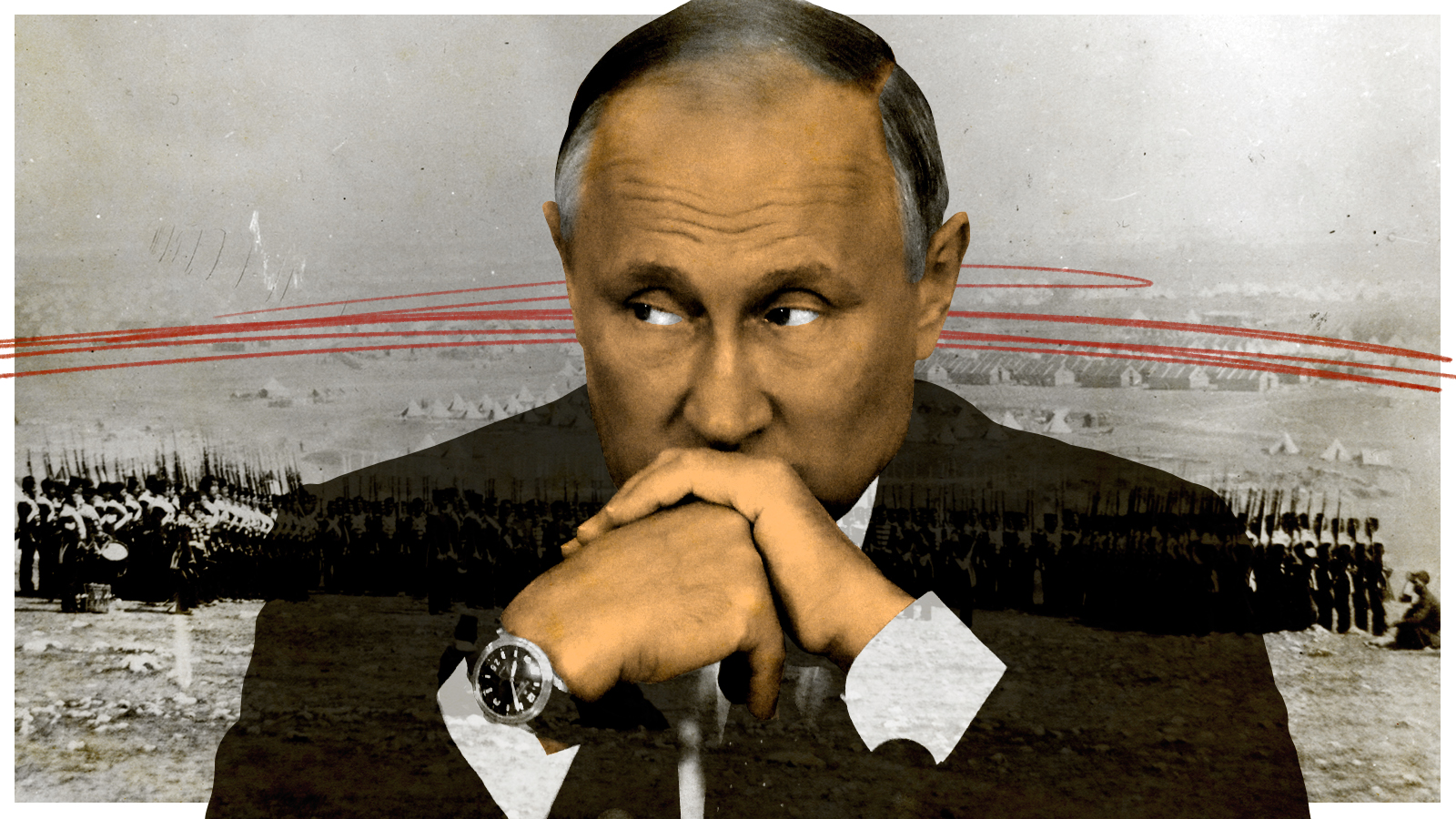

The past is dangerous — if you know how to use it

Putin, Trump, and the irresponsible wielding of history

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Monday's speech by Russian President Vladimir Putin was chilling in several respects — above all, because it used a series of dubious historical assertions to deny the legitimacy of Ukrainian statehood, thereby laying the groundwork for a Russian invasion and conquest of the nation.

But there was something else ominous about the speech, quite apart from any of its specific historical claims. That was its very approach to history — reaching back into the past, dishonestly mobilizing a handful of cherry-picked events for the construction of a story that could be used to motivate decisive action in the present.

Using the past in this way is unthinkable to professional, academic historians and the journalists and intellectuals who rely on, and usually defer to, their work. As children of the Enlightenment, they usually respond to such claims with derision: This is so ignorant. Don't you realize you're butchering the historical record, turning the past into a self-justifying fable? It's propaganda and myth, not authentic history. The truth of the past is so much more complex and so much less useful to your plans than you appear to believe.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The dismissals are usually correct. But they are just as often practically irrelevant. That's because the possession of scholarly credentials doesn't automatically confer the authority to determine which claims about the past will be believed and which will not. On the contrary, fussy objections to the sweeping historical contentions deployed by powerful populist politicians frequently prove impotent in the face of grand narratives.

That leaves critics of these trends with a serious problem.

The philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche wouldn't have been surprised that antiliberal and antidemocratic personalities and movements like to justify their actions by constructing powerful stories about the past that professional historians are quick to dismiss.

Nietzsche distinguished between these very different approaches to the past in a remarkable 1874 essay, "The Use and Disadvantage of History for Life." Trained scholars practice what Nietzsche called critical history — the application of rigorous historical methods to the study of the past in order both to construct the most accurate possible narrative and to puncture less accurate accounts of the past in popular circulation. Think of the scholarship on slavery's ties to the history of capitalism that influenced the "1619 Project" at The New York Times, or of studies that place the Cold War in the context of movements toward decolonization around the globe. The possibilities are nearly endless, capturing just about all the articles and books published by professional historians at any given moment.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Nietzsche contrasted this style of studying the past to what he called monumental history — the use of the past to motivate action by situating the present in the flow of an ongoing story constructed out of various forms of collective meaning. The most responsible forms of monumental history are vaguely hagiographic accounts of great events and figures from the past (usually men) with narratives constructed to inspire patriotic love of country. Presidents and other public figures routinely deploy versions of such civic history to build national cohesion and popular support for various parties and political programs.

Much less responsible examples of monumental history include every anti-Semitic conspiracy theory ever devised, along with a slew of justifications for numerous forms of racism and imperialism. And, of course, there's also Putin's potted history of Russia's relation to Ukraine — a story of the past in which the only evidence adduced advances a predetermined justification for a specific set of potentially murderous policies.

(Nietzsche's essay also delineated a third approach to the past, which he named antiquarian history, the amassing of details about the past for its own sake. This style of history, which one finds enacted at such "living museum" attractions as Colonial Williamsburg, has fewer practical implications for the political present).

Putin is obviously far from the only present-day political actor to deploy monumental history irresponsibly. Donald Trump did it, too, in his inaugural address about "American carnage" and when he talked about the injustice of the U.S. providing security guarantees to other countries without demanding compensatory payment in return. He does the same thing to this day when he insists, without evidence, that he and his supporters were stabbed in the back by the Democrats, the media, and disloyal members of the GOP, who collectively stole the 2020 election from them.

What's most disturbing about these contemporary monumental histories is not that public figures disseminate them but that millions of people find them persuasive. That's troubling because it shows that for many (perhaps most) people, what makes one story about the past more persuasive than another isn't the application of some set of standards approved by a professional guild of scholars but whether the story feels right. If it explains present-day emotions, gives them meaning, and cogently and compellingly assigns blame for various grievances, then it achieves a kind of affective truth.

Perhaps that, more than anything else, explains why so many populist politicians have made so many gains over the past decade around the world. They tell stories that touch large numbers of people, organizing their sense of having suffered an injustice or dishonor, giving it voice and directing the resulting ire and indignation outward, toward clearly delineated targets. For Putin, it's NATO, the U.S. and E.U., Ukraine's Western-leaning government, and anyone else who fails to recognize that Russia is entitled to rule its near-abroad without external interference of any kind.

For Trump, it's Democrats, the media, immigrants, minorities from "sh--hole countries," election fraud, Liz Cheney, and anyone else who fails to demonstrate adequate levels of personal loyalty and deference. (Trump has managed to transmute his demand for personal loyalty and deference into the foundation of his populist appeal by forging an extremely strong bond with his loyal and deferential supporters, who thoroughly trust him and view attacks on him as attacks on themselves.)

In response to these just-so stories, critical historians and their journalistic allies point to errors, exaggerations, the selective use of evidence, and even outright lies — but doing so does little to decrease their popular appeal. That's because, once again, people embrace the stories for their affective power, not for their ability to win the support of specialists flaunting their expertise. Indeed, the very fact that such specialists reject and denounce the stories can lend them added appeal and credibility among nonspecialists.

Where does that leave us? With practitioners of critical history telling admirers of critical history that only critical history is valid, while those who affirm the affective truths of monumental history go right on believing in pernicious mythopoetic constructs?

That is obviously one possibility.

Another would involve partisans of critical history beginning to construct something like a monumental history of their own that demonizes opponents of the rigorous and careful study of the past and valorizes those who aspire to something better — a more complicated and difficult understanding of the past.

In a sense, this would be a profoundly contradictory endeavor, with critical historians potentially working to expose the simplifying pieties of their own efforts at monumental mythmaking. Yet there may be no better way to proceed — by making a powerful, emotionally gripping, but also inevitably somewhat facile case for the importance of understanding the complexly ambivalent character of the past as it really was.

Damon Linker is a senior correspondent at TheWeek.com. He is also a former contributing editor at The New Republic and the author of The Theocons and The Religious Test.

-

Local elections 2026: where are they and who is expected to win?

Local elections 2026: where are they and who is expected to win?The Explainer Labour is braced for heavy losses and U-turn on postponing some council elections hasn’t helped the party’s prospects

-

6 of the world’s most accessible destinations

6 of the world’s most accessible destinationsThe Week Recommends Experience all of Berlin, Singapore and Sydney

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

Epstein files topple law CEO, roil UK government

Epstein files topple law CEO, roil UK governmentSpeed Read Peter Mandelson, Britain’s former ambassador to the US, is caught up in the scandal

-

Iran and US prepare to meet after skirmishes

Iran and US prepare to meet after skirmishesSpeed Read The incident comes amid heightened tensions in the Middle East

-

Israel retrieves final hostage’s body from Gaza

Israel retrieves final hostage’s body from GazaSpeed Read The 24-year-old police officer was killed during the initial Hamas attack

-

China’s Xi targets top general in growing purge

China’s Xi targets top general in growing purgeSpeed Read Zhang Youxia is being investigated over ‘grave violations’ of the law

-

Panama and Canada are negotiating over a crucial copper mine

Panama and Canada are negotiating over a crucial copper mineIn the Spotlight Panama is set to make a final decision on the mine this summer

-

Why Greenland’s natural resources are nearly impossible to mine

Why Greenland’s natural resources are nearly impossible to mineThe Explainer The country’s natural landscape makes the task extremely difficult

-

Iran cuts internet as protests escalate

Iran cuts internet as protests escalateSpeed Reada Government buildings across the country have been set on fire

-

US nabs ‘shadow’ tanker claimed by Russia

US nabs ‘shadow’ tanker claimed by RussiaSpeed Read The ship was one of two vessels seized by the US military