How Trump's CNN feud could wreck antitrust reform

It would actually be a great thing if regulators squashed the Time Warner-AT&T deal. But now it will inevitably be tainted by the suspicion that Trump is punishing his opponents.

In the American economy, size increasingly matters.

In 1994, revenue for the Fortune 500 companies made up 58 percent of the economy; by 2013, it was 73 percent. Mergers and acquisitions are speeding up, with 2015 hitting new heights and 2016 likely surpassing it. Companies like Facebook, Apple, Google, Amazon, and Walmart increasingly dominate their respective markets. Meanwhile, income inequality is soaring, while wages and jobs remain underwhelming even after eight grinding years of recovery.

All this suggests antitrust law is in need of a massive overhaul. That's the web of statutes enforced by a few government agencies — mainly the Justice Department and the Federal Communications Commission — aimed at promoting competition and preventing monopolies.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Unfortunately, President Trump's intensifying feud with CNN might screw it all up.

Their disagreements predate Trump's presidency. The network dropped a bombshell report in January on a dossier compiled by British intelligence regarding some particularly salacious possible connections between Trump and Russia, angering the then-president-elect. Since then, CNN has also had two embarrassing episodes where a story on the White House had to be either corrected or retracted entirely — leading to the resignation of three reporters in the latter instance. There might also be a personal dimension to the feud: Jeff Zucker, now the president of CNN, hired Trump to host The Apprentice back when he was at NBC. And Trump now takes credit for Zucker going on to head up CNN. Zucker suggested to The New York Times that the president might view the network's negative coverage as betrayal.

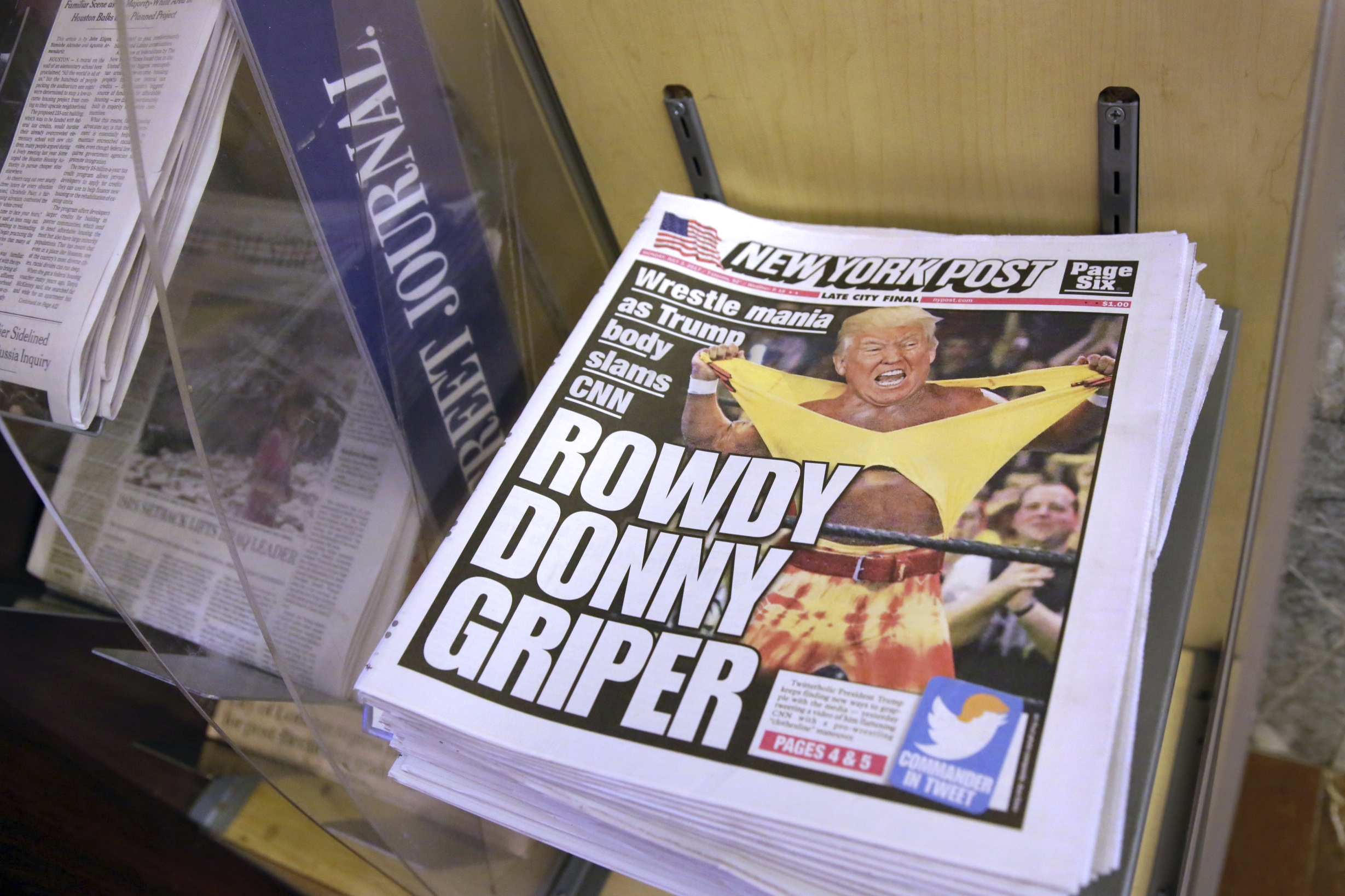

At any rate, CNN now finds itself at the center of a Trumplandia backlash. The whole thing culminated a few days ago when President Trump tweeted a doctored video of himself "beating up" CNN's logo at a wrestling event.

It was very silly. But there is a way that the very serious matter of antitrust law could wind up getting sucked into this circus.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

CNN is owned by Time Warner, which is set to be bought by AT&T. The merger comes under the jurisdiction of antitrust law, so federal regulators will have to sign off on the deal. "White House advisers have discussed a potential point of leverage over [CNN]," a senior administration official told the Times. "And while analysts say there is little to stop the deal from moving forward, the president’s animus toward CNN remains a wild card."

Basically, Trump might use antitrust enforcement as a weapon to punish CNN's parent company for its coverage of him.

The Atlantic's David Frum actually raised this possibility back in March, as an example of how Trump could bully major corporations and media companies into cooperating with his agenda and policies, thus pushing the country down the road to autocracy. And even though it's not clear how serious the White House is about this idea, that they're even raising the possibility creates a godawful mess.

That's because it would actually be a great thing if regulators reversed course and squashed the Time Warner-AT&T deal: It would signal a return to an older and more vigorous approach to antitrust enforcement that the country desperately needs. But now, if regulators did make such a choice — or got serious about other antitrust enforcement for the remainder of Trump's administration — it will inevitably be tainted by the suspicion that the president is punishing his opponents. (Or rewarding supporters by not scuttling a merger.)

The trouble is that antitrust enforcement is inherently political — or at least it should be, if it's to function properly.

Back when it used to work, antitrust enforcement was rooted in a set of subjective political values: The belief that local economic decisions should be controlled by local actors; that our economics should be as democratic as our politics; that domination of the economy by a small set of super-companies was poisonous to society; and that the market should be roughly egalitarian so all Americans could try their luck in it. As a result, antitrust enforcement was extremely strict. It banned vertical integration and prevented any single company from taking over even modest market share.

But in the 1980s, a new approach swept all that away by "rationalizing" this subjective criteria. Instead of investigating how a merger would affect society, its only concern was whether a merger was likely to raise prices for consumers. If the answer to that question was "no," courts and regulators generally allowed a merger. Needless to say, this approach didn't work — it's exactly what led to our current impasse.

So reform will require everyone to admit that subjective moral and political judgments should play a key role in antitrust law. But if Trump successfully associates "subjective political judgments" with his own bullying strong-arming, he could sully the whole process. The temptation among many elites to retreat back into the fantasy of an "objective" approach to antitrust law will be overwhelming.

To guard against this possibility, advocates of reform should start thinking harder about what they want the new antitrust regime to look like. They should draw up a list of guidelines and principles: A specific threshold for market share that no company should be allowed beyond, and rules of thumb for judging the shape and scope of the market in question. It should include rules for preventing vertical integration. It should include specific criteria for how to assess local ownership and control, as well as how to measure the vibrancy of competition in a given market — and it should lay out hard goals for all of those metrics.

Such a policy platform can and should be guided by those higher moral and political concerns: democracy, localism, decentralization, and giving every market entrant a fair shake. But if they're to survive the Trump era, those values need to be embedded in clear rules that everyone should be expected to follow.

Jeff Spross was the economics and business correspondent at TheWeek.com. He was previously a reporter at ThinkProgress.

-

7 bars with comforting cocktails and great hospitality

7 bars with comforting cocktails and great hospitalitythe week recommends Winter is a fine time for going out and drinking up

-

7 recipes that meet you wherever you are during winter

7 recipes that meet you wherever you are during winterthe week recommends Low-key January and decadent holiday eating are all accounted for

-

Nine best TV shows of the year

Nine best TV shows of the yearThe Week Recommends From Adolescence to Amandaland

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred

-

Will Trump's 'madman' strategy pay off?

Will Trump's 'madman' strategy pay off?Today's Big Question Incoming US president likes to seem unpredictable but, this time round, world leaders could be wise to his playbook