Rick Scott's plan shows the problem with Congress

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Do Republicans need an agenda? Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-KY) doesn't think so. Asked in January what the GOP might do if it wins the majority in upcoming congressional elections, McConnell replied, "I'll let you know when we take it back."

There's a certain logic in McConnell's answer. As my colleague Peter Weber observes, if you don't propose an agenda, you can't be blamed if you don't keep your promises — or attacked if you do.

Running purely as an alternative to the incumbents has its own disadvantages, though. Parties can take power on the basis of public dissatisfaction and negative partisanship. But that isn't usually enough to sustain them in legislative efforts. There's no question that McConnell wants more Republicans on Capitol Hill. It's less clear that he wants to do much with them once they're seated.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

That's why I suggested a 10-point agenda for Congressional Republicans in a column last month. Although it was rhetorically modeled on the 1994 Contract With America, the plan was less a detailed policy proposal than a thought experiment in which I attempted to imagine a positive agenda that could appeal to different factions within the congressional party as well as to swing voters. Not all of the items reflected my own preferences or priorities. But all were pitched to an electorate that I read as craving stability and normality after years of upheaval.

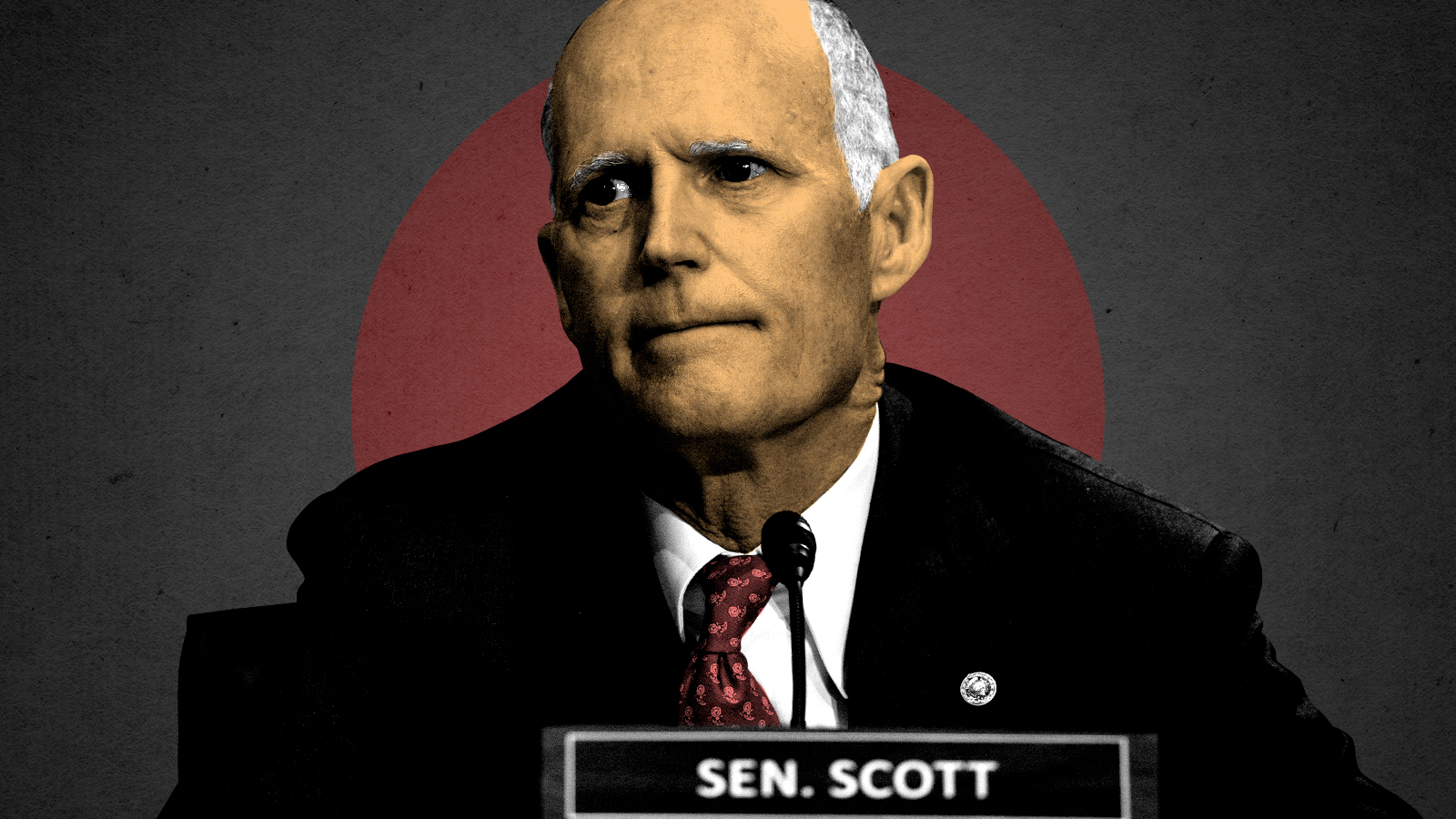

It seems that Sen. Rick Scott (R-Fla.) has a different assessment. There's some overlap with my suggestions. But the "11 Point Plan to Rescue America" that Scott's office issued this week goes much harder on culture war, while soft-pedaling material concerns and pandemic-related issues.

One item has come in for particular derision. In the libertarian-tinged section on economics, Scott argues, "All Americans should pay some income tax to have skin in the game, even if a small amount." He goes on to note that over half of filers owe no net federal income taxes. Democrats were delighted to argue that Scott's proposing a tax increase on tens of millions of poorer Americans. (Scott disputed this characterization in an interview with Sean Hannity).

There are other tensions, too. Several measures Scott proposes are outside the power of the federal government, blocked by major judicial precedents, or would involve repealing or revising landmark legislation. For example, Scott proposes to ban the federal government from collecting racial data of any kind. Whether or not French-style colorblindness is a good idea in itself, such an effort would place congressional Republicans on a collision course with the Civil Rights and Voting Rights Acts. Without support from the White House and overwhelming popular support, that's likely a suicide mission.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

But the truth is, Scott's plan, which he issued in his own name rather than as chairman of the National Republican Senatorial Committee, isn't really a blueprint for legislation — or even for a coordinated campaign. It's an effort to reserve a place in the 2024 presidential primaries in the event that Trump doesn't run. And that reveals a problem with Congress that runs deeper than Rick Scott, Mitch McConnell, or the upcoming midterms. Rather than a legislative body at the heart of our republic, it's increasingly a platform for members' bids for different offices.

Samuel Goldman is a national correspondent at TheWeek.com. He is also an associate professor of political science at George Washington University, where he is executive director of the John L. Loeb, Jr. Institute for Religious Freedom and director of the Politics & Values Program. He received his Ph.D. from Harvard and was a postdoctoral fellow in Religion, Ethics, & Politics at Princeton University. His books include God's Country: Christian Zionism in America (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2018) and After Nationalism (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2021). In addition to academic research, Goldman's writing has appeared in The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, and many other publications.