The Windrush scandal and the Jamaica deportation flight: what you need to know

Plane carrying detainees leaves UK despite 11th-hour court ruling

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The Home Office has gone ahead with a deportation flight to Jamaica despite campaigners winning a last-minute court battle to get reprieves for some of the detainees.

A Court of Appeal judge told the Government yesterday that some of the detainees had not had access to proper legal advice and ordered that their planned deportation be cancelled.

Defending the decision to proceed with the flight, Chancellor Sajid Javid told BBC Radio 5 Live that those who were deported were “not British”, adding: “They are responsible for crimes like manslaughter, rape, dealing in class A drugs.”

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

So who was deported?

Javid told the BBC that those due to be on board the flight had all received “custodial sentences of 12 months or more”.

When asked how many people were on board, the chancellor said he believed it was “around 20, or above 20”.

Approximately 56 people were originally thought to have been due to be deported, The Guardian reports.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Javid also said that those being deported were not members of the Windrush generation but rather offenders who posed a risk to the public.

However, migrant rights charity Detention Action says some of the people affected have lived in the UK since they were children, committed one-time offences when they were young and have no links with Jamaica, reports ITV News.

In a statement, the Joint Council for the Welfare of Immigrants (JCWI) said: “Our thoughts are with the families who have just been forced apart by the Government, with the children who have lost their fathers, with the women who’ve become single mothers overnight.”

Labour MP David Lammy says that the “echoes of Windrush are deafening”.

“Regardless of criminal convictions, it is a breach of human rights legislation to deport individuals to a country where their lives could be in serious danger,” he writes in an article for The Guardian. The newspaper has reported that at least five people have been killed after being deported to Jamaica, he notes.

Lammy says that a number of the detained individuals moved to the UK when they were between two and 11. “Six detainees had indefinite leave to remain in the UK – and a number of them could have received British citizenship as children but were unable to afford the high fees,” he adds.

Why did the court oppose the deportation?

A Court of Appeal judge ordered the Home Office not to carry out the scheduled deportation amid concerns that mobile phone outages had prevented detainees from having access to legal advice.

The Guardian reports that the judge said “detainees should not be removed unless the Home Office was satisfied they ‘had access to a functioning, non-O2 Sim card on or before 3 February’”.

The action was brought by campaigners following a problem with the O2 phone network in Heathrow detention centres.

More than 150 cross-party MPs had also written to Boris Johnson urging him to stop the deportation until a report is published on the lessons learned from the Windrush scandal.

Who are the Windrush generation?

The Windrush scandal saw Commonwealth nationals living in the UK wrongly threatened with deportation and deprived of medical care because they lacked the correct documentation.

The group comprises British citizens who came to the UK from the Commonwealth as children following the Second World War, and whose rights were guaranteed in the Immigration Act of 1971.

Named the Windrush generation after British ship the Empire Windrush - which arrived at Tilbury Docks in Essex carrying 492 Caribbean passengers in 1948 - an estimated 500,000 people now live in the UK who came here from Caribbean countries between 1948 and 1971.

A large number arrived as children, and “many have made the UK their home for their entire lives”, says Channel 4 News.

However, under changes to the immigration law in 2012, these people were forced to prove continuous residence in the UK since 1973, which proved almost impossible for those who had not kept up detailed records.

As a result, some were denied access to state healthcare, made redundant from their jobs and even threatened with deportation, The Guardian reports.

A Home Office review of 11,800 Caribbean cases identified 164 people who were removed or detained who might have been resident in the UK before 1973.

Why was this happening?

The problem follows the ending of a previous system of Commonwealth citizenship and free movement, when status was conferred by law on people to safeguard them but when some did not acquire the necessary papers, according to immigration law blog Free Movement.

This lack of papers was then exacerbated by then prime minister Theresa May’s “hostile environment policy, under which landlords, hospitals, businesses and civil society have been forced to proactively prove that their employees, tenants and service users have the right to be in the United Kingdom”, as the New Statesman’s Stephen Bush reported in 2018.

The policy was introduced to achieve the government’s lower migration targets, by making “living in the UK so unbearable that immigrants will decide to leave of their own accord”, according to Bush.

What “seemed like a politically savvy policy of creating ‘very hostile environments’ for illegal immigrants now looks like a tin-eared, uncaring threat to people with every right to be here”, added The Times’ Matt Chorley.

Former MP Amber Rudd was forced to stand down as a minister in April 2019 after admitting that she had “inadvertently misled” MPs by erroneously stating that the government did not have targets for removing illegal immigrants.

Has anything changed?

The Tory government vowed that all Windrush-generation immigrants would be granted the citizenship papers to which they were entitled, and that application fees would be waived. Those who suffered as a result of the policy change would also receive compensation, officials said.

The scheme now in force makes payments compensating for loss of earnings, impact on family life and the distress resulting from being wrongly detained. But critics say that the payments offered are far too low, and that the mechanism to receive payouts is too complicated for applicants to complete without assistance.

The scheme only compensates victims for a maximum of twelve months’ loss of earnings, but many people were unemployed for much longer, says The Guardian.

Glenda Caesar, a recipient of one of the first Windrush compensation offers, told the newspaper last month that she planned to turn down the payout, which totalled £22,264.

Caesar came to Britain legally from Dominica in 1961 as a three-month-old child, and has remained in the UK since. But because she was unable to probe to the Home Office that she had a right to live in the UK, she lost her job in 2009 and was denied benefits.

A Home Office spokesperson said: “We are determined to right the wrongs experienced by the Windrush generation. The Windrush compensation scheme has been carefully designed with independent oversight to ensure that we deliver on that commitment and to make sure those who are eligible are compensated.”

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?Today’s Big Question Democrats want to rein in ICE’s immigration crackdown

-

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

ICE eyes new targets post-Minnesota retreat

ICE eyes new targets post-Minnesota retreatIn the Spotlight Several cities are reportedly on ICE’s list for immigration crackdowns

-

How corrupt is the UK?

How corrupt is the UK?The Explainer Decline in standards ‘risks becoming a defining feature of our political culture’ as Britain falls to lowest ever score on global index

-

How did ‘wine moms’ become the face of anti-ICE protests?

How did ‘wine moms’ become the face of anti-ICE protests?Today’s Big Question Women lead the resistance to Trump’s deportations

-

The UK expands its Hong Kong visa scheme

The UK expands its Hong Kong visa schemeThe Explainer Around 26,000 additional arrivals expected in the UK as government widens eligibility in response to crackdown on rights in former colony

-

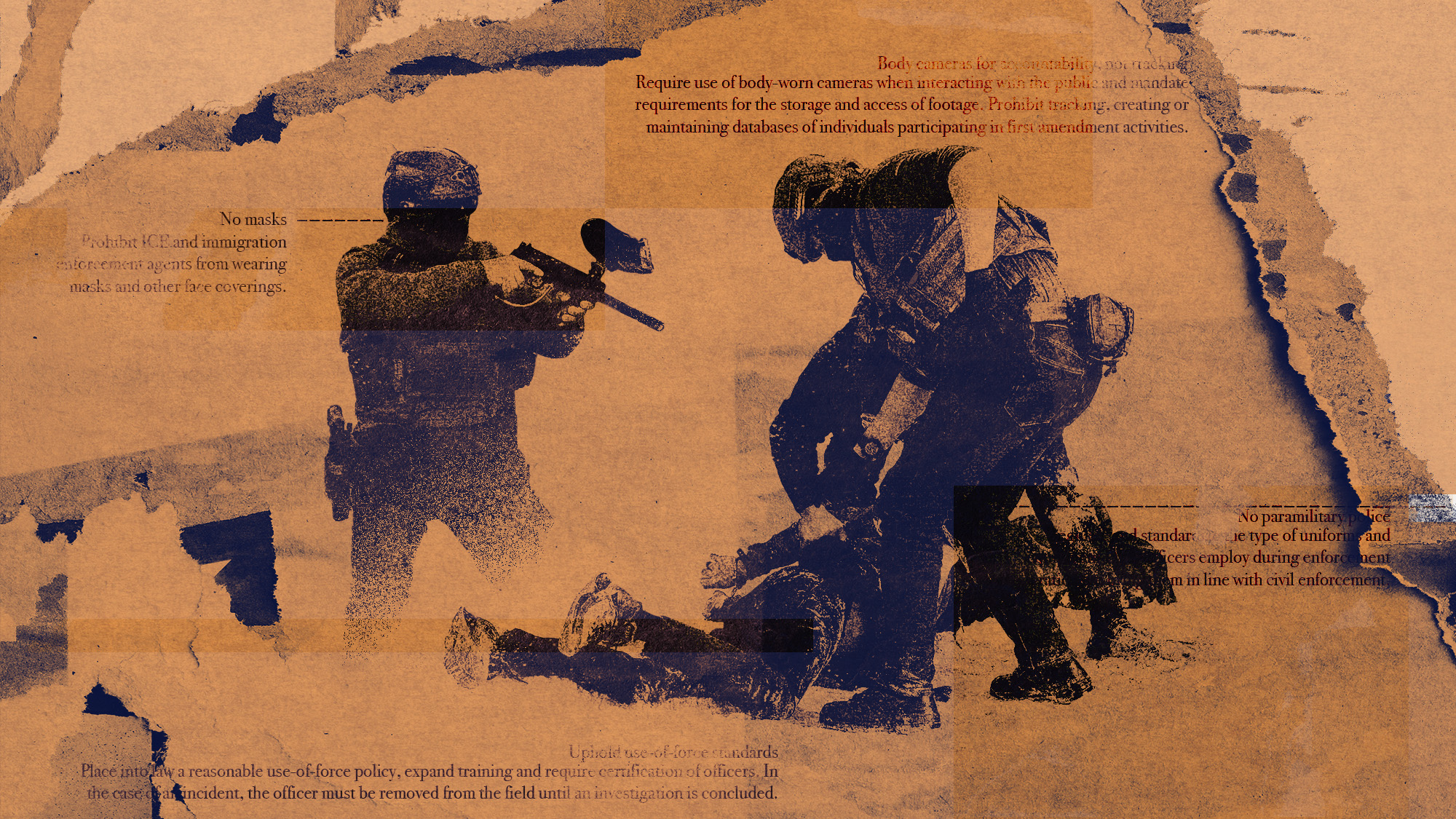

How are Democrats trying to reform ICE?

How are Democrats trying to reform ICE?Today’s Big Question Democratic leadership has put forth several demands for the agency

-

Minnesota’s legal system buckles under Trump’s ICE surge

Minnesota’s legal system buckles under Trump’s ICE surgeIN THE SPOTLIGHT Mass arrests and chaotic administration have pushed Twin Cities courts to the brink as lawyers and judges alike struggle to keep pace with ICE’s activity

-

700 ICE agents exit Twin Cities amid legal chaos

700 ICE agents exit Twin Cities amid legal chaosSpeed Read More than 2,000 agents remain in the region

-

House ends brief shutdown, tees up ICE showdown

House ends brief shutdown, tees up ICE showdownSpeed Read Numerous Democrats joined most Republicans in voting yes