The debate over banning chocolate milk in school cafeterias

Why questions about nutrition in the lunchroom have divided parents and officials

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Chocolate milk could soon be history in public school cafeterias. The U.S. Department of Agriculture is considering imposing sugar limits that could amount to a ban on flavored milk in elementary and middle schools under proposed new standards for school meals. The rules would cap sugar content for the first time, targeting such sugary lunch-room staples as breakfast cereal, yogurt, desserts, and chocolate and strawberry milk to help improve kids' health and fight childhood obesity, which federal panels have linked to consuming too much sugar.

The rules would take effect over seven years, starting next school year. They would limit added sugar found in processed foods and drinks, not those found naturally in things like fruit and plain milk. New York City considered but abandoned a similar ban earlier this year; Washington, D.C., and San Francisco have adopted local moratoriums on serving schoolkids flavored milk, which a 2021 study published in the National Library of Medicine identified as the leading source of added sugar in school cafeteria meals.

"The issue has divided parents, child-nutrition specialists, school-meal officials and others," said The Wall Street Journal. People who want children to drink less flavored milk say children accustomed to its sweet taste tend to reject healthier drinks, increasing the risk of obesity. But others say children need the nutrients milk provides, and many won't drink it if it's plain. Who will, and who should, win the debate over chocolate milk?

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Banning chocolate milk will backfire

Some kids won't drink milk if it's not flavored, said Mike Borges and Betty Crocker in USA Today. Trying to force kids to eat things they don't like, such as whole grains and plain milk, is a losing battle, because those aren't the things they choose when they're not in school. If you eliminate the very things that make cafeteria food palatable to them, "more students — many of whom rely on school meals as their main or only source of nutrition and calories — are likely to toss their lunch trays." A better way to help kids eat healthier is to "provide schools with the resources to create a culture of holistic nutrition education by making it an integral part of the curriculum." In other words, help kids make healthier choices.

These "nanny state" technocrats trying to tell kids — and parents — what to do must be stopped, said Nate Hochman in National Review in February, when New York considered banning chocolate milk in schools. The liberals pushing these bans think they've been "divinely appointed to organize and direct the day-to-day decisions of the people they govern." But now they've gone too far! "We're talking about chocolate milk here — a staple of American childhood." This debate is "a testament to the utterly bleak, joyless world that progressive central planners would inflict on us all, if given the chance."

Cutting sugar and sodium is good for kids

Changing the menu will be hard, but worth it, said the Los Angeles Times in an editorial. Cutting sugar and sodium, and increasing whole grains in school cafeterias "are reasonable, necessary changes considering that about 1 in 5 U.S. children are obese, a condition that can lead to serious lifelong health consequences if it continues into adulthood." It does mean that schools will have to "cut some products, replacing them with ones that meet the new sugar and sodium guidelines." But that doesn't spell doom for chocolate-milk lovers. The International Dairy Foods Association has said "it would voluntarily reduce sugars in flavored milk so that children could still have the option," which means kids would still get the taste of chocolate and strawberry plus the calcium, protein, and additional nutrients they need from milk.

Letting kids consume junk in elementary school is a bad idea with lasting consequences, Erin Hennessy, a professor at the Friedman School of Nutrition Science and Policy at Tufts University, told The Wall Street Journal. "We know taste and food preferences really do form early in life and stay with you. The more protective we can be of our children during those developmental windows is a good thing in the long run." And the USDA is proposing "phasing in these changes gradually," said Wendy Wisner in Parents.com, which will keep them fed while getting them used to the healthier diet. "The USDA based its guidelines on both wanting to introduce healthier options, but also recognizing that kids are kids, and suddenly changing the amount of sugar and salt in school lunches might not fly with most."

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Harold Maass is a contributing editor at The Week. He has been writing for The Week since the 2001 debut of the U.S. print edition and served as editor of TheWeek.com when it launched in 2008. Harold started his career as a newspaper reporter in South Florida and Haiti. He has previously worked for a variety of news outlets, including The Miami Herald, ABC News and Fox News, and for several years wrote a daily roundup of financial news for The Week and Yahoo Finance.

-

6 of the world’s most accessible destinations

6 of the world’s most accessible destinationsThe Week Recommends Experience all of Berlin, Singapore and Sydney

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?Today’s Big Question Democrats want to rein in ICE’s immigration crackdown

-

Scientists are worried about amoebas

Scientists are worried about amoebasUnder the radar Small and very mighty

-

A Nipah virus outbreak in India has brought back Covid-era surveillance

A Nipah virus outbreak in India has brought back Covid-era surveillanceUnder the radar The disease can spread through animals and humans

-

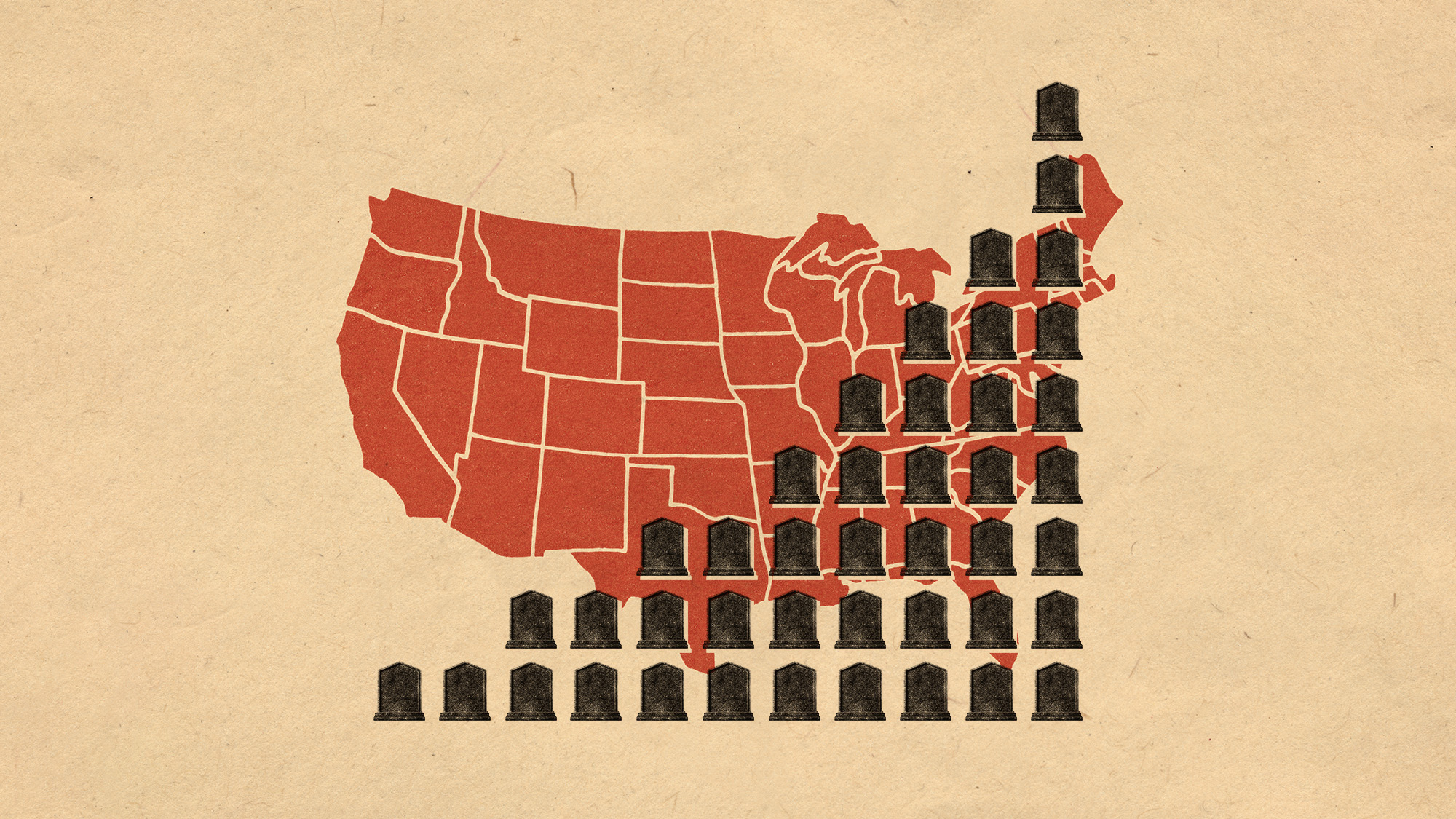

Deaths of children under 5 have gone up for the first time this century

Deaths of children under 5 have gone up for the first time this centuryUnder the radar Poor funding is the culprit

-

A fentanyl vaccine may be on the horizon

A fentanyl vaccine may be on the horizonUnder the radar Taking a serious jab at the opioid epidemic

-

Health: Will Kennedy dismantle U.S. immunization policy?

Health: Will Kennedy dismantle U.S. immunization policy?Feature ‘America’s vaccine playbook is being rewritten by people who don’t believe in them’

-

More adults are dying before the age of 65

More adults are dying before the age of 65Under the radar The phenomenon is more pronounced in Black and low-income populations

-

Ultra-processed America

Ultra-processed AmericaFeature Highly processed foods make up most of our diet. Is that so bad?

-

Climate change is getting under our skin

Climate change is getting under our skinUnder the radar Skin conditions are worsening because of warming temperatures