Oxford scientists: ‘here’s what we are doing to develop our coronavirus vaccine’

Researchers working to develop the world’s first Covid-19 vaccine explain how it is being done

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Rebecca Ashfield, senior project manager at the University of Oxford, and Pedro Folegatti, clinical research fellow at the University of Oxford, on the effort to develop the first Covid-19 vaccine.

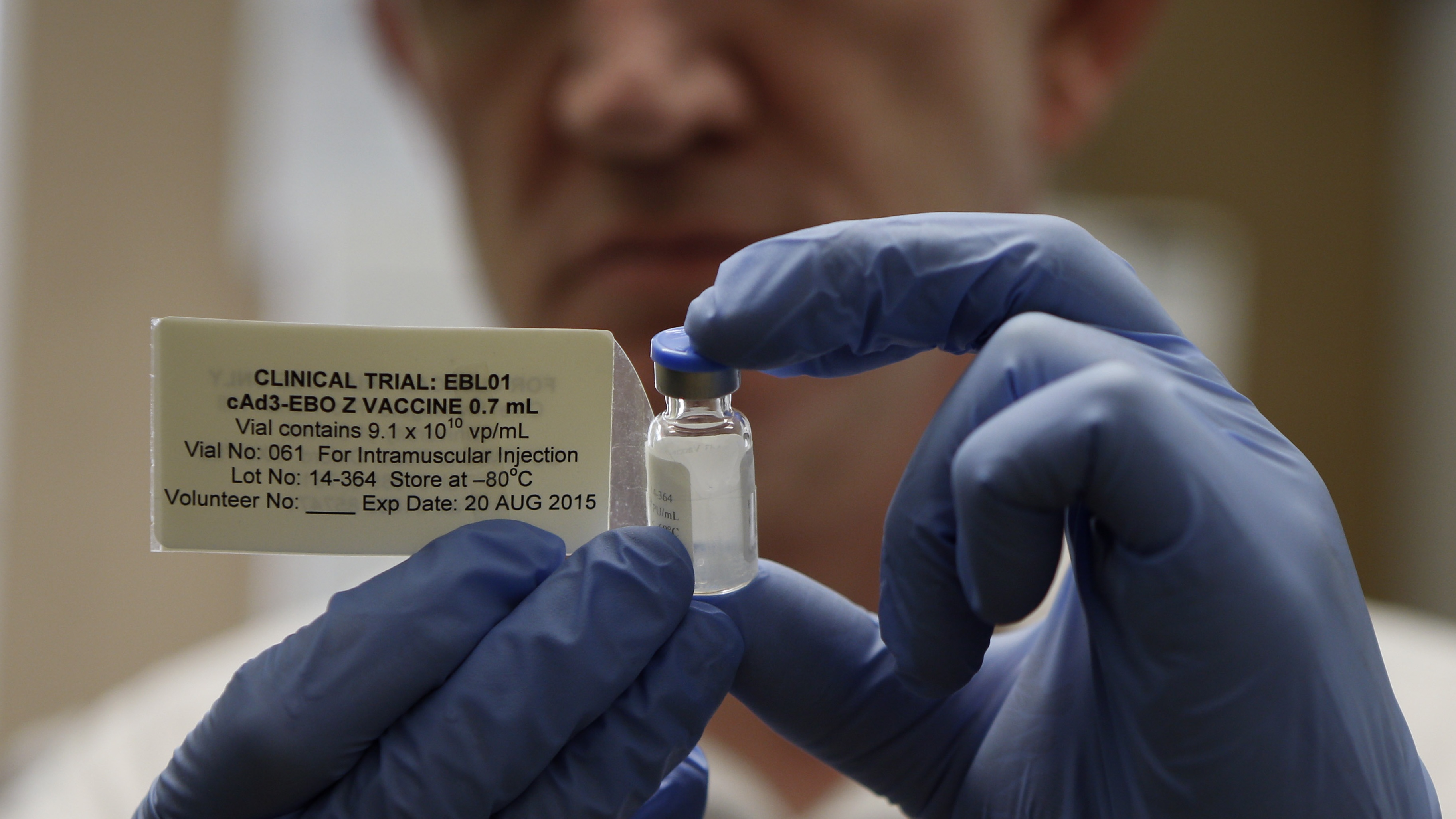

Of the hundreds of potential Covid-19 vaccines in development, six are in the final stages of testing, known as phase three clinical trials. One of these - ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 - is the vaccine we’re developing at the University of Oxford.

To be approved, vaccines need to go through multiple rounds of testing to show that they’re safe and effective. A combined phase one and phase two trial of the Oxford vaccine has demonstrated that it is safe – with only short-term side-effects and no serious unexpected events reported – and that it elicits an immune response.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The purpose of a phase three trial is to assess whether this vaccine-induced immune response is strong enough to actually protect people from Covid-19. Proving this would pave the way for the vaccine to become publicly available.

How a phase three trial works

Usually a phase three trial has two groups, one receiving the vaccine being tested and the other a placebo or “control” injection, for example saline or a vaccine against a different disease.

To show that the vaccine is effective, there should be significantly fewer cases of the target disease in the vaccinated group compared with the control group. Depending on infection rates for the disease, a phase three vaccine trial may involve thousands to tens of thousands of volunteers.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

For ChAdOx1 nCoV-19, clinical trial volunteers are located in countries across five continents: the UK, Brazil, South Africa, the US and India. The vaccine is being evaluated in these different regions and populations of the world to ensure that results of the trial are “generalisable” – that is, that its findings can be said to apply to people outside of the groups tested.

In the UK we’re testing the vaccine in health workers, as they’re more likely to be exposed to infection than the general population. The trial there also includes volunteers from the public who are over 70. Older people are at higher risk of developing severe disease, so it’s important to know if they respond to the vaccine.

Oxford and our international partners have already vaccinated approximately 17,000 people in the first three countries selected (the UK, Brazil and South Africa), with half receiving a control vaccine.

Most volunteers are receiving a booster vaccination one to three months after the first, as data from our phase one and phase two trial indicates that this strengthens the immune response – although it’s not yet clear whether two doses will be necessary to protect against Covid-19.

Once vaccinated, volunteers go about their daily lives, but are monitored to see if they get the disease.

Importantly, they are told to take the same precautions against infection as everyone else – this is because we don’t yet know if the vaccine works, and also because half of the volunteers will have received a control (non-Covid) vaccine.

Running phase three clinical trials in several different countries in record time is a huge logistical challenge. Working with experienced international teams has made the complex process of shipping equipment and vaccines manageable, but it’s been especially taxing due to travel and flight restrictions in the UK and elsewhere.

There are also lots of different operations that need to be coordinated. We’re testing the vaccine with our partners at three trial sites in Brazil and seven in South Africa, for example.

Will the vaccine be safe?

Most vaccines take at least five years to go through clinical trials, and there have been questions around whether Covid-19 vaccines are being “rushed through”.

The Oxford vaccine has completed a programme of pre-clinical safety testing in animals and is going through the same carefully regulated process as vaccines against other diseases. It will be tested in more volunteers in the planned clinical trials than many drugs or vaccines that are already licensed.

Vaccines like Oxford’s are being developed rapidly because of the coordinated efforts of large international teams of scientists and doctors. Safety, ethics and regulatory committees are speeding things up by prioritising approval processes ahead of those for other vaccines and medicines.

Nevertheless, the same rigorous standards are applied to candidate Covid-19 vaccines, ensuring no corners are cut in terms of vaccine safety.

When will we know if the Oxford vaccine works?

There’s a good chance we’ll know whether the ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 vaccine is effective before the end of 2020. After the successful completion of phase three trials, regulatory bodies in each country will need to review the available data before approving the vaccine for general use.

AstraZeneca, the firm partnering Oxford to develop the vaccine, is overseeing a scaling up of manufacturing in parallel with clinical testing so that hundreds of millions of doses can be available if the vaccine is shown to be safe and effective.

Rebecca Ashfield, senior project manager at the University of Oxford, and Pedro Folegatti, clinical research fellow at the University of Oxford

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.