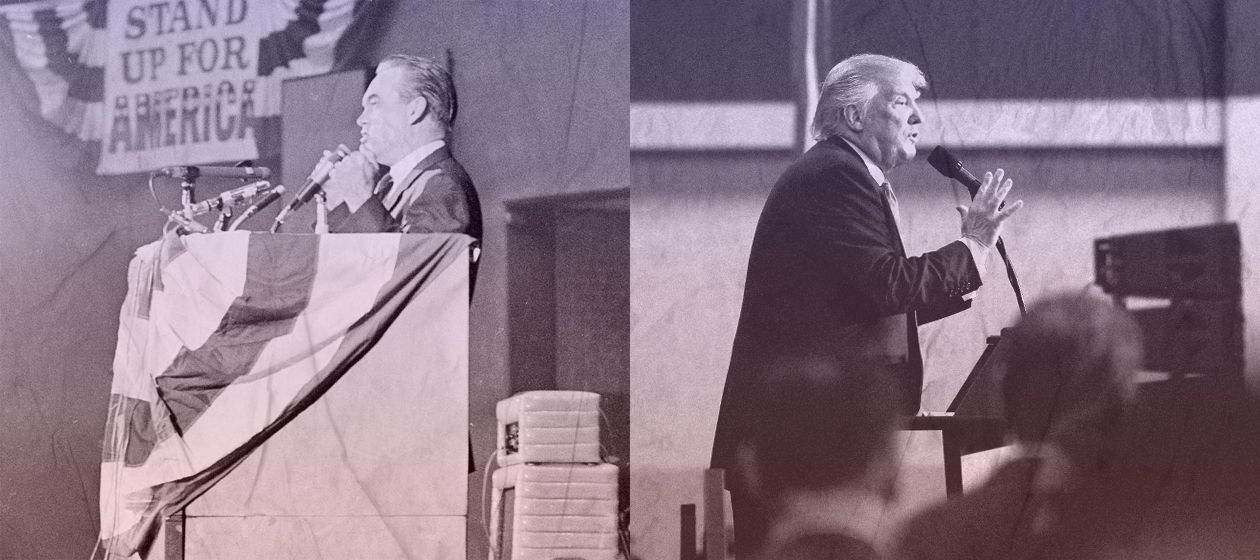

Trump's tribalist revival

The president's "America, love it or leave it" attitude is hardly new. In fact, it's one of the deepest — and darkest — facets of our nation's history.

If politics is about policymaking, then Donald Trump's presidency thus far has been an exercise in weakness and ineptitude.

But if politics is about something deeper than policy — about moving and shaping public opinion, and thus shifting the political landscape at a more fundamental level — then the distressing truth is that President Trump has been remarkably effective in his nearly three years at the center of American public life. Since he declared his candidacy for president in June 2015, Trump has managed, above all, to revive and empower a tradition of tribalistic American patriotism that had grown largely dormant over the past half century.

The president warns ominously that immigrant children ("alien minors") are "not innocent"; the NFL responds to the president's racialized taunts by warning football teams that they will be fined for their players' refusal to stand for the national anthem; Trump suggests that players who persist in their protest of police brutality by kneeling during the anthem "shouldn't be in the country" — in these examples from just the past two days, we can see Trump and his rhetoric tapping into and unleashing something old, potent, and poisonous in American life. The president's critics are wrong to describe these sentiments as "un-American." On the contrary, they are profoundly American, drawing on some of the deepest and darkest currents in our history.

Subscribe to The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The last time such sentiments were so prominent in our public life was the era of the civil rights movement and Vietnam War. Whereas the left practiced an aspirational form of patriotism (that sometimes lapsed into outright anti-Americanism), others responded defensively by saying, in effect, "this country is our home, and it's good just the way it is." In its nastiest form, it could flirt with and even embrace an ethic of expulsion, banishment, and exile for those who persisted in their criticisms of the country. "America, love it or leave it!": the phrase echoed through George Wallace's remarkably potent third-party campaign for president in 1968, and in somewhat subtler form in Richard Nixon's subsequent efforts to absorb the Wallace voters into the Republican Party while moderating and sublimating their anger and resentment.

By the time of Ronald Reagan's election to the presidency, the process of co-optation and sublimation was complete. Democrats are instinctive idealists, because members of the party's electoral coalition (blacks and other ethnic minorities, liberal women, more recently gays and lesbians) can't help but look toward the future, to a time when the country's highest ideals will be more fully realized and past injustices slowly and painstakingly overcome. But the Republican Party under Reagan affirmed its own version of patriotic idealism. Rather than telling the left to get out of the country if they didn't love it as it is, Reagan described an America perpetually shining as a light of liberty in the world, opening a space for individuals, families, and businesses to thrive at home while also serving as a beacon for hope to oppressed people everywhere.

Americans didn't need to choose between loving and leaving the country. Instead, Reagan talked about a country that was infinitely worthy of love and invited all Americans to embrace it.

Many took him up on the offer. In this respect, Reagan recaptured and transformed the idealism that fueled the first two decades of the Cold War, especially in the distinctly high-minded form it took during the short-lived Kennedy administration.

But just as the nobility of Camelot degraded within a few years into a national feud more rancorous than any since the Civil War, so Reagan's revival of patriotic purpose eventually petered out (after an impressive run of roughly three decades). Then, in the wake of interminable wars and a crippling financial crisis, it curdled into polarized factionalism.

Into that factionalism plunged Donald Trump, reverting to the language of tribalism, talking in angry terms about the country as an armed camp in need of walls to protect it from dangerous outsiders and conducting domestic politics as an ongoing exercise in dividing the country into antagonistic groups of friends and enemies. Like Wallace reborn for the 21st century and given all the amplification of the Oval Office and a Twitter account, Trump rails against anyone who would dare suggest that the country needs to aspire to be anything more than it already is — or once was, before its pre-existing greatness was tarnished by them.

Despite what many on the center-right and center-left allowed themselves to believe over the past few decades, American tribalism never died. It remained there, politically dormant, under the surface, lacking a champion, existing in a state of untapped potential — a potential that Trump has now activated and explicitly encourages every day.

There's no telling how many Americans will end up finding this mode of "love it or leave it" patriotism appealing — or how ugly American politics will become, after two and a half (or six and a half) more years of presidential encouragement.

Sign up for Today's Best Articles in your inbox

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Damon Linker is a senior correspondent at TheWeek.com. He is also a former contributing editor at The New Republic and the author of The Theocons and The Religious Test.

-

Why Rikers Island will no longer be under New York City's control

Why Rikers Island will no longer be under New York City's controlThe Explainer A 'remediation manager' has been appointed to run the infamous jail

-

California may pull health care from eligible undocumented migrants

California may pull health care from eligible undocumented migrantsIN THE SPOTLIGHT After pushing for universal health care for all Californians regardless of immigration status, Gov. Gavin Newsom's latest budget proposal backs away from a key campaign promise

-

Is Apple breaking up with Google?

Is Apple breaking up with Google?Today's Big Question Google is the default search engine in the Safari browser. The emergence of artificial intelligence could change that.

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred

-

Will Trump's 'madman' strategy pay off?

Will Trump's 'madman' strategy pay off?Today's Big Question Incoming US president likes to seem unpredictable but, this time round, world leaders could be wise to his playbook

-

Democrats vs. Republicans: who are the billionaires backing?

Democrats vs. Republicans: who are the billionaires backing?The Explainer Younger tech titans join 'boys' club throwing money and support' behind President Trump, while older plutocrats quietly rebuke new administration

-

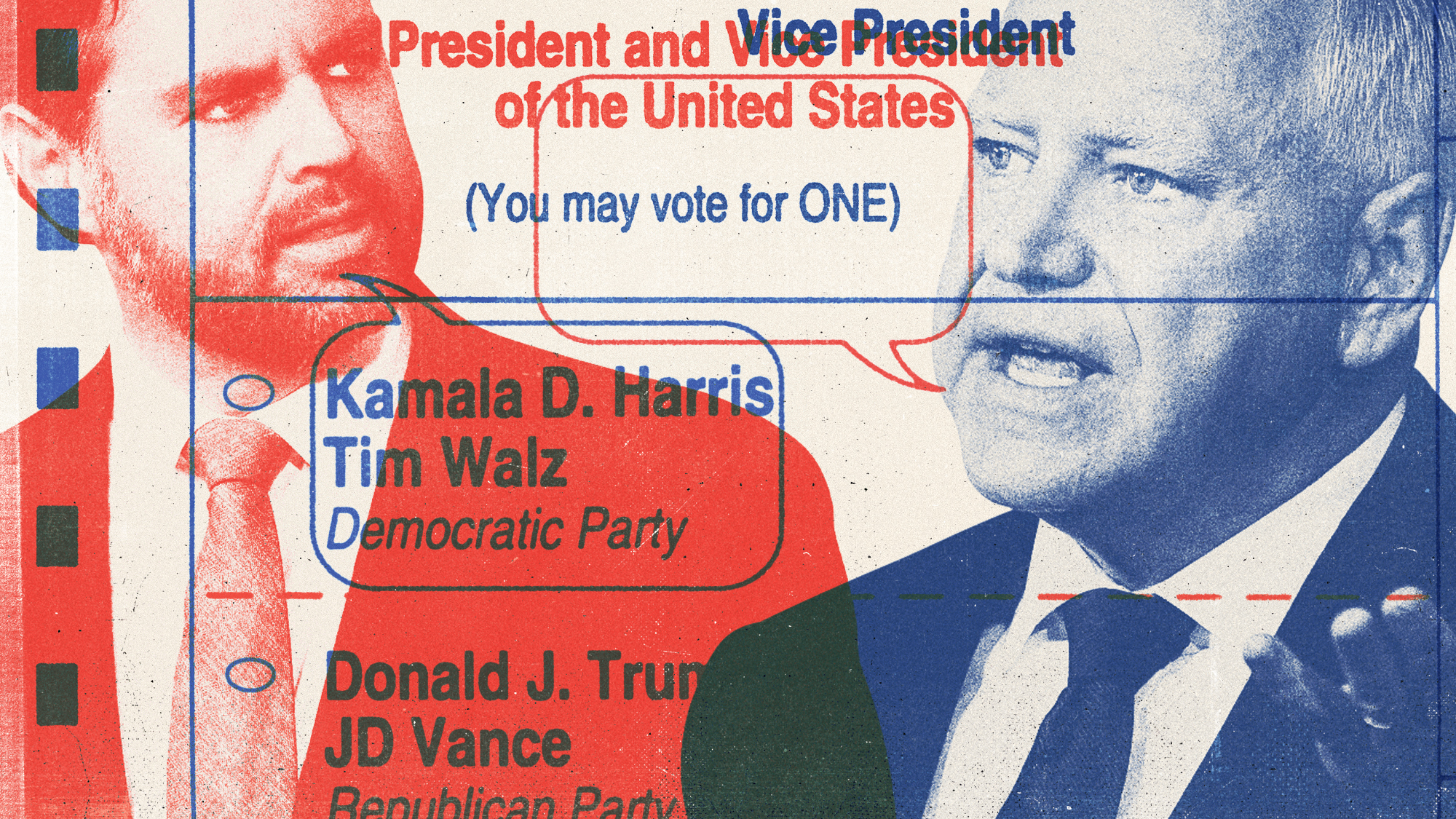

US election: where things stand with one week to go

US election: where things stand with one week to goThe Explainer Harris' lead in the polls has been narrowing in Trump's favour, but her campaign remains 'cautiously optimistic'

-

Is Trump okay?

Is Trump okay?Today's Big Question Former president's mental fitness and alleged cognitive decline firmly back in the spotlight after 'bizarre' town hall event

-

The life and times of Kamala Harris

The life and times of Kamala HarrisThe Explainer The vice-president is narrowly leading the race to become the next US president. How did she get to where she is now?

-

Will 'weirdly civil' VP debate move dial in US election?

Will 'weirdly civil' VP debate move dial in US election?Today's Big Question 'Diametrically opposed' candidates showed 'a lot of commonality' on some issues, but offered competing visions for America's future and democracy