Sumo wrestling is taking a beating

Scandals and high-profile resignations of former stars have 'sullied' image of Japan's national sport – but could its latest star turn the tide?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The man widely considered to be the greatest sumo wrestler in history has resigned, compounding a bruising few years for Japan's ancient sport.

Last week Hakuho Sho left the Japan Sumo Association (JSA), the sport's governing body, the latest in a series of resignations among yokozuna, the highest-ranking wrestlers. Now, only four of the 10 most recently retired grand champions are still in the JSA.

"It's a significant loss of high-level experience and one that hurts sumo's efforts to both find and keep young talent in the sport," said The Japan Times. And the resignation of Hakuho – the most decorated wrestler in sumo history "by a significant margin", as well as a "major recruiter of talent" – is the "biggest blow of all".

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

'Sullied' samurai values

The origins of sumo date back more than 1,000 years, but Japan is the only place where it is "contested on a professional level", said The Independent. It is widely considered Japan's national sport, with many "ritual elements" connected to the indigenous religion, Shinto. Sumo is "highly regimented"; many wrestlers live in training facilities where "food and dress are controlled by ancient traditions".

Sumo "prides itself on being a repository of the samurai values of courage, determination and loyalty", said The Times. But that image has been "sullied" in recent years. The sport has been "plagued" by scandals involving "violence, match-fixing and mismanagement". Japan's dramatically falling birth rate has also "hurt sumo". According to government data released this week, Japan's birth rate dropped by 5.7% between 2023 and 2024. Last spring only 34 people applied to become wrestlers – known as rikishi – down from 160 at the peak in 1992. To "lure young recruits", the governing body relaxed the minimum standards for height and weight.

One wrestler's ascendance is seen as a "chance to increase the sport's popularity", and distance it from its controversies. Sumo may have its "smiling 30-stone champion": Onosato.

Onosato was promoted to the rank of yokozuna last month, "completing a meteoric rise to the summit" of sumo in a record span of just 13 tournaments, said The Guardian. Born Daiki Nakamura, he is the 75th yokozuna in sumo's history, and at age 24 the youngest since 1994. He's also the first Japanese-born sumo wrestler since 2017; in recent years Mongolian-born athletes like Hakuho have "dominated". His rise has been "widely hailed both for its symbolic significance and his calm, composed style".

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

"I hope he leads by example and lifts the entire world of sumo," said Nishonoseki, Onosato's stablemaster, who competed as Kisenosato.

A few big buts

But wrestlers who exert "total dominance" inside the ring often struggle with the strict rules and conventions of sumo, said The Japan Times. They are regularly "chastised".

Still, official censure or "condemnation by the media" is "easier to handle when you are top of the world and raking in trophies and prize money". But "it's a completely different situation when the limelight and all the perks are suddenly gone".

For wrestlers such as Hakuho, sumo is all they know. There are "few, if any, opportunities to develop the kind of skills and mechanisms needed to cope with the emotional turmoil that comes from such a sudden shift".

What makes the adjustment even harder is the "rigid nature of life" after retirement from sumo. For those who choose to remain with the JSA as coaches or stablemasters, there is "still little freedom in how they choose to live their lives day to day".

Now, after Hakuho's resignation, the future of his namesake event is unclear. The Hakuho Cup is "arguably the most important sumo tournament in the world" for children and adolescents.

For Onosato, like numerous current wrestlers, the cup was a "major milestone and motivator". It provides "invaluable experience for children from numerous countries", and was a link between amateur and professional sumo.

The JSA will "continue to survive and thrive", but it's hard to argue that "sumo hasn't been lessened without its most decorated champion". For the sake of its future, sumo should "figure out a way to stem the tide of such high-profile departures".

Harriet Marsden is a senior staff writer and podcast panellist for The Week, covering world news and writing the weekly Global Digest newsletter. Before joining the site in 2023, she was a freelance journalist for seven years, working for The Guardian, The Times and The Independent among others, and regularly appearing on radio shows. In 2021, she was awarded the “journalist-at-large” fellowship by the Local Trust charity, and spent a year travelling independently to some of England’s most deprived areas to write about community activism. She has a master’s in international journalism from City University, and has also worked in Bolivia, Colombia and Spain.

-

Local elections 2026: where are they and who is expected to win?

Local elections 2026: where are they and who is expected to win?The Explainer Labour is braced for heavy losses and U-turn on postponing some council elections hasn’t helped the party’s prospects

-

6 of the world’s most accessible destinations

6 of the world’s most accessible destinationsThe Week Recommends Experience all of Berlin, Singapore and Sydney

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

Zhao Xintong: China's controversial snooker champion

Zhao Xintong: China's controversial snooker championIn the Spotlight The 28-year-old was implicated in the sport's biggest match-fixing scandal before coming back from suspension to take the world title

-

MLB is bringing home top talent from Japan's most popular sport

MLB is bringing home top talent from Japan's most popular sportThe Explainer Players like Shohei Ohtani have become the face of Major League Baseball

-

How should the cricketing world handle Afghanistan?

How should the cricketing world handle Afghanistan?Talking Point England under pressure to boycott upcoming men's match against the nation, which remains an ICC member despite Taliban ban on women's team

-

South Sudan's basketball stars

South Sudan's basketball starsUnder the Radar Men's national team qualified for Olympics against the odds and are now inspiring a new generation of players

-

Ukraine's Olympians: going for gold in the line of fire

Ukraine's Olympians: going for gold in the line of fireUnder the Radar Hundreds of the country's athletes have died in battle, while those who remain deal with the psychological toll of war and prospect of Russian competitors

-

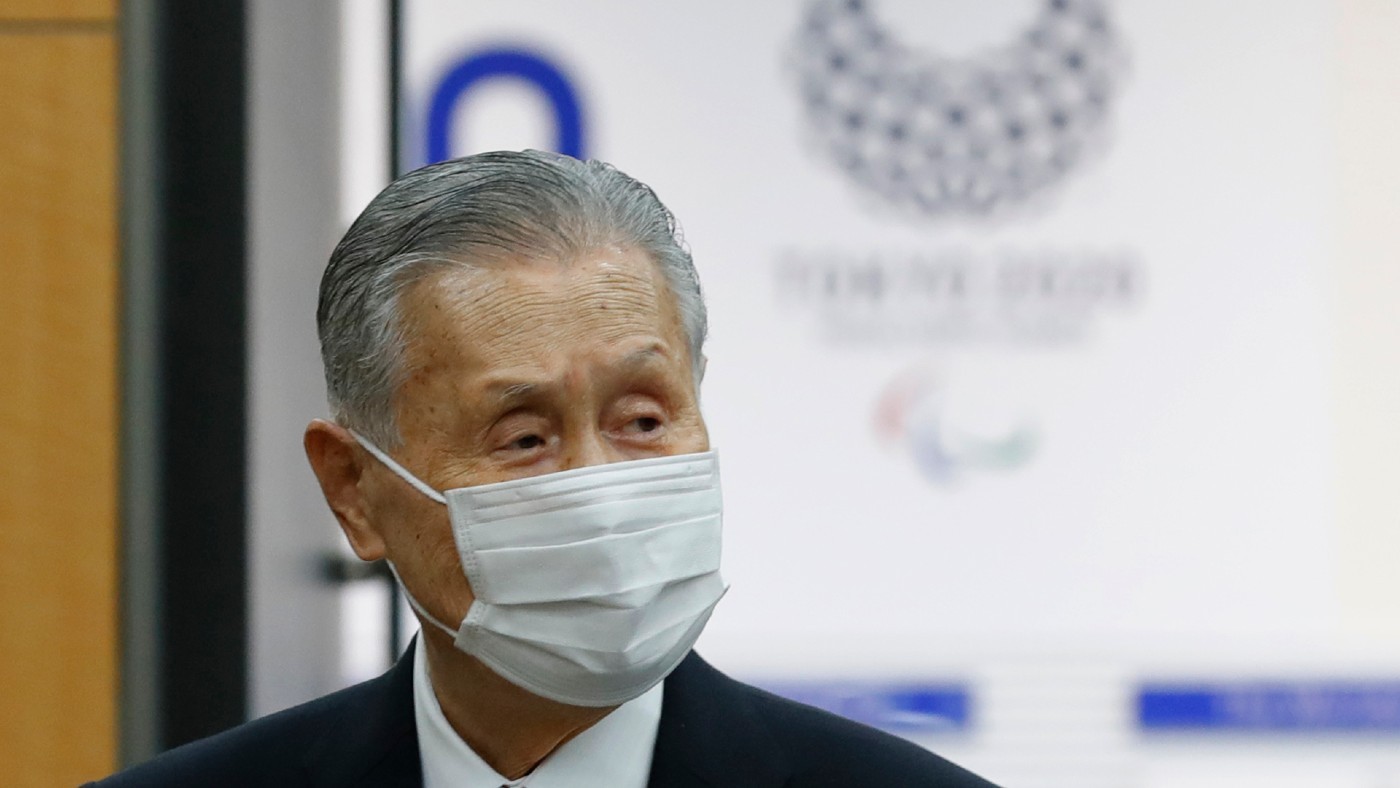

Why cancelling the Tokyo Olympics isn’t Japan’s call

Why cancelling the Tokyo Olympics isn’t Japan’s callfeature Latest polls show Japanese public want the Games axed owing to Covid fears - but who gets the final say?

-

Tokyo Olympic chief refuses to resign over sexist comments

Tokyo Olympic chief refuses to resign over sexist commentsIn the Spotlight Former Japanese PM Yoshiro Mori apologises for saying women talk too much in meetings

-

Could Japan join the Six Nations championship?

Could Japan join the Six Nations championship?Speed Read World Cup hosts would be a more attractive proposition for fans than Italy