Keep Russian dressing out of your beef with Putin

Dostoyevsky, Swan Lake, and vodka are innocent!

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

In February 2003, as protests against the looming war in Iraq were reaching a peak, a North Carolina businessman decided to put politics on the menu. Provoked by France's opposition to a U.N. ultimatum, Neal Rowland, owner of Cubbie's restaurant in Beaufort, placed stickers that read "Freedom" over the word "French" wherever it appeared. The next month, Congress got into the act: At the behest of Rep. Bob Ney (R-Ohio), the House of Representatives cafeteria began to offer Freedom fries and Freedom toast in place of the more usual descriptions.

The Freedom fries craze entered public memory as an embarrassing symptom of the war fever that gripped America after 9/11. That conflict has become retrospectively unpopular — but we remain susceptible to the same madness.

No one's yet proposed to ban Russian dressing in response to the invasion of Ukraine. Around the country, though, Russian flags have been removed from public display, Russian artists have had engagements canceled, Russian-branded vodka has been removed from shelves (whether or not it's actually produced in Russia), and Russian-themed businesses vandalized.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The situations aren't perfectly analogous. In 2003, France hadn't invaded anyone. To the contrary, its leaders were trying to prevent a war — with good reason, as it turned out. And this time, Americans are far from the only ones losing their minds. A theater in Wales canceled a performance of Swan Lake. An Italian university postponed a class on Dostoyevsky (although the decision was rescinded under heavy criticism). The International Cat Federation has even banned Russian felines from competition.

Yet the urge to eliminate all manifestations of an international rival draws on a current of moralism that runs deep in American culture. During World War I, foods like sauerkraut and frankfurters or wieners were rebranded as "Liberty cabbage" and hotdogs. Towns with Germanic names were rechristened. Pets were swept up in the frenzy then, too: German shepherds and dachshunds came to be known as Alsatians and "liberty hounds," respectively.

Most of these efforts were trivial, although contemporary efforts to suppress the study of the German language were not. Still, they reflect a dangerous temptation to conflate peoples and cultures with governments. That temptation took extreme form recently in a since-deleted tweet by former U.S. Ambassador to Russia Michael McFaul. "There are no more 'innocent' 'neutral' Russians anymore," McFaul said. "Everyone has to make a choice — support or oppose this war." McFaul later claimed that he was echoing Martin Luther King, Jr.'s call to civil disobedience, but his remark was more reminiscent of George W. Bush's insistence that "either you are with us, or you are with the terrorists."

Still, we can admire the courage of Russians protesting the war without denouncing those unwilling or unable to face the immense personal risks as collaborators. We can also reject the suspicious, imperialistic streak in Russian politics without dismissing the culture that produced it as pathological. As the diplomat and foreign policy scholar George Kennan tirelessly argued during the Cold War, Russian strategy has been shaped by a very different set of experiences than those Americans today take for granted — including repeated invasions from the West across the very territory that's now under dispute. That's why Kennan, like many other experts on Russian affairs, opposed the expansion of NATO to include not only members of the defunct Warsaw Pact, but also former parts of the Soviet Union itself.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Whether or not it was a wise decision at the time, NATO expansion is a done deal. Precisely because Russians have to live with a more constrained sphere of influence than they'd prefer, it's essential to reassure them that we don't seek the national destruction that Putin has used to justify aggressive actions in what Russians consider the "near abroad." In addition to avoiding the rhetoric of collective guilt, that means ensuring that economic sanctions don't end up immiserating ordinary people.

Contrary to expectations, making life harder for the population can bind them to the rulers who blame outside interference. Just think of Fidel Castro, Kim Jong Un, or, for a time, Saddam Hussein. And even when sanctions succeed in destabilizing the regimes they target, new dictators may come to power under conditions of economic collapse and social disorder. During World War I, many Americans believed overthrowing the Kaisers and Tsars would ensure a better and more peaceful government in the future. They were wrong.

So far, the Biden Administration has done a good job avoiding hysteria. In his State of the Union address on Tuesday night, the president correctly emphasized that US troops will not be deployed to Ukraine or engage Russian forces. The ostensibly draconian sanctions also include a big loophole for energy, Russia's only major export. Of course, that has more to do with protecting American consumers from inflation than concern about conditions in Russia.

But official policy isn't the only factor in play. The combination of moralistic punditry, institutional virtue signaling, and social media performance can take on a life of its own. In a conflict that may never have a decisive end, that risks boxing the US into inflexible, counterproductive positions. More like the Cold War than World War II, we need to think about the long haul — including the consequences of our Russian policy for relations with other states. That's all the more reason to preserve distinctions between Russia's people, culture, and state rather than collapsing them into an undifferentiated enemy.

Even though it's a vile concoction for which Americans likely hold historical responsibility, don't throw out the Russian dressing just yet. After all, the French are back on our side again, too.

Samuel Goldman is a national correspondent at TheWeek.com. He is also an associate professor of political science at George Washington University, where he is executive director of the John L. Loeb, Jr. Institute for Religious Freedom and director of the Politics & Values Program. He received his Ph.D. from Harvard and was a postdoctoral fellow in Religion, Ethics, & Politics at Princeton University. His books include God's Country: Christian Zionism in America (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2018) and After Nationalism (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2021). In addition to academic research, Goldman's writing has appeared in The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, and many other publications.

-

Labor secretary’s husband barred amid assault probe

Labor secretary’s husband barred amid assault probeSpeed Read Shawn DeRemer, the husband of Labor Secretary Lori Chavez-DeRemer, has been accused of sexual assault

-

Trump touts pledges at 1st Board of Peace meeting

Trump touts pledges at 1st Board of Peace meetingSpeed Read At the inaugural meeting, the president announced nine countries have agreed to pledge a combined $7 billion for a Gaza relief package

-

Britain’s ex-Prince Andrew arrested over Epstein ties

Britain’s ex-Prince Andrew arrested over Epstein tiesSpeed Read The younger brother of King Charles III has not yet been charged

-

The mission to demine Ukraine

The mission to demine UkraineThe Explainer An estimated quarter of the nation – an area the size of England – is contaminated with landmines and unexploded shells from the war

-

The secret lives of Russian saboteurs

The secret lives of Russian saboteursUnder The Radar Moscow is recruiting criminal agents to sow chaos and fear among its enemies

-

Is the 'coalition of the willing' going to work?

Is the 'coalition of the willing' going to work?Today's Big Question PM's proposal for UK/French-led peacekeeping force in Ukraine provokes 'hostility' in Moscow and 'derision' in Washington

-

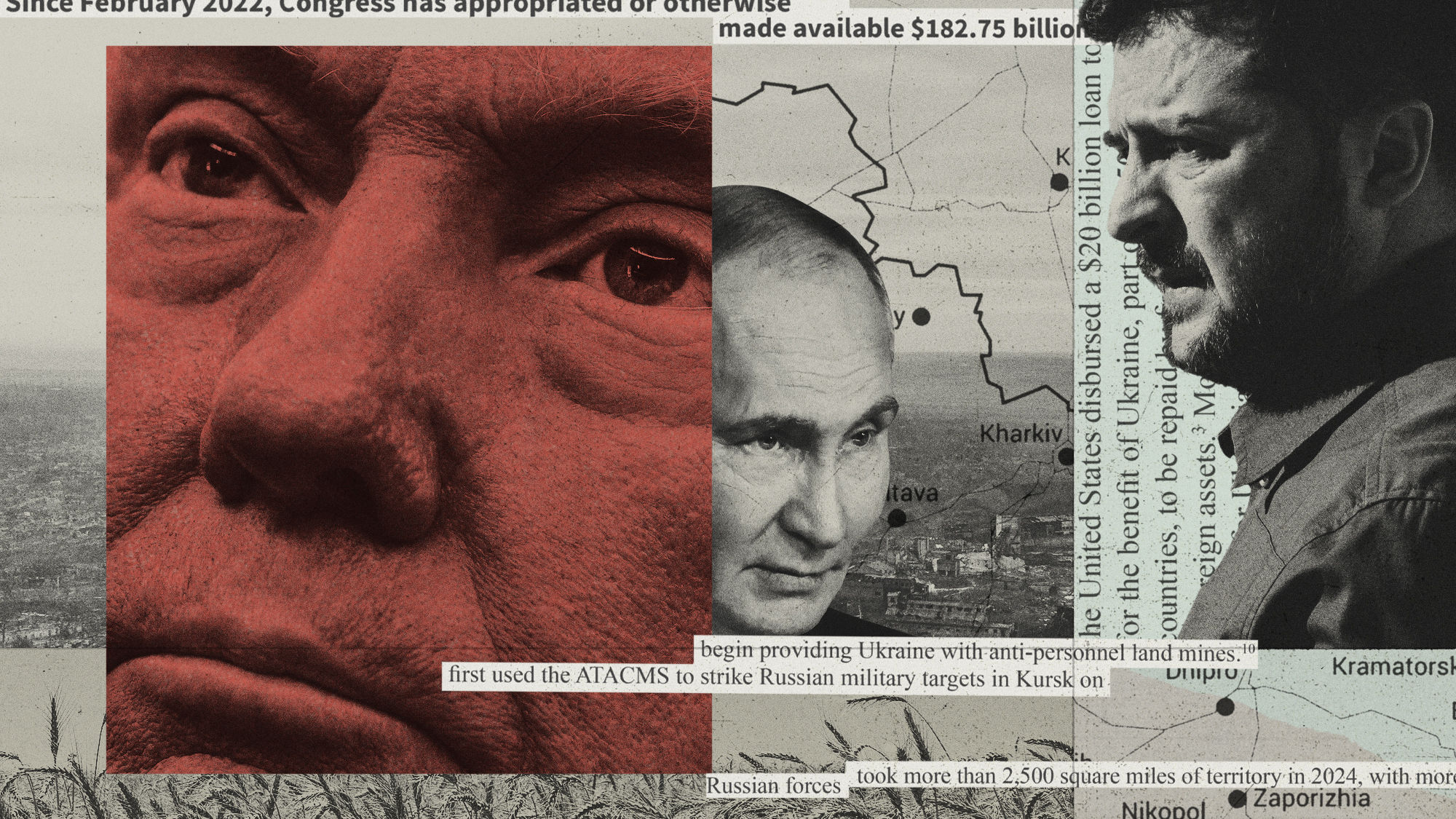

Ukraine: where do Trump's loyalties really lie?

Ukraine: where do Trump's loyalties really lie?Today's Big Question 'Extraordinary pivot' by US president – driven by personal, ideological and strategic factors – has 'upended decades of hawkish foreign policy toward Russia'

-

What will Trump-Putin Ukraine peace deal look like?

What will Trump-Putin Ukraine peace deal look like?Today's Big Question US president 'blindsides' European and UK leaders, indicating Ukraine must concede seized territory and forget about Nato membership

-

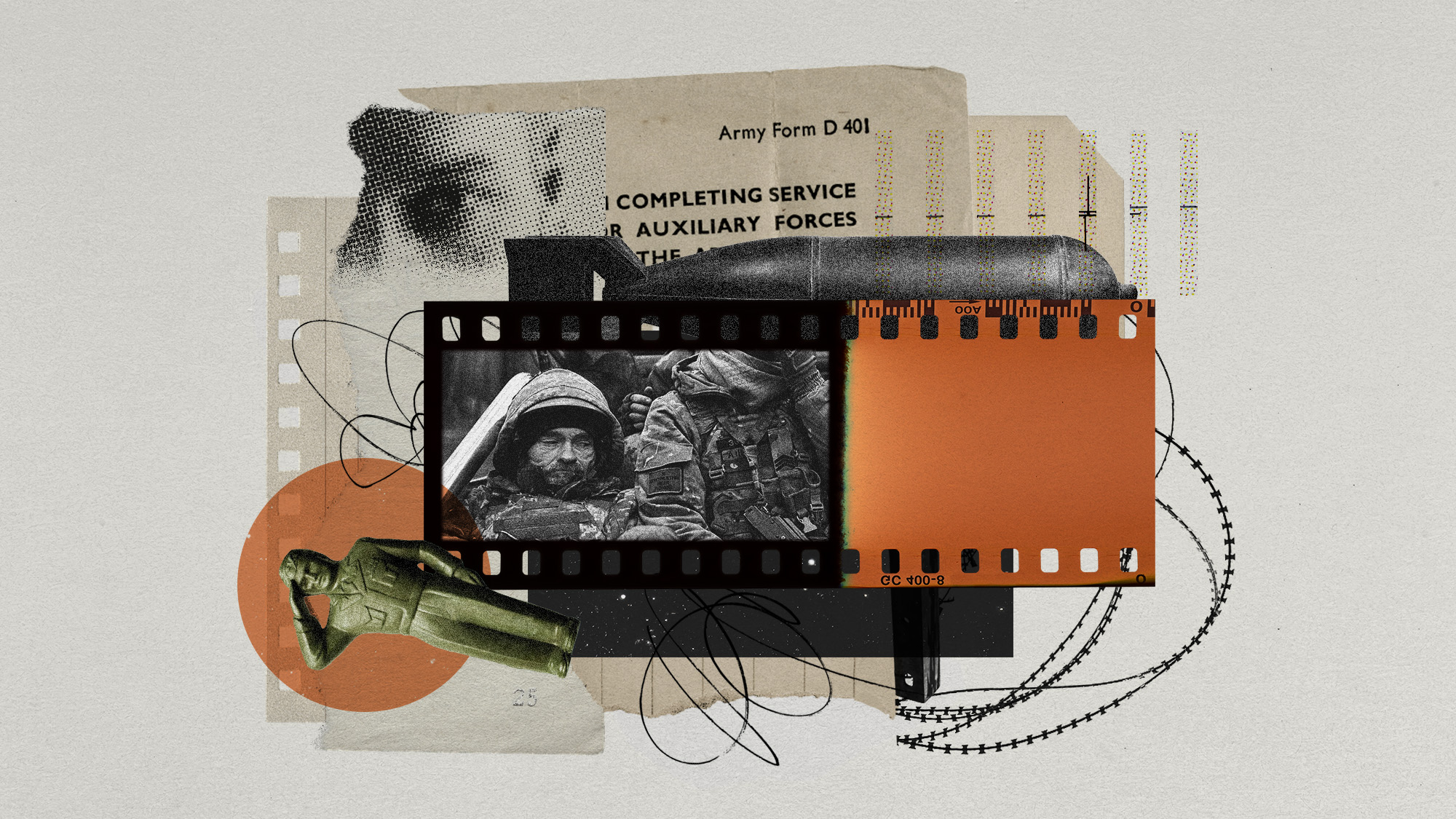

Ukraine's disappearing army

Ukraine's disappearing armyUnder the Radar Every day unwilling conscripts and disillusioned veterans are fleeing the front

-

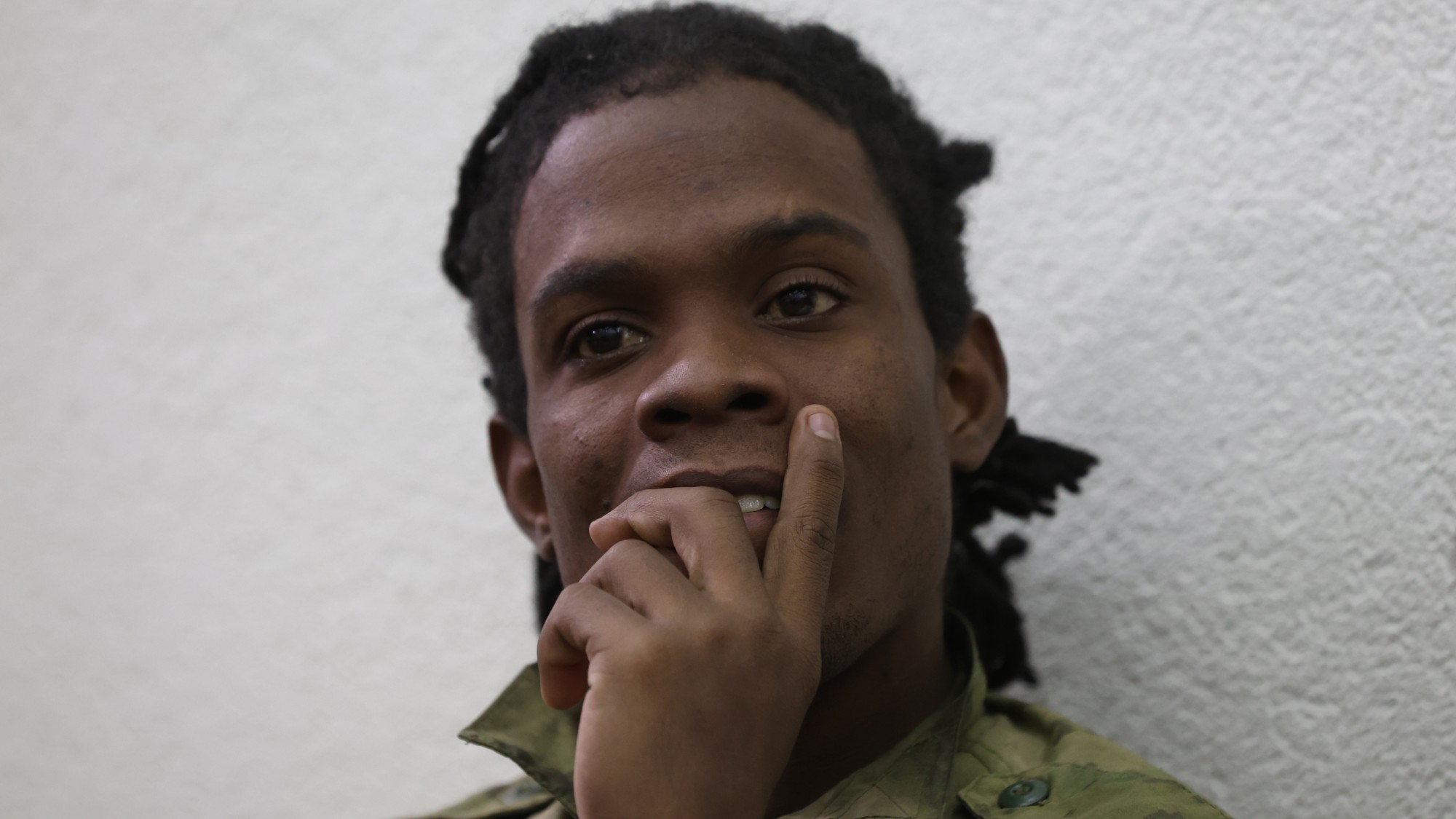

Cuba's mercenaries fighting against Ukraine

Cuba's mercenaries fighting against UkraineThe Explainer Young men lured by high salaries and Russian citizenship to enlist for a year are now trapped on front lines of war indefinitely

-

Ukraine-Russia: are both sides readying for nuclear war?

Ukraine-Russia: are both sides readying for nuclear war?Today's Big Question Putin changes doctrine to lower threshold for atomic weapons after Ukraine strikes with Western missiles