How coronavirus eventually gripped India - and why it took so long

It now has more cases than anywhere in the world except Brazil and the US

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

As Covid-19 spread through Europe in February and March, India braced for a similar wave of infections.

Worried politicians placed the billion-strong population under a strict lockdown and sent healthcare workers out into villages to look for coronavirus symptoms - yet at first, medics found little to report.

“South Asia’s relatively low case numbers are a bit of a puzzle, especially given high population density and poor health care systems across the region”, Foreign Policy reported in April.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Now, however, India’s coronavirus count is “rising at an alarming rate”, says the BBC.

The authorities today reported 23,000 new cases, pushing India ahead of Russia to become the country with the third-highest number of confirmed infections, behind only the US and Brazil. According to latest figures, India has recorded a total of more than 700,000 cases and nearly 20,000 Covid-related deaths.

What’s happening?

Infection rates across India have been climbing as a strict lockdown in place since late March is gradually lifted, with most activities now allowed “after the economy nose-dived during the shutdown”, The Guardian reports.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Even though masks remain compulsory and commuter trains are suspended, many Indians are complacent about Covid-19, says Jayaprakash Muliyil, an epidemiologist at the Christian Medical College in Vellore, Tamil Nadu.

“The general population’s anxiety about the disease is low,” he told the journal Nature.

A sharp increase in Covid-related fatalities may soon change that. Indian officials “recorded 421 new deaths from the virus” on Sunday, “taking the toll to over 2,300 in the five days of this month alone”, The Times of India reports.

And the official numbers almost certainly don’t tell the whole story.

A nationwide testing programme found that 0.73% of the population had Covid-19 antibodies in their blood by early June. That would imply that ten million Indians had already “contracted the deadly contagion”, The Hindustan Times reports.

The official death toll, too, is likely to be well below the true figure. “At least half of all deaths will happen in rural villages - around 66% of our population,” says diseases expert Muliyil. “And there are no real mechanisms to ascertain causes of deaths in these villages.”

Why did coronavirus seem to spread slowly at first?

At least part of the explanation probably lies in the size of India’s population and the relatively small proportion of the country’s people who had been tested. By the end of April, India had conducted 830,201 tests, or 614 for every million people - among the lowest testing rates in the world.

Other potential explanations have also been advanced. “After coronavirus entered India, speculations were rife that it won’t be able to survive the scorching heat or humid weather conditions,” says India.com. Even a “unique Indian genome” was credited with protecting the country - but those theories have now “fallen flat”, adds the news site.

While scientists do believe that the coronavirus spreads less rapidly in hot weather, high temperatures alone do not offer complete protection.

Some researchers also believe that the BCG vaccine, widely used in India to prevent tuberculosis, may offer some protection against Covid-19 - but only to the extent of slowing, rather than stopping, its spread.

What next?

Epidemiologists now expect the outbreak to accelerate, especially in India’s crowded cities.

The Guardian reports that “state government officials fear Delhi, home to 25 million people, could record more than half-a-million cases by the end of the month”, with disastrous consequences for public health.

In Delhi and Mumbai, hospitals are already “struggling to accommodate critically ill patients”, says Nature.

Some restrictions are likely to be reimposed and others that would have been lifted will be retained. “The Taj Mahal, which was scheduled to reopen on Monday, will remain closed,” reports Al Jazeera.

But a repeat of the India-wide shutdown is unlikely.

“The lockdown all over the country was not the right response,” Muliyil told Nature. “It brought misery to untold numbers of people and destroyed lives. And we haven’t been able to repair its consequences for society.”

Holden Frith is The Week’s digital director. He also makes regular appearances on “The Week Unwrapped”, speaking about subjects as diverse as vaccine development and bionic bomb-sniffing locusts. He joined The Week in 2013, spending five years editing the magazine’s website. Before that, he was deputy digital editor at The Sunday Times. He has also been TheTimes.co.uk’s technology editor and the launch editor of Wired magazine’s UK website. Holden has worked in journalism for nearly two decades, having started his professional career while completing an English literature degree at Cambridge University. He followed that with a master’s degree in journalism from Northwestern University in Chicago. A keen photographer, he also writes travel features whenever he gets the chance.

-

Why is the Trump administration talking about ‘Western civilization’?

Why is the Trump administration talking about ‘Western civilization’?Talking Points Rubio says Europe, US bonded by religion and ancestry

-

Quentin Deranque: a student’s death energizes the French far right

Quentin Deranque: a student’s death energizes the French far rightIN THE SPOTLIGHT Reactions to the violent killing of an ultraconservative activist offer a glimpse at the culture wars roiling France ahead of next year’s elections

-

Secured vs. unsecured loans: how do they differ and which is better?

Secured vs. unsecured loans: how do they differ and which is better?the explainer They are distinguished by the level of risk and the inclusion of collateral

-

A Nipah virus outbreak in India has brought back Covid-era surveillance

A Nipah virus outbreak in India has brought back Covid-era surveillanceUnder the radar The disease can spread through animals and humans

-

How music can help recovery from surgery

How music can help recovery from surgeryUnder The Radar A ‘few gentle notes’ can make a difference to the body during medical procedures

-

Covid-19 mRNA vaccines could help fight cancer

Covid-19 mRNA vaccines could help fight cancerUnder the radar They boost the immune system

-

The new Stratus Covid strain – and why it’s on the rise

The new Stratus Covid strain – and why it’s on the riseThe Explainer ‘No evidence’ new variant is more dangerous or that vaccines won’t work against it, say UK health experts

-

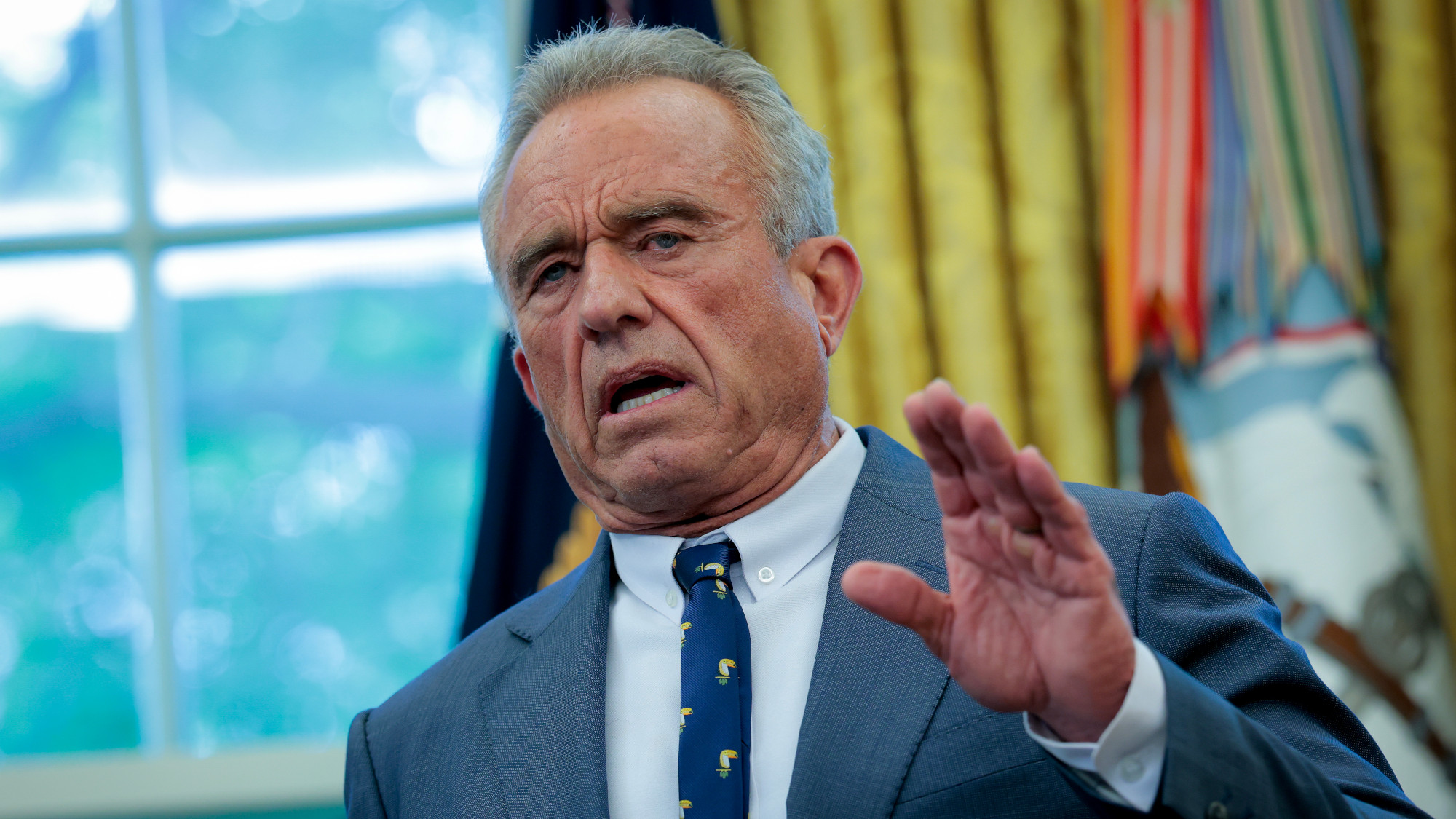

RFK Jr. vaccine panel advises restricting MMRV shot

RFK Jr. vaccine panel advises restricting MMRV shotSpeed Read The committee voted to restrict access to a childhood vaccine against chickenpox

-

RFK Jr. scraps Covid shots for pregnant women, kids

RFK Jr. scraps Covid shots for pregnant women, kidsSpeed Read The Health Secretary announced a policy change without informing CDC officials

-

New FDA chiefs limit Covid-19 shots to elderly, sick

New FDA chiefs limit Covid-19 shots to elderly, sickspeed read The FDA set stricter approval standards for booster shots

-

RFK Jr.: A new plan for sabotaging vaccines

RFK Jr.: A new plan for sabotaging vaccinesFeature The Health Secretary announced changes to vaccine testing and asks Americans to 'do your own research'