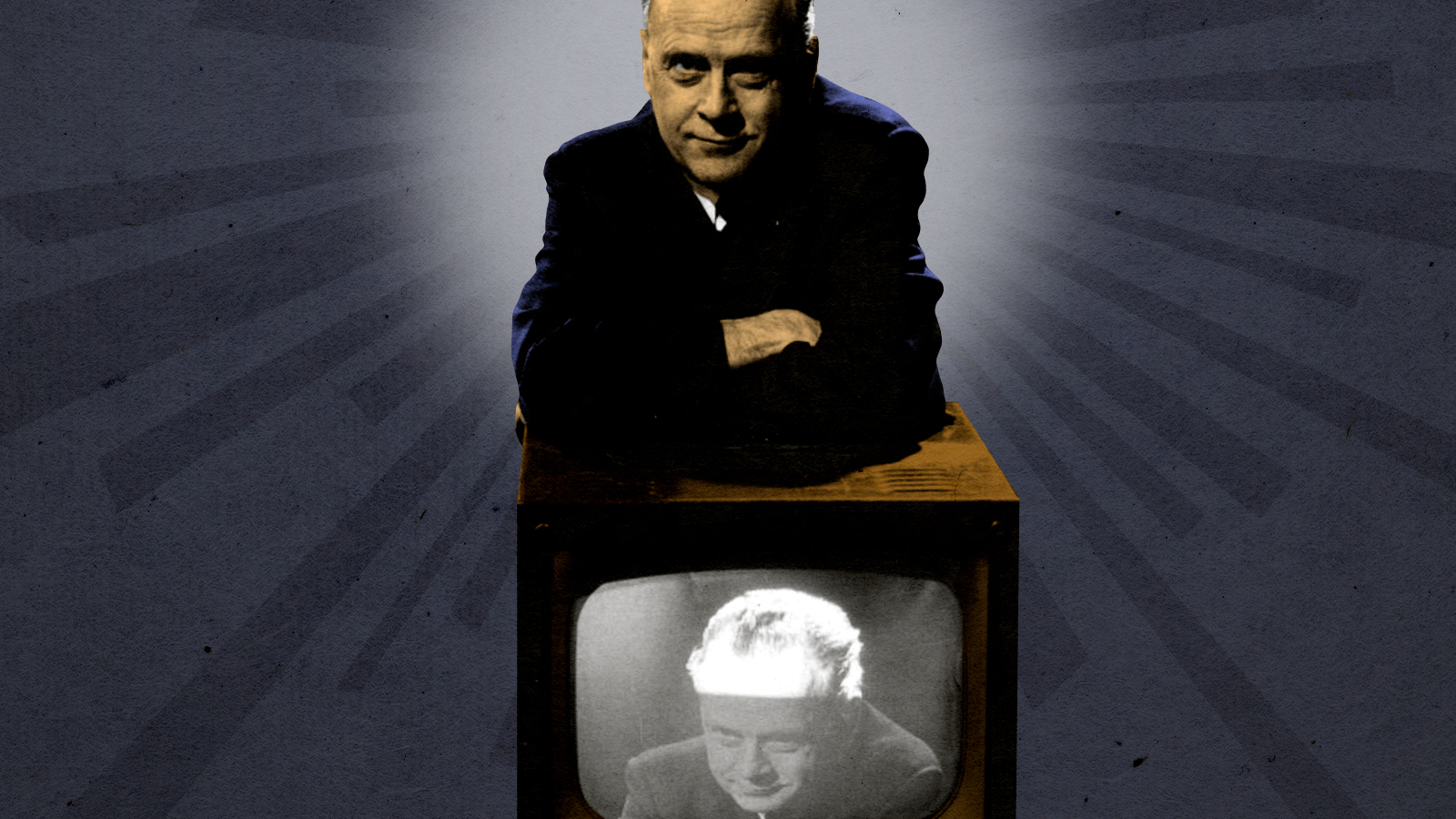

A new medium for Marshall McLuhan's message

Why a 1960s rockstar intellectual means even more in the digital age

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Recently a BBC researcher joined VRChat, an app available via Facebook's Meta Quest headset — and saw harassment and a rape threat.

"Horrible. It was strange. It felt like it was happening to me."

The seedy, toxic environment had no age verification checks; the researcher posed as a 13-year-old-girl, and "grown men were asking me why I wasn't in school and encouraging me to engage in VR sex acts." In this and other fully virtual environments, the human body — and morality — is often tossed aside.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Marshall McLuhan worried such a thing would happen. More than 50 years ago, he warned that eventually, there will be "the shaping, the twisting, the bending of the whole human environment by the technology." He thought a transformation was coming: "we approach the final phase of the extensions of man — the technological simulation of consciousness." We become the machine.

If you've never heard of McLuhan, join the club: the quirky 20th century media theorist is now mostly known for his aphorisms — "the global village," "the medium is the message"—rather than his actual life.

Yet McLuhan experienced an incredible span of popularity in the 1960s and 70s: he was profiled or featured in Vogue, Playboy, Harper's, The New York Times, Mademoiselle, Time, Fortune, Life, Newsweek, The New Yorker, Look, the Los Angeles Times, and Esquire. NBC featured an hour-long documentary on McLuhan, helmed by two Oscar-winning directors.

He appeared on The Today Show and The Tomorrow Show, and on The David Frost Show alongside actor Peter Fonda. He debated contemporary novelist Norman Mailer several times. Goldie Hawn's occasional line on the comedy show Laugh-In was "Whatcha doin', Marshall McLuhan?" a line John Lennon quipped when he and Yoko Ono sat for an interview with McLuhan.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

In short, McLuhan was everywhere someone could be and far more places than anyone expected an intellectual might be.

Then the popular and critical backlash started. Academics scoffed at the absence of footnotes and indexes in his books, and didn't appreciate his frequent media appearances. He befuddled his critics. McLuhan was a Canadian-born Cambridge PhD with a dissertation on 16th century satirist Thomas Nashe and the classical trivium, but was holding forth about the coming electronic world and speaking in riddles: "In television, images are projected at you. You are the screen. The images wrap around you. You are the vanishing point." Seen as more of a carnival barker than a public scholar, he passed from favor.

We should take another look at McLuhan — now that his worst fears are being realized. Sixty years ago, McLuhan published his second book, The Gutenberg Galaxy: The Making of Typographic Man.

Johannes Gutenberg, McLuhan wrote, "made all history simultaneous" yet he also upended traditional communication. Oral storytelling, for McLuhan, stimulated the full imagination. When our ears alone receive the story, our mind offers the story its imagery.

The creation of the phonetic alphabet, in contrast, forced our eyes to do the work. Letters and words are not things; they are signs toward things. We have become accustomed to such signs, but McLuhan reminds us that our alphabet "dissociates or abstracts, not only sight and sound, but separates all meaning from the sound of the letters, save so far as the meaningless letters relate to the meaningless sounds."

Gutenberg's print fragmented our senses. The electronic world — radio, television, film — patched us together. Electronic media required that our senses "now constitute a single field of experience which demands that they become collectively conscious."

His prose was packed and dense — and his critics were correct that he could be confusing. Yet they misunderstood that McLuhan was a performer; like his mother, a traveling elocutionist, McLuhan followed the poetic routes of his sentences. He was equal parts discursive and recursive. No matter one's medium, McLuhan said the "business of any performer" is to "put on the audience, not speak to the audience."

Yet McLuhan's put-ons were not mere fluff. As brilliant as he was bombastic, McLuhan was also deeply religious a Catholic convert who viewed the world as always on the brink of communion. This largely ignored element of his life helps illuminate his theories.

The oft quoted "the medium is the message" is typically used as shorthand for claiming that the media through which we communicate (television, phone) are more important than their content.

McLuhan found it necessary to clarify his famous dictum: "It really means a hidden environment of services created by an innovation, and the hidden environment of services is the thing that changes people. It is the environment that changes people, not the technology."

To my cradle Catholic ears, that sounds downright spiritual in its formulation.

As early as 1963, McLuhan was observing that "electronic media" are "extensions of the central nervous system, an inclusive and simultaneous field."

Whether we are watching television or even driving a car, our participation in the mechanical-electronic world conforms to the structure and requirements of that world so that "we become servo-mechanisms of our contrivances, responding to them in the immediate, mechanical way that they demand of us."

Forget the old Narcissus myth of a love of our own image, we now "fall in love with extensions" of ourselves which we "are convinced are not extensions." The phenomenon was concerning in McLuhan's mechanical world; in our digital world, it is nightmarish.

"Contracted" by electronics, McLuhan wrote, "action and reaction occur almost at the same time." Our identity is malleable: "Everything under electric conditions is looped. You become folded over into yourself. Your image of yourself changes completely."

The more online we are, the more these quasi-mystical statements feel precise. McLuhan's statements predate the internet, so is it fair to apply his descriptions of the electronic world to the digital one? I think so.

McLuhan feared a fully electronic (now digital) space in which the human body is mere vessel, tossed aside. Even though McLuhan was nervous about the evolution of television and other media, he knew that our physical bodies still anchored us in the real. If we fully embrace digital or virtual reality spaces without the proper accountability and protection, especially for the most vulnerable — there is nothing to root us.

McLuhan would argue that we need to protect ourselves, and, in his religious vision, to protect our souls. In his third book, Understanding Media, he quoted a 1950 speech from Pope Pius XII: "It is not an exaggeration to say that the future of modern society and the stability of its inner life depend in large part on the maintenance of an equilibrium between the strength of the techniques of communication and the capacity of the individual's own reaction."

The metaverse and similar virtual spaces, without proper moderation, threaten to extinguish the self. Media are no longer extensions of our body (as McLuhan described) — such media now subsumes the body.

Critics of McLuhan have cataloged the moments when his predictions missed or when his rhetoric smothered his reason. His aphoristic observations could sometimes sound trite, especially when examined through our contemporary mode of cynicism. The internet is often a profoundly pessimistic place: a repository for conspiracy theories that have developed into metanarratives, a place where anonymous avatars troll and tussle with abandon. In many ways, the space of the internet cultivates and rewards skepticism — which means a literature professor turned media theorist was a most unlikely prophet.

This was McLuhan's power, in a sense: he was not supposed to have figured all of this out. In 1966, McLuhan told Tom Wolfe that in every "organization, each individual tends to have a point of view. The consultant who is called in to diagnose has the advantage of not having a point of view."

We might consider McLuhan a cultural consultant. He was outdated and outmoded during his own time, his identity a dramatization of tension between that which is obsolete and obsolescent. Yet now he fits perfectly into our digital present; McLuhan's mosaic method of disjointed interpretation matches our harried lives, and his fears have become our realities.

Marshall McLuhan is a man for our time.

Nick Ripatrazone is the Culture Editor for Image Journal, and has written for Rolling Stone, The Atlantic, GQ, and Esquire. His latest book is Digital Communion: Marshall McLuhan's Spiritual Vision for a Virtual Age (Fortress Press 2022).