Can the Salton Sea be saved?

It's not just about protecting the environment. It's about preventing a public health crisis.

If you don't live near the fading banks of the Salton Sea, it's easy to forget it exists — that is, until the winds pick up.

Depending on which way they are blowing, gusts carry tiny, toxic particulates — and sometimes the stench of decaying fish and sulfur dioxide — from the Colorado Desert to Los Angeles, Phoenix, and points beyond.

The smell is a reminder of the public health crisis that will occur if more isn't done — and quickly — to save the sea.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The Salton Sea is in California's southeastern desert, spanning Riverside and Imperial Counties, and as such has "long been viewed as a local problem out there," Tim Krantz, professor of environmental studies at the University of Redlands, told The Week. "In fact," he said, "it's a regional problem, an interstate problem, an international problem. Mexicali is right there, 1.5 million people are living a short distance from the Salton Sea. It has the potential to be a huge, regional, binational problem."

The sea is actually a shallow lake — the largest in California at 35 miles long and 15 miles wide. (That's 15 times the size of Manhattan.) But the Salton Sea is just 43 feet at its maximum depth. It formed by accident in 1905, when the Colorado River, swollen from heavy rains, broke through a canal and flooded into the dry Salton Sink. It took two years for the breach to be fixed — but by then, nearly 350,000 acres had been filled with water.

Now, the Salton Sea faces a challenge. Formed by circumstance, there is not constant rainfall in the area to sustain the sea, so instead it depends primarily on irrigation runoff from local rivers as well as farms in the Imperial Valley. But as farmers improved their irrigation techniques, the amount of agricultural runoff declined dramatically.

Every year, substantially more water evaporates than enters the sea. Meanwhile, 4 million tons of dissolved salts enter the Salton Sea annually, through agricultural drainage and the Colorado River. With the water evaporating but the salt staying behind, the Salton Sea has nearly double the salinity of the ocean.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

When the Salton Sea was first formed, various fish were stocked for both commercial and sport purposes. But as the sea's salinity began to increase, tens of millions of fish died off, and now it's believed that just algae-eating tilapia and the endangered pupfish remain. It's only a matter of time, scientists warn, before it becomes so salty that even those fish will die.

"As soon as you start reducing inflow into the sea, the salinity concentration will increase exponentially, to the point where it's going to be a dead sea in a matter of a few years," Krantz said. "At this point, even if we build all these wetlands around the edges, it's only going to make it get saltier faster because it's letting less water into the sea."

All the while, in addition to decreased inflow and increased salinity, the Salton Sea has been affected by water politics.

In 2003, the Quantification Settlement Agreement was signed, with the Imperial Irrigation District agreeing to transfer a massive amount of water to the San Diego County Water Authority. Under the agreement, "mitigation water" would still be delivered directly to the Salton Sea through 2017, and a restoration plan would be developed that would address the various challenges, including salinity, fish die-offs, and toxic dust storms.

A plan was delivered in 2007 by the California Natural Resource Agency, but it came with a $9 billion price tag and was effectively shelved by lawmakers.

In 2015, Gov. Jerry Brown (D) tried again, launching the Salton Sea Task Force and directing agencies to put together a 10-year management plan that would construct, in the short-term, 9,000 to 12,000 acres of habitat and dust suppression projects. Overall, Brown called for 18,000 to 25,000 acres of construction.

But Krantz said the idea, while it's a "good plan," is too little, too late. Sea levels are already at the point of reduction, he explained, so the construction is "not going to help."

The Pacific Institute, a nonprofit organization with a focus on freshwater research, estimates that in the next 15 years, the amount of water flowing into the Salton Sea will decrease by 40 percent, its volume will decrease by more than 60 percent, and its salinity will triple. As water disappears, 100 square miles of lakebed — which contains natural toxins plus the pesticides, fertilizers, and waste that come via agricultural runoff — will be exposed. There is so much arsenic and selenium in the lakebed soil, the Riverside Press-Enterprise reports, that it qualifies for disposal in a toxic dump.

Dust storms whip the harmful particulates into the air, wreaking havoc on nearby lungs. "These are super fine sediments," Krantz said. "They are so small if you breathe them in, you cannot expel them from your lungs, and they will infuse directly through your lung tissue into your bloodstream, carrying with them arsenic and selenium and whatever other chemicals are attached."

Moreover, Krantz said the problem will worsen over the next 10 to 15 years as more of the sea bottom is exposed. Already, Imperial County has double California's rate of asthma-related ER visits and hospitalization for children, California public health figures show, and health advisories warning of air pollution are frequent.

In the 1950s and 1960s, the Salton Sea was a playground for celebrities like Frank Sinatra and Dean Martin, who flocked there to go fishing, boating, and waterskiing. There were hotels on the shoreline, and people purchased land by flying over in a helicopter and choosing their parcels from the air.

But as the Salton Sea became saltier and more polluted, the celebrities stopped coming out, and storms in the 1970s flooded homes and businesses around the water. In the aftermath, many restaurants and hotels closed, and houses were abandoned.

Still, the Salton Sea Recreation Area continues to attract visitors, and thousands of people live around the sea in small towns like Salton City and Bombay Beach. Many of them are retirees, who have spent their life savings on a property, but there are also young families — mostly Hispanic — who are drawn to the affordable housing.

Kerry Morrison, director of the nonprofit EcoMedia Compass and founder of Save Our Sea, came to the Salton Sea in 2011 to shoot a music video. He became fascinated by the sea's precarious situation — "amazed at the potential and beauty" of the area, but "appalled at the inaction of the state," he said. "Being from Southern California, it was mind-blowing that this was allowed to happen."

Morrison moved nearby, intent on telling the sea's story. "I saw how much potential the whole region has with some care and love and money from the state and private help," he said. He's now the honorary mayor of West Shores and is organizing the community to advocate on their own behalf.

They face an uphill battle: Property values are plummeting, the air quality is worsening, and a language barrier prevents Spanish-speaking residents from staying informed. About 1 in 4 people in Imperial County live in poverty, so they can't just pack up their bags and leave.

"We have to keep the community running," Morrison said. "We're writing letters and staying constructive. My mother passed away when I was young from lung disease, and I've realized a lot of the wonderful people I've met out here could see a similar fate if they're not helped. I don't want to see anyone else go through that."

The campaign to save the Salton Sea is woefully underfunded. It's going to take "embracing science and technology" and fully realizing the stakes to solve the crisis, Morrison said. "People need to understand this issue goes far beyond the shoreline," he added. "They need to understand a lot of families live here, and millions and millions of animals will die if they don't get help."

There are a few options for how to save the Salton Sea, though Krantz emphasizes that they all must result in more water being brought to the lakebed. The "only solution," he says, "would be to either bring in more water from the Colorado River — but that's not guaranteed either in a drought — or bring in water from the Gulf of California, south of Mexicali, or from the Pacific coast."

Large tunnels would have to be built through the mountains to get water in from the Pacific, making the Gulf of California option the least expensive. As long as the water could be elevated at least 40 feet, Kranz explained, physics would do the rest: "It's all gravity into the Salton basin," he said. But increased inflow would just go toward "keeping the lake full, albeit salty, so it doesn't blow dust," he added. "We'd still have a dead sea in the middle."

Another idea that has been floated is to create a ring around the edge of the sea, stopping some sand particles from blowing over the lakebed because they would first fall into the moat. The challenge here is that the "Salton Sea is immediately astride the San Andreas fault," Krantz said. "One significant earthquake and this water infrastructure goes right into the mud."

Morrison, for his part, wants to see water imported, because "if we have enough water, we have something to work with," he said. "It's not enough just pushing around dust."

In January, V. Manuel Perez, the fourth district supervisor of Riverside County, proposed the latest plan to save the Salton Sea: a $400 million project that would build a protective barrier around the water, preserving the shoreline. It would also restore and expand the Whitewater River where it flows into the Salton Sea. The proposal still needs the approval of the Riverside County Board of Supervisors.

Otherwise, the Pacific Institute's Hazard's Toll report estimates that inaction will cost $29 billion to $70 billion over the next 30 years. Krantz says he "hates to be a doomsayer," but at this point to get people to realize the severity of the situation, "it's going to take some serious dust and air quality events where literally dozens, perhaps hundreds of people, are going to be hospitalized and people's lives are going to be lost."

What's often overlooked in discussing the Salton Sea is the beauty that remains. Standing outside the North Shore Beach and Yacht Club, where the Beach Boys and Jerry Lewis once docked their boats, the Salton Sea is bordered by the towering Santa Rosa Mountains. As the sun dips behind the peaks, the glassy water picks up the colors of the sunset — pink, blue, purple, or yellow, depending on the sky that day. The only noise comes from the birds swooping and squawking as they fly to and from the shore, plus the sand — crushed up barnacles and fish bones — crunching underfoot.

If the Salton Sea disappears, so do the herons, egrets, and pelicans that winter there. And that's only the beginning of what would be lost. Because of the magnitude of the crisis — a perfect storm of water politics, climate change, drought, and funding issues — it can be hard to fully grasp just what's happening, let alone try to come up with a solution.

But for a state that prides itself on being a global leader in fighting climate change and enacting environmental protections, that's no excuse.

Catherine Garcia has worked as a senior writer at The Week since 2014. Her writing and reporting have appeared in Entertainment Weekly, The New York Times, Wirecutter, NBC News and "The Book of Jezebel," among others. She's a graduate of the University of Redlands and the Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism.

-

Prince Harry’s court battle with ‘highly intrusive’ press

Prince Harry’s court battle with ‘highly intrusive’ pressIn the Spotlight As the Duke of Sussex and other high-profile claimants begin their trial against Associated Newspapers, ‘the stakes for all sides are high’

-

Wellness retreats to reset your gut health

Wellness retreats to reset your gut healthThe Week Recommends These swanky spots claim to help reset your gut microbiome through specially tailored nutrition plans and treatments

-

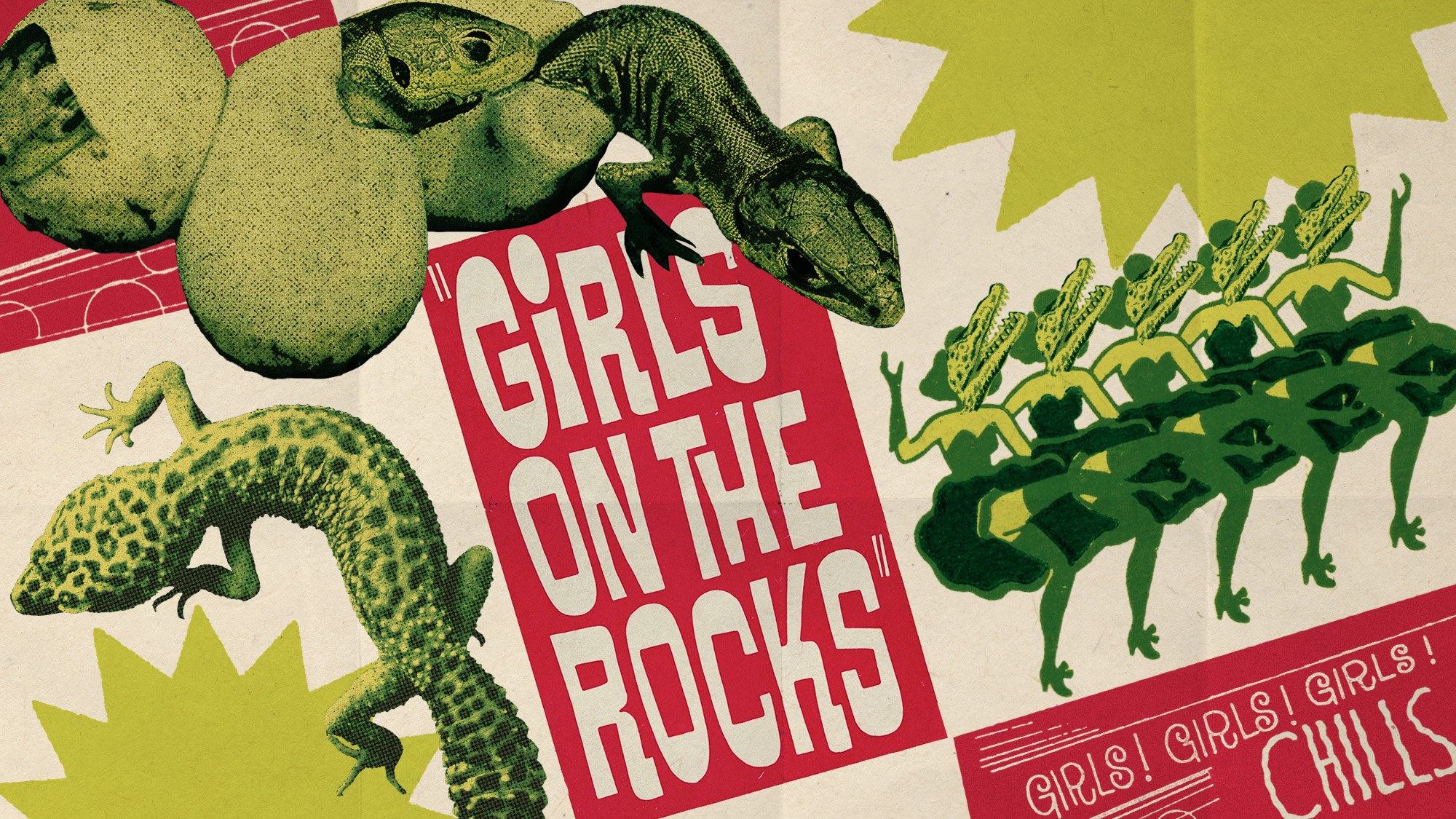

Climate change could lead to a reptile ‘sexpocalypse’

Climate change could lead to a reptile ‘sexpocalypse’Under the radar The gender gap has hit the animal kingdom