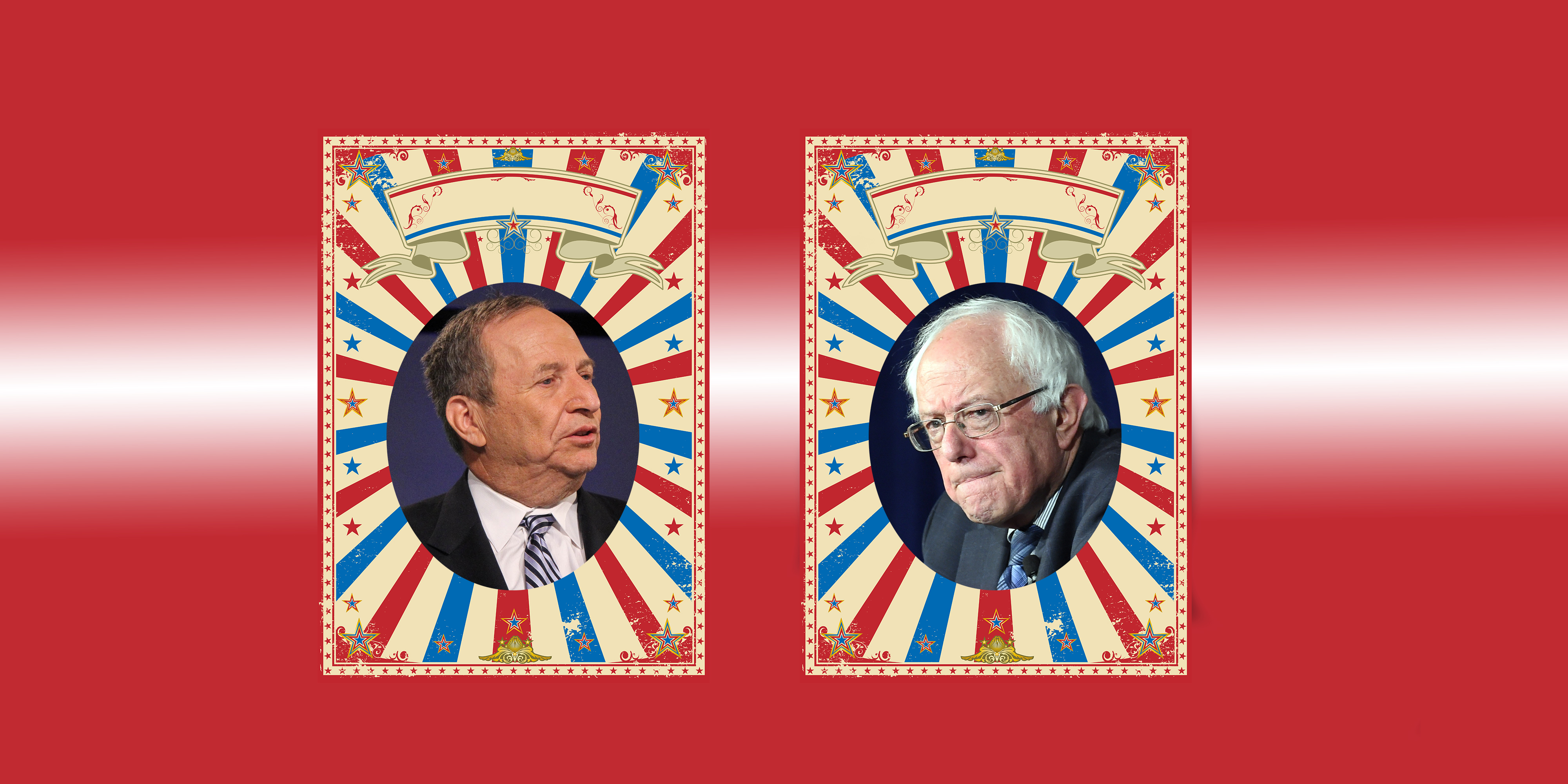

Larry Summers' debate with Bernie Sanders over the Fed, explained

The former treasury secretary and the socialist senator agree more often than you'd think

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Stop the presses! Bernie Sanders and Lawrence Summers seem to basically agree on the need to reform the Federal Reserve.

Sanders, as you may know, is the self-identified democratic socialist running for the Democratic presidential nomination. Summers was a treasury secretary under Bill Clinton and a major economic advisor to President Obama — but lots of lefty Democrats don't like him (to put it very mildly) because of his role in Clinton's centrist economic policies and financial deregulation. So the fact that both Sanders and Summers wrote op-eds recently sounding similar notes on what to do about one of the country's most rarified and mysterious economic policymaking institutions is something to sit up and take note of.

But if, unlike me, you're a sane a well-adjusted human being with a regular day job and interests in normal things like sports and gardening and what not, your eyes probably glaze over when people say things like "Federal Reserve" and "monetary policy." So here's a simple and stripped-down guide to the Federal Reserve, what it does, how we might reform it, and where Sanders and Summers agree and where they don't.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

At the most basic level, the Fed's job is control the supply of money in the economy. Think of it this way: If you had an island with 100 people and just 100 dollars, it would be really hard for the island's economy to function. That limited supply of dollars would severely limit how much you could pay people for jobs or charge them for goods and services. So someone has to oversee that supply, and make sure it keeps pace with the economy's needs. That's the Fed.

The Fed has lots of tools for raising or lowering the supply of money in the economy. Most people are familiar with its influence over interest rates: The Fed raises them to shrink the money supply and lowers them to boost it. But whether it's interest rates or interest on reserves or experimental stuff like quantitative easing, expanding or contracting the supply of money is what it boils down to.

Some of the Fed's tools add money to the economy directly, while some of them influence the banking system to release more or less money from individual banks. For an example of the latter, the Fed pays banks interest for reserves they keep stored at the Fed, which Sanders is not happy about. But as Summers noted, this is a perfectly legitimate tool for encouraging the banks to stash away reserves and thus shrink the money supply. It's just a question of whether shrinking the supply is what the Fed should be doing right now.

Because the Fed is caught in a balancing act: Increase the money supply too much, and you get inflation. Decrease it too much, and you choke off credit, which chokes off job and wage growth.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

That's why when Congress created the Fed, it gave it a dual mandate: "maximum employment" and "stable prices." But how to thread the needle between those two obligations is up to the Fed's decision-making body: the Federal Reserve's Open Market Committee (FOMC). The FOMC has 12 voting members — seven are appointed by the president and confirmed by the Senate, the other five are drawn from the presidents of the Fed's regional branches on a rotating basis. These regional presidents, in turn, are appointed to their positions by nine-member committees — three drawn from the banking sector, three drawn from the private sector, and three drawn to represent the public interest. There are also another five non-voting members of the FOMC who participate in the group's debates, and are also drawn from regional banks.

This gets to the big thing that Sanders and Summers agree on: The financial industry and private business enjoy far too much influence on the Fed's governing structure.

The Dodd-Frank financial reform bill already cut the three banking sector representatives on the regional committees out of the process of appointing regional presidents, and Summers allows that it's not clear why three positions should be reserved for the private sector either.

Sanders wants to go further and have each regional president appointed by the president and approved by the Senate. Summers is more hesitant on that point. But one way to split the difference here could be to simply cut the regional presidents out of the FOMC's decision-making process — make everyone who votes on Fed monetary policy accountable to the Democratic process by putting them through the nomination and confirmation process. (And get the non-voting members out of the FOMC, too.) Activists and voters could then apply political pressure to ensure FOMC members are drawn, per Sanders, "from all walks of life."

How to reform the governance of the regional banks is murkier. But one thing worth mentioning is that simply making sure voters and activists pay attention to the process, are kept informed of what's going on, and are permitted to offer public comments, would be a big change in itself, and could alter the character of the regional branches.

That brings us to the final question of rules-based monetary policy.

The Fed's dual mandate gives it no hard numerical targets for what constitutes "stable inflation" or "maximum employment." This introduces the possibility of human error and bias. And the financial and business elites who hold disproportionate influence at the Fed have far more self-interest in keeping inflation low than in keeping the jobs supply up.

The FOMC itself has essentially picked 2 percent as its inflation target, but in practice it's behaved more as if it were a ceiling. Both Sanders and Summers have criticized the Fed's recent decision to raise interest rates. And if you look at recent history, the Fed's generally done a very good job of keeping inflation stable, but a very bad job of maximizing employment.

Sanders argues the Fed shouldn't even think about raising interest rates until unemployment is 4 percent or lower. And again, there's plenty of historical evidence that the FOMC has consistently underestimated how low unemployment can go before inflation becomes a danger.

Summers is not so keen on a hard and fast rule. Many of the most prominent politicians advocating a rules-based monetary policy are calling for a gold standard or a pure inflation target. In other words, they would force the Fed to concentrate even more on fighting inflation and less on boosting employment than it already does. Summers clearly worries about giving them any openings.

But not all monetary rules are created equal. A gold standard would clearly be disastrous, as it would force the Fed to perpetually keep the money supply too small. Something like the Taylor rule would not be much better. But something like nominal gross domestic level targeting would arguably have forced the Fed to tolerate considerably more inflation than it has over the last few decades.

The devil will be in the details. General readers can dig into those if they like. But what should concern them is how a rule would strike the balance between keeping inflation under control and maximizing job and wage growth.

Because that's really the issue, and the primary thing to remember is that the Fed has been failing on the job and wage side for years. Maybe we solve that by making the Fed more democratically accountable. Or maybe we can solve it by reducing subjective human decision-making in the process in favor of a stricter rule.

But what we need — and what both Sanders and Summers are calling for — is a Fed that focuses more on the needs of everyday workers, and less on the needs of wealthy elites.

Jeff Spross was the economics and business correspondent at TheWeek.com. He was previously a reporter at ThinkProgress.

-

The problem with diagnosing profound autism

The problem with diagnosing profound autismThe Explainer Experts are reconsidering the idea of autism as a spectrum, which could impact diagnoses and policy making for the condition

-

What are the best investments for beginners?

What are the best investments for beginners?The Explainer Stocks and ETFs and bonds, oh my

-

What to know before filing your own taxes for the first time

What to know before filing your own taxes for the first timethe explainer Tackle this financial milestone with confidence

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred