance will form a US version of the popular video-sharing platform

-

Unemployment rate ticks up amid fall job losses

Unemployment rate ticks up amid fall job lossesSpeed Read Data released by the Commerce Department indicates ‘one of the weakest American labor markets in years’

-

US mints final penny after 232-year run

US mints final penny after 232-year runSpeed Read Production of the one-cent coin has ended

-

Warner Bros. explores sale amid Paramount bids

Warner Bros. explores sale amid Paramount bidsSpeed Read The media giant, home to HBO and DC Studios, has received interest from multiple buying parties

-

Gold tops $4K per ounce, signaling financial unease

Gold tops $4K per ounce, signaling financial uneaseSpeed Read Investors are worried about President Donald Trump’s trade war

-

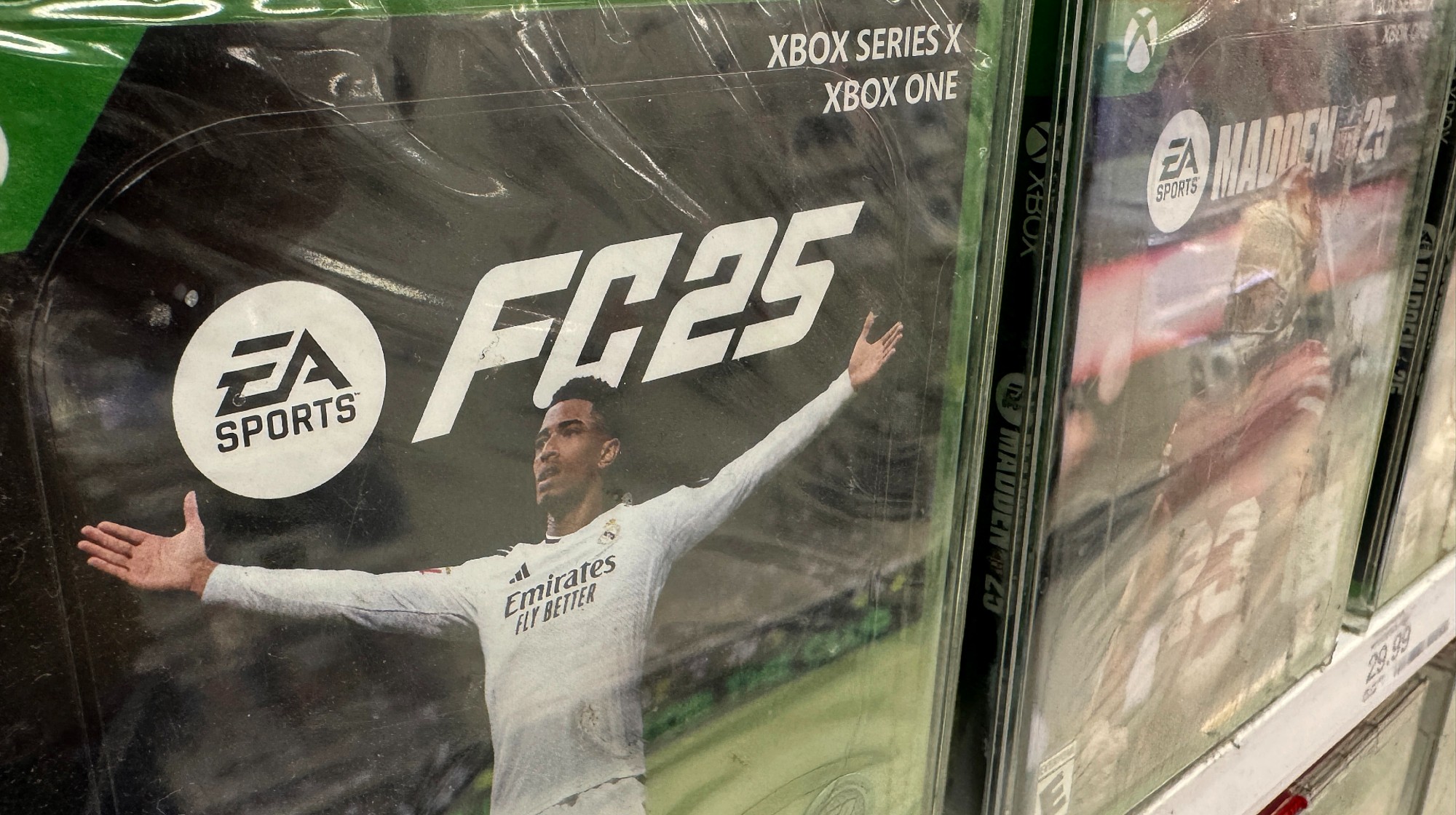

Electronic Arts to go private in record $55B deal

Electronic Arts to go private in record $55B dealspeed read The video game giant is behind ‘The Sims’ and ‘Madden NFL’

-

New York court tosses Trump's $500M fraud fine

New York court tosses Trump's $500M fraud fineSpeed Read A divided appeals court threw out a hefty penalty against President Trump for fraudulently inflating his wealth

-

Trump said to seek government stake in Intel

Trump said to seek government stake in IntelSpeed Read The president and Intel CEO Lip-Bu Tan reportedly discussed the proposal at a recent meeting