Would handing No. 10’s powers to local leaders have improved the UK’s Covid response?

Countries taking a more regional approach have had success in tackling virus - and avoided domestic disputes

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Prior to the coronavirus pandemic, England’s regional mayors rarely made headlines outside of their local newspapers.

But as The Guardian’s Simon Jenkins writes, “suddenly mayors matter”, as northern leaders clash with Downing Street over local lockdown measures and financial support for struggling businesses.

While many other countries have handed more power to regional officials, Boris Johnson’s government has been “doing its best to ignore local expertise on Covid”, says Jenkins.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

But could stripping No. 10 of some of its decision-making powers have boosted the UK’s ability to respond quickly after the virus hit British shores?

Power to the people

As British Foreign Policy Group director Sophia Gaston tweets, “many of the nations that have performed ‘best’ in the pandemic have strong regional governance frameworks”, while the UK is very much “in the infancy of its devolution story”.

Devolution in England kicked up a notch under George Osborne, who in 2015 invited big cities to join Manchester in bidding for more devolved powers, on the precondition that they agreed to be governed by a directly elected mayor.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

The then-chancellor also announced plans to deliver Greater Manchester’s first mayor through the Cities Devolution Bill, which granted the local authority influence over transport, housing, planning, policing and public health.

But further devolution efforts stalled when Osborne returned to the backbenches in 2016 following Theresa May’s appointment as prime minister. And as Gaston notes, “efforts to pivot mid-crisis from a national to regional approach [to the pandemic] highlight how far we have to go”.

The New Statesman’s political editor Stephen Bush says that “British devolution isn’t built for a crisis like Covid-19”. Pointing to the different measures being imposed across the four nations of the UK, Bush writes that “it’s hard to see how… devolved governments can successfully pursue lockdown strategies when they don’t control the necessary financial levers to make them survivable or bearable”.

In the UK, these levers are still controlled by Westminster, prompting rows such as that between Greater Manchester Mayor Andy Burnham and No. 10 this week over a cash injection to offset the financial impact of tougher coronavirus restrictions in the region.

The problem facing the UK in its pandemic response is that devolution is currently “not designed for a novel pandemic such as Covid-19”, where “your ability to fund financial support packages during lockdown is inextricably linked to your ability to deliver lockdown restrictions” dictated by Downing Street, Bush says.

Given this lack of control over funding to support their cities, some regional mayors have concluded that Tier 2 measures - in which Covid-safe businesses remain open - are unsustainable. Instead, mayors including Liverpool’s Steve Rotheram have asked for Tier 3 measures with the maximum financial support for shuttered businesses.

Federal gains

The general consensus among experts is that Germany stands head and shoulders above other European nations in its Covid planning. Latest figures show that the country has reported 397,922 coronavirus cases, but just 9,911 related deaths.

“Germany has gone from cursing its lead-footed, decentralised political system to wondering if federalism’s tortoise versus hare logic puts it in a better position to brave the pandemic”, The Guardian’s Berlin bureau chief Philip Oltermann wrote in April, as governments worldwide struggled to tackle the growing health crisis.

German federalism gives its 16 states - lander in German - power over policy areas such as health, education and cultural affairs. And while this approach can make it difficult to move the country as one, it may also explain why Germany has achieved comparatively high Covid testing rates.

Public health is not dominated “by one central authority but by approximately 400 public health offices, run by municipality and rural district administrations”, Oltermann explains. This allowed for the quick launch of hundreds of autonomous testing labs, many of which existed before health insurers were offering tests.

That said, the federal system is not perfect. As Deutsche Welle reports, efforts to introduce face masks in German secondary schools were hampered by “Germany's two most populous and influential states… moving in opposite directions” on the issue.

But nowhere has the federal system been put under more strain than in the US, where “two nations are responding to one virus”, says Ashish Jha on Foreign Affairs. States that “embrace science and the advice of health experts” are containing outbreaks, “while infection rates have spiralled out of control in those that do not”.

Jha suggests that the pandemic has shown up “the weaknesses of the US federal system in the midst of the deadliest disease outbreak in a century”.

Centre cannot hold

While America’s response to the pandemic does little to support the argument that localised governments were better equipped to deal with the pandemic, China’s slow early response does little to bolster the defence of central power.

As Jessie Lau wrote in the New Statesman in late-January, China’s system of concentrating power at the top meant “local officials [were] not incentivised to take decisive action” in the early weeks of the pandemic. The first case in Wuhan, the epicentre of the outbreak, was identified on 8 December, but officials waited more than a month to introduce screening measures.

Dr Jie Yu, a senior research at think tank Chatham House, argues that centralisation “hobbled” China’s immediate response, which “sheds light on the way the Chinese bureaucracy approaches crises”.

“For decades, local governments have made things happen in China,” Yu wrote in February. “But with tighter regulation of lower-level bureaucrats, civil servants across the system now seem less ready, and able, to provide their input, making ineffective and even mistaken policy more likely.”

While clearly less centralised than the Communist Party of China’s governance, a similar criticism is now being levelled at Downing Street.

“Centralised policy-making, diktats from the centre, and refusals over recent months by the Johnson government to devolve authority to local leaders” has fuelled anger across the country, says The Guardian. That anger would probably be less fierce had the government response given more cause for confidence.

Joe Evans is the world news editor at TheWeek.co.uk. He joined the team in 2019 and held roles including deputy news editor and acting news editor before moving into his current position in early 2021. He is a regular panellist on The Week Unwrapped podcast, discussing politics and foreign affairs.

Before joining The Week, he worked as a freelance journalist covering the UK and Ireland for German newspapers and magazines. A series of features on Brexit and the Irish border got him nominated for the Hostwriter Prize in 2019. Prior to settling down in London, he lived and worked in Cambodia, where he ran communications for a non-governmental organisation and worked as a journalist covering Southeast Asia. He has a master’s degree in journalism from City, University of London, and before that studied English Literature at the University of Manchester.

-

The ‘ravenous’ demand for Cornish minerals

The ‘ravenous’ demand for Cornish mineralsUnder the Radar Growing need for critical minerals to power tech has intensified ‘appetite’ for lithium, which could be a ‘huge boon’ for local economy

-

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?IN THE SPOTLIGHT As the president muses about polling place deployments and a centralized electoral system aimed at one-party control, lawmakers are taking this administration at its word

-

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

How corrupt is the UK?

How corrupt is the UK?The Explainer Decline in standards ‘risks becoming a defining feature of our political culture’ as Britain falls to lowest ever score on global index

-

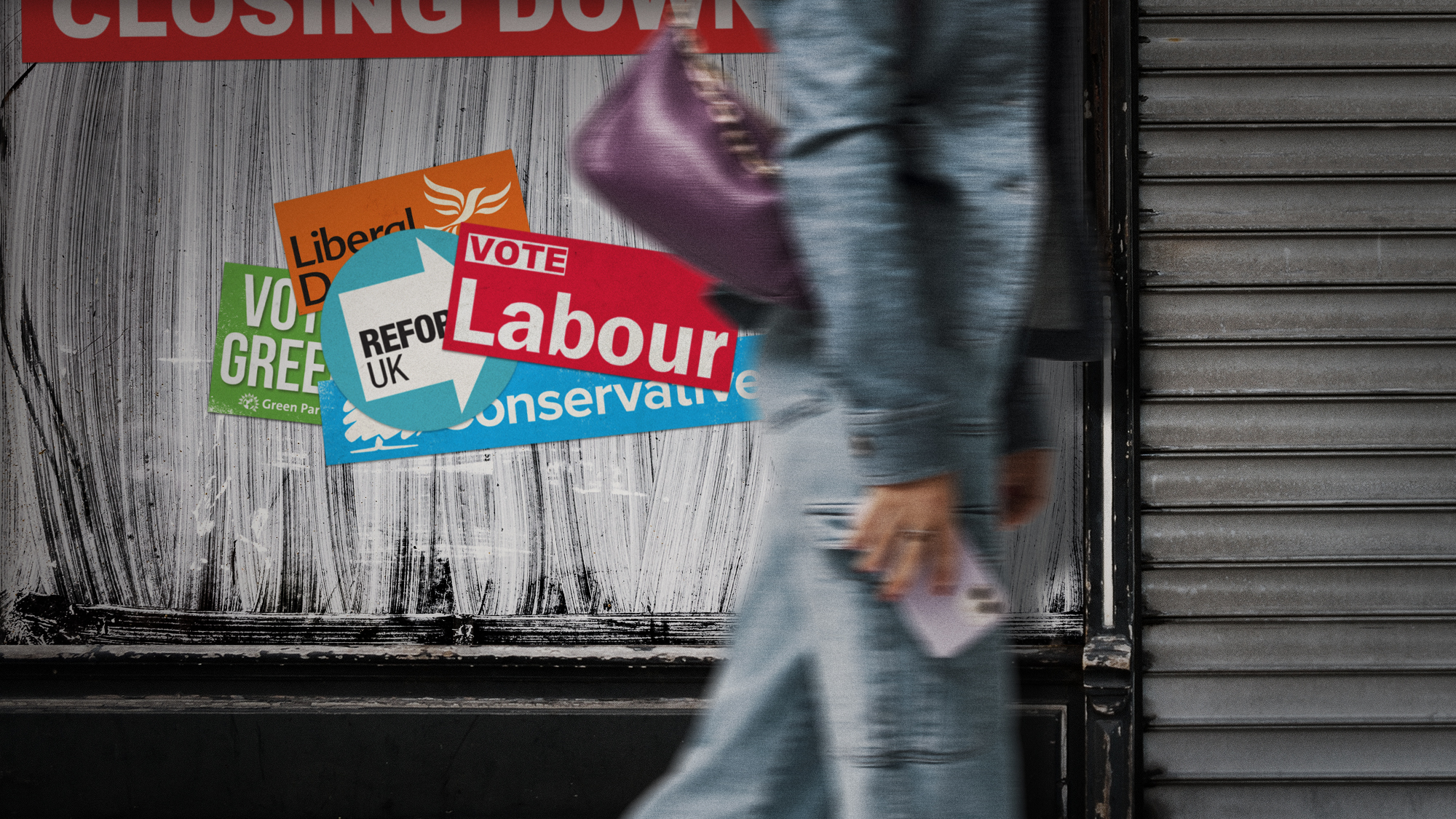

The high street: Britain’s next political battleground?

The high street: Britain’s next political battleground?In the Spotlight Mass closure of shops and influx of organised crime are fuelling voter anger, and offer an opening for Reform UK

-

Is a Reform-Tory pact becoming more likely?

Is a Reform-Tory pact becoming more likely?Today’s Big Question Nigel Farage’s party is ahead in the polls but still falls well short of a Commons majority, while Conservatives are still losing MPs to Reform

-

Asylum hotels: everything you need to know

Asylum hotels: everything you need to knowThe Explainer Using hotels to house asylum seekers has proved extremely unpopular. Why, and what can the government do about it?

-

Taking the low road: why the SNP is still standing strong

Taking the low road: why the SNP is still standing strongTalking Point Party is on track for a fifth consecutive victory in May’s Holyrood election, despite controversies and plummeting support

-

Behind the ‘Boriswave’: Farage plans to scrap indefinite leave to remain

Behind the ‘Boriswave’: Farage plans to scrap indefinite leave to remainThe Explainer The problem of the post-Brexit immigration surge – and Reform’s radical solution

-

Is Andy Burnham making a bid to replace Keir Starmer?

Is Andy Burnham making a bid to replace Keir Starmer?Today's Big Question Mayor of Manchester on manoeuvres but faces a number of obstacles before he can even run

-

What difference will the 'historic' UK-Germany treaty make?

What difference will the 'historic' UK-Germany treaty make?Today's Big Question Europe's two biggest economies sign first treaty since WWII, underscoring 'triangle alliance' with France amid growing Russian threat and US distance