'Why are there no girl presidents?' A response to my daughter.

Traditional explanations from the left and the right both fall short

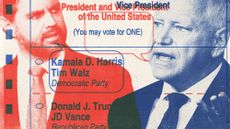

Twice in the past few months, my precocious nine-year-old daughter has come home from school a little down. Why, she wonders, has every single American president been a man? Why have none of them been a woman?

That America's uninterrupted 226-year string of 44 male presidents strikes my daughter as surprising and inexplicable nicely confirms that my wife and I have managed to create a pretty thoroughly egalitarian household. From the time my daughter learned to communicate, she's heard nothing except a message of equality, and had nothing but equality modeled for her. I work. Her mom works. I have a demanding, high-profile job. Her mom has a demanding, high-profile job. I'm the main caregiver on some days. She's the main caregiver on other days.

We also share the burdens and joys of running the household. I cook most of the dinners. My wife does most of the laundry. I usually load the dishwasher. She usually unloads it. And so forth. There is nothing overtly gendered about the division of labor that prevails in our home, just as there is no academic subject or hobby or career path that has been foreclosed to my daughter because she's a girl.

Subscribe to The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

All of which is great. Except for the cold hard slap of reality that she faces when she leaves our home — the first taste of which is a third-grade lesson in American political history.

So why have there been only "boy presidents"?

Answering that question is trickier than you might think — at least for me.

If I were a traditionalist conservative, it would be easy. I'd simply say, "All American presidents have been men because boys are good at certain things, and girls are good at other things, and politics is one of the things boys do better. Don't feel bad. The things girls are good at — having babies, caring for them, running the domestic (private) sphere — are very important. But that's a different set of skills than the very public virtues we require from a president."

If I were a leftist, it would be similarly easy. I'd simply say, "All American presidents have been men because America is part of Western civilization, and Western civilization has been thoroughly sexist from the beginning. Only in the past couple of generations have women finally, at long last, begun to throw off the oppressive yoke of male domination. It's no wonder that there's never been a female president, given this tainted history of male hegemony."

But I'm neither a conservative who wants to uphold traditionalist gender roles nor a leftist who wants to throw all of Western civilization and American history onto the sexist scrap heap.

I'm a feminist, a liberal, and an American patriot. I want my daughter to be treated as an equal, but I also want her to love her country and view its history with admiration, understanding, and sympathy.

That's why, once she gets a few years older, I plan to say something like the following when she once again poses the question about America's run of all-male presidents:

Human beings have existed for about 200,000 years. For almost all of that time, life has been a horrible struggle against scarcity. Through millennia of hunting and gathering, and more recent times of agricultural settlements and cities, the vast majority of human beings have scraped by, toiling most of their lives for food, shelter, clothing, and other basic necessities of existence.

In such circumstances, it made sense for families to develop a strict division of labor based on the single most significant natural differences between the sexes: the greater size and physical strength of the male (on average), and the singular capacity of women to bear children. Men would take the lead in providing, protecting, hunting, and plowing the fields while women would care for the young children and tend to life in the home, while also helping with other tasks as needed.

Nearly every cultural form of male domination followed from the prehistoric gendered division of labor. This included political activity and engagement reserved almost exclusively for men, along with elaborate religious and philosophical accounts (nearly always written by men) of the proper (distinct but complementary) social roles for men and women. Before long, a historically contingent, evolutionary holdover from a time of bare material survival had mixed with human reason and imagination to produce a profoundly gendered — but also often beautifully intricate and intellectually formidable — spiritual-cultural vision of reality in which those contingencies appeared to be necessary and even deliberately intended by nature, God, or both.

America's uninterrupted line of male presidents can be traced back to this still strong spiritual-cultural inheritance. At least since the time of the 18th-century Enlightenment, with its call to subject received norms, practices, and beliefs to critical scrutiny, the Western world has had the intellectual tools to dismantle elements of this inheritance that seem not to comport with justice and our experience of the world. And since roughly the mid-19th century in the United States, that sense of justice and experience has increasingly clashed with the received stories about how men are better suited to politics than women.

What changed? Many things, including the democratic leveling of hierarchies in other spheres of life and the moral self-assertion of women and their demand to be treated as equals. But perhaps most significant of all has been the end of the material scarcity that led prehistoric humans to adopt a gendered division of labor in the first place. Despite the persistence of relative poverty in many places, and hunger and other forms of deprivation in many others, vast swaths of humanity now live in a condition of abundance that would have been unimaginable in past ages.

It is this abundance, this overcoming of scarcity, that has allowed us to begin kicking free of the old gendered division of labor. Not that gender roles have been completely scrambled. Many more American women than men choose to take the lead in caring for young children, for example. Maybe this would change if the law required employers to provide generous benefits to new fathers. But then maybe the law would require employers to provide generous benefits to new fathers if voters demanded it. That they don't is yet another sign of the persistence of the old ways.

This, or something very much like it, is what I plan to tell my daughter — that our highly gendered cultural inheritance combines much that is beautiful with much that is unjust, and that we're still disentangling what we hope to preserve from what we want to cast aside. As part of that process, more and more women are rising to positions of political (and economic and cultural) power.

And someday soon (maybe even before my daughter is old enough to have this very conversation) one of them is bound to become the first female president.

Sign up for Today's Best Articles in your inbox

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Damon Linker is a senior correspondent at TheWeek.com. He is also a former contributing editor at The New Republic and the author of The Theocons and The Religious Test.

-

The mental health crisis affecting vets

The mental health crisis affecting vetsUnder The Radar Death of Hampshire vet highlights mental health issues plaguing the industry

By Chas Newkey-Burden, The Week UK Published

-

The Onion is having a very ironic laugh with Infowars

The Onion is having a very ironic laugh with InfowarsThe Explainer The satirical newspaper is purchasing the controversial website out of bankruptcy

By Justin Klawans, The Week US Published

-

'Rahmbo, back from Japan, will be looking for a job? Really?'

'Rahmbo, back from Japan, will be looking for a job? Really?'Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

By Justin Klawans, The Week US Published

-

US election: who the billionaires are backing

US election: who the billionaires are backingThe Explainer More have endorsed Kamala Harris than Donald Trump, but among the 'ultra-rich' the split is more even

By Harriet Marsden, The Week UK Published

-

US election: where things stand with one week to go

US election: where things stand with one week to goThe Explainer Harris' lead in the polls has been narrowing in Trump's favour, but her campaign remains 'cautiously optimistic'

By Harriet Marsden, The Week UK Published

-

Is Trump okay?

Is Trump okay?Today's Big Question Former president's mental fitness and alleged cognitive decline firmly back in the spotlight after 'bizarre' town hall event

By Harriet Marsden, The Week UK Published

-

The life and times of Kamala Harris

The life and times of Kamala HarrisThe Explainer The vice-president is narrowly leading the race to become the next US president. How did she get to where she is now?

By The Week UK Published

-

Will 'weirdly civil' VP debate move dial in US election?

Will 'weirdly civil' VP debate move dial in US election?Today's Big Question 'Diametrically opposed' candidates showed 'a lot of commonality' on some issues, but offered competing visions for America's future and democracy

By Harriet Marsden, The Week UK Published

-

1 of 6 'Trump Train' drivers liable in Biden bus blockade

1 of 6 'Trump Train' drivers liable in Biden bus blockadeSpeed Read Only one of the accused was found liable in the case concerning the deliberate slowing of a 2020 Biden campaign bus

By Peter Weber, The Week US Published

-

How could J.D. Vance impact the special relationship?

How could J.D. Vance impact the special relationship?Today's Big Question Trump's hawkish pick for VP said UK is the first 'truly Islamist country' with a nuclear weapon

By Harriet Marsden, The Week UK Published

-

Biden, Trump urge calm after assassination attempt

Biden, Trump urge calm after assassination attemptSpeed Reads A 20-year-old gunman grazed Trump's ear and fatally shot a rally attendee on Saturday

By Peter Weber, The Week US Published