Scientists just created a light that is 1 billion times as bright as the sun

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

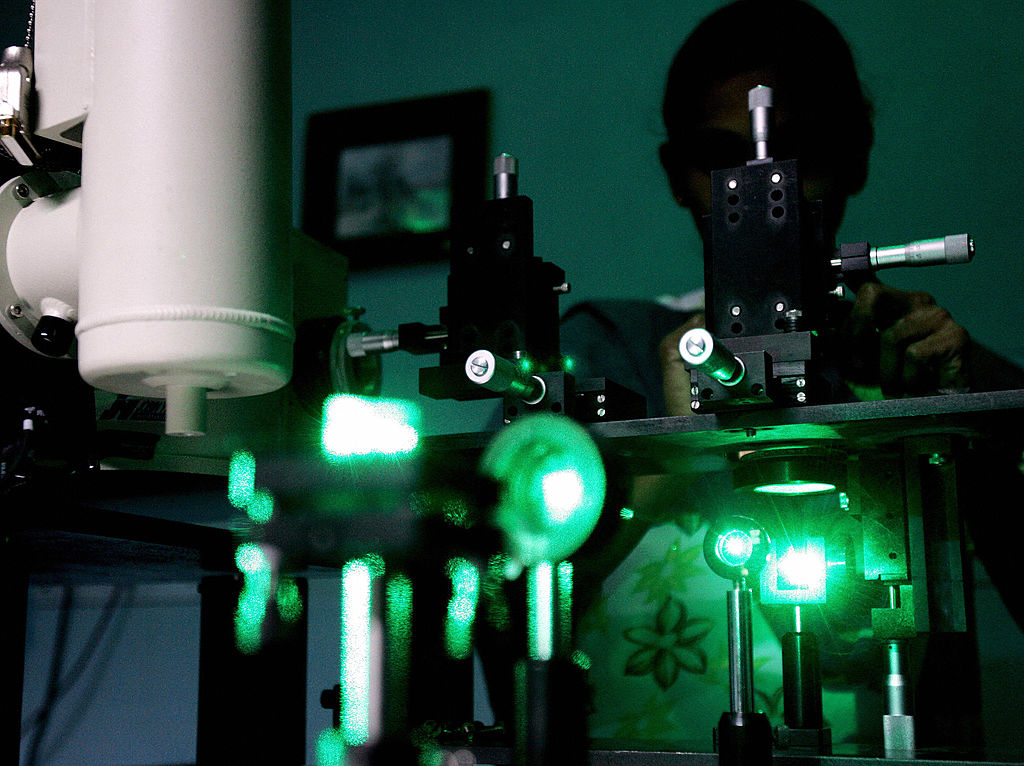

A million suns isn't cool. You know what's cool? A billion suns. Physicists from the University of Nebraska's aptly-named Extreme Light Laboratory have just made the brightest light ever produced on Earth, and it is one billion times brighter than the surface of the sun, Phys.org reports.

The super bright laser beam is helping researchers understand how light and matter interact. When light from a regular bulb or the sun strikes a surface, it "scatters," which is what allows us to see. In everyday circumstances, an electron scatters just a couple photons of light at a time, but with the University of Nebraska's laser, almost 1,000 photons scatter at once.

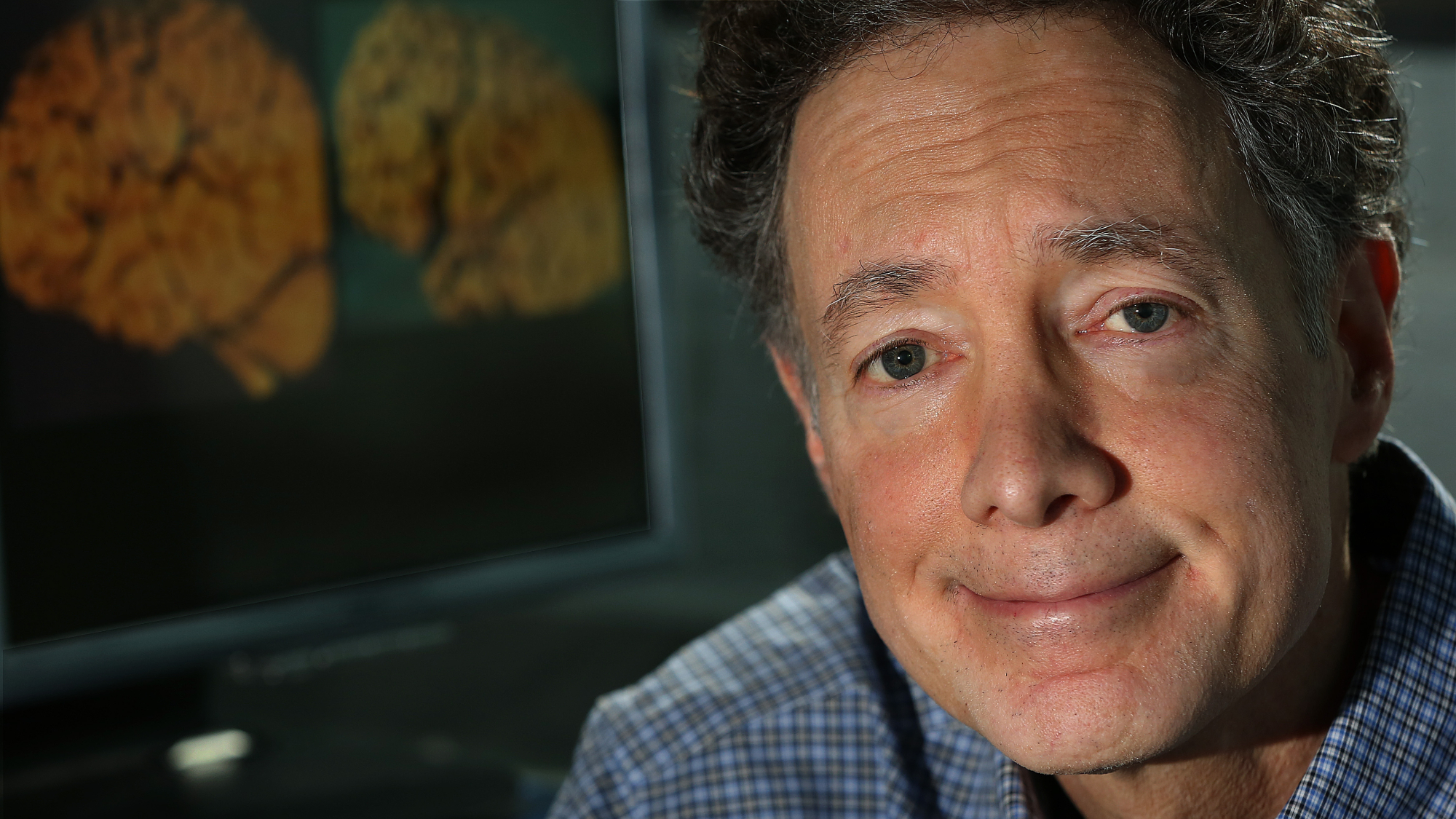

"It's as if things appear differently as you turn up the brightness of the light, which is not something you normally would experience," said the University of Nebraska's Donald Umstadter. "[An object] normally becomes brighter, but otherwise, it looks just like it did with a lower light level. But here, the light is changing [the object's] appearance. The light's coming off at different angles, with different colors, depending on how bright it is."

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

In one example, the scientists were able to create a high-resolution X-ray of a USB drive, photographing interior details that aren't able to be seen with regular X-rays. Understanding the phenomenon could help scientists find more sophisticated ways to "hunt for tumors or microfractures that elude conventional X-rays, map the molecular landscapes of nanoscopic materials now finding their way into semiconductor technology, or detect increasingly sophisticated threats at security checkpoints," Phys.org writes. "Atomic and molecular physicists could also employ the X-ray as a form of ultrafast camera to capture snapshots of electron motion or chemical reactions."

Read more about the Extreme Light Laboratory and its findings at Phys.org.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Jeva Lange was the executive editor at TheWeek.com. She formerly served as The Week's deputy editor and culture critic. She is also a contributor to Screen Slate, and her writing has appeared in The New York Daily News, The Awl, Vice, and Gothamist, among other publications. Jeva lives in New York City. Follow her on Twitter.

-

Local elections 2026: where are they and who is expected to win?

Local elections 2026: where are they and who is expected to win?The Explainer Labour is braced for heavy losses and U-turn on postponing some council elections hasn’t helped the party’s prospects

-

6 of the world’s most accessible destinations

6 of the world’s most accessible destinationsThe Week Recommends Experience all of Berlin, Singapore and Sydney

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

Blue Origin launches Mars probes in NASA debut

Blue Origin launches Mars probes in NASA debutSpeed Read The New Glenn rocket is carrying small twin spacecraft toward Mars as part of NASA’s Escapade mission

-

Dinosaurs were thriving before asteroid, study finds

Dinosaurs were thriving before asteroid, study findsSpeed Read The dinosaurs would not have gone extinct if not for the asteroid

-

SpaceX breaks Starship losing streak in 10th test

SpaceX breaks Starship losing streak in 10th testspeed read The Starship rocket's test flight was largely successful, deploying eight dummy satellites during its hour in space

-

Rabbits with 'horns' sighted across Colorado

Rabbits with 'horns' sighted across Coloradospeed read These creatures are infected with the 'mostly harmless' Shope papilloma virus

-

Lithium shows promise in Alzheimer's study

Lithium shows promise in Alzheimer's studySpeed Read Potential new treatments could use small amounts of the common metal

-

Scientists discover cause of massive sea star die-off

Scientists discover cause of massive sea star die-offSpeed Read A bacteria related to cholera has been found responsible for the deaths of more than 5 billion sea stars

-

'Thriving' ecosystem found 30,000 feet undersea

'Thriving' ecosystem found 30,000 feet underseaSpeed Read Researchers discovered communities of creatures living in frigid, pitch-black waters under high pressure

-

New York plans first nuclear plant in 36 years

New York plans first nuclear plant in 36 yearsSpeed Read The plant, to be constructed somewhere in upstate New York, will produce enough energy to power a million homes