52 ideas that changed the world: 37. Scientific method

As scientists rush to develop a vaccine for the coronavirus they will rely on principles developed more than 400 years ago

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

In this series, The Week looks at the ideas and innovations that permanently changed the way we see the world. This week, the spotlight is on the scientific method:

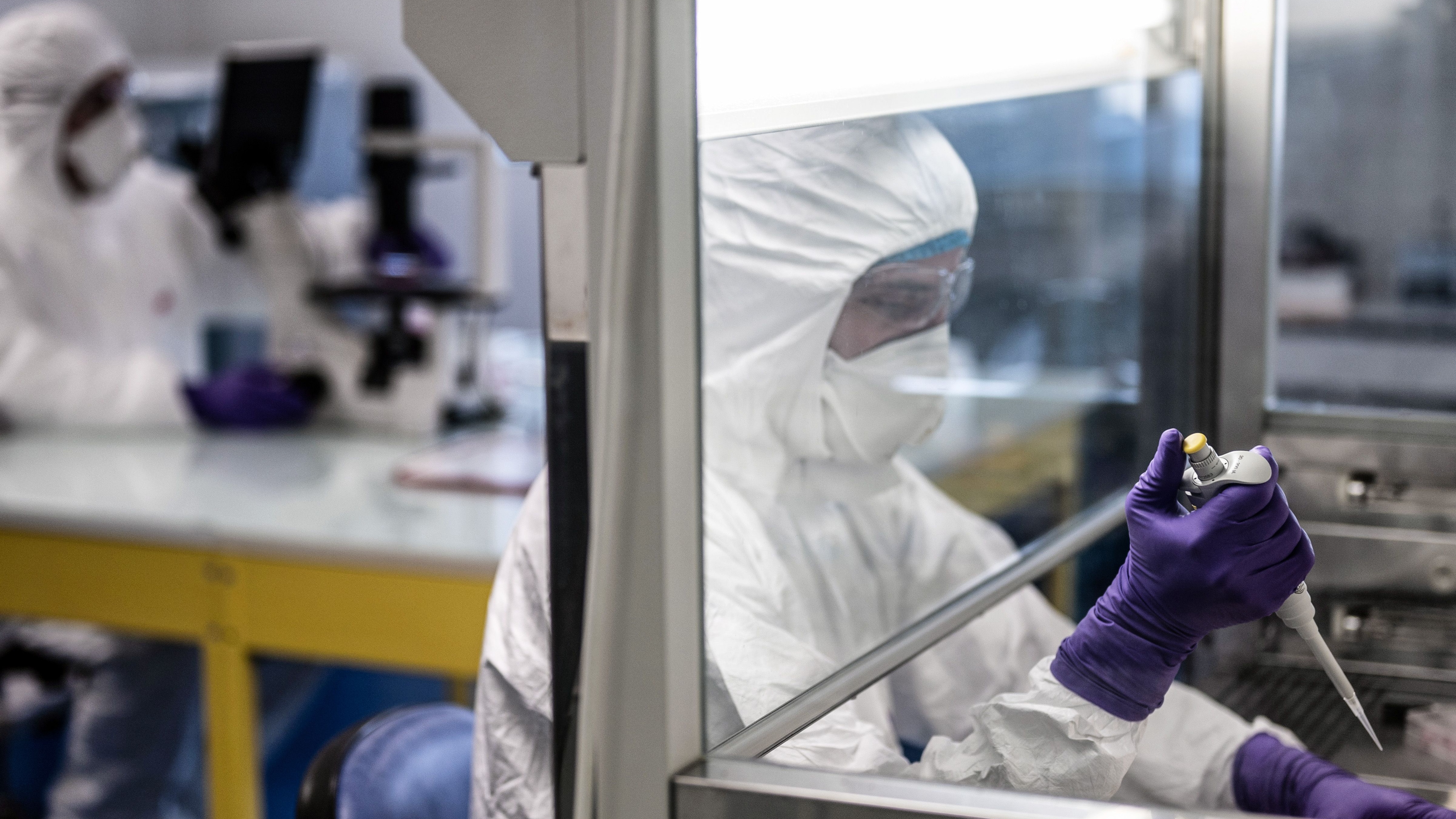

As the world scrambles to deal with the spread of the coronavirus, scientists around the world are working hard trying to devise a vaccine.

This week, a US company announced that it had begun testing a potential vaccine on animals, while much is being made of the Trump administration’s refusal to say that the drug would be affordable to all.

Article continues belowThe Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The global vaccine market is expected to grow to $60bn (£46bn) this year, but big profits are by no means guaranteed in the field, mainly because of the money and time spent on the process of getting the drug to market. This requires long periods of experimentation, during which positive and negative outcomes are carefully documented, as well as a period of monitored tests known as clinical trials.

The combination of development and testing is all part of the scientific method that leads a drug to market. In this case, the best estimate is that the drug will be available in around a year.

But where do those scientific methods come from and how did they develop?

Scientific method in 60 seconds

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

The scientific method is a process of experimentation that is used to explore observations and answer questions. The goal is essentially to discover cause and effect relationships by conducting experiments, gathering and examining the evidence, and seeing if all the available information can be combined into a logical answer.

It involves formulating a hypothesis, normally through inductive reasoning where there is at least some, though not conclusive, evidence for the observation. This is followed by experimental and measurement-based testing of the hypotheses, followed by refinement (or in the case that it was incorrect, elimination) of the original hypotheses based on the experimental findings.

Using the example of the coronavirus, The Washington Post notes that the race for a vaccine will begin with doctors hypothesising about “unproven treatments that they think stand a chance of working”. They will then document positive and negative outcomes, before moving to a more experimental “clinical trial” stage, before refining their original idea into a safe, marketable drug.

The scientific method is often thought of as a series of steps to arrive at a conclusion, but new information or thinking might cause a scientist to repeat steps at any point during the process. A process of reconsidering the scientific method is called an iterative process.

American theoretical physicist Richard Feynman described the scientific method as a combination of “observation, reason and experiment” carried out for the purpose of arriving at truth.

How did it develop?

English biologist Thomas Huxley described a “man of science” as someone who has “learned to believe in justification, not by faith, but by verification”.

This means of verification developed in the Western world during the Renaissance period, following the erosion of intellectualism that took place during the dark ages.

The 12th century was marked by a number of Western scholars engaging with the Islamic world and other regions beyond their boundaries. This led them to acquaint themselves with ancient thinkers such as Aristotle, Ptolemy and Euclid, all of whom worked in the fields of both mathematics and science, but also logic and empiricism.

Albertus Magnus and Thomas Aquinas were hugely influential for their study of scholasticism, a school of thought that championed the use of reason in exploring questions. Magnus wrote that “natural science does not consist in ratifying what others have said, but in seeking the causes of phenomena”, an early nod to the refinement stage of the modern scientific method.

Roger Bacon, an English Franciscan friar, philosopher and scientist, was a prominent voice in the 13th century. Bacon wrote that “argument is conclusive”, but that the mind may not be sure of truth, unless it finds it by the “method of experiment”. He called for an end to blind acceptance of writings, a controversial topic that greatly inspired lawyer and philosopher Francis Bacon (no relation).

Francis Bacon advocated for a new approach to scientific inquiry, which he published in 1621 as the Novum Organum Scientiarum. He called for inductive reasoning to be the foundation of scientific thinking, arguing that only a clear system of scientific inquiry would assure man’s understanding of the world.

Bacon was also inspired by the observations and experiments of Renaissance-era polymaths Nicolaus Copernicus and Galileo Galilei. Drawing on what Bacon would term “the evidence of the sense, helped and guarded by a certain process of correction”, both made great strides in laying out the workings of the solar system through observation and experimental verification.

In the late 1600s and early 1700s, Isaac Newton did much to drive what would become knows as the “scientific revolution” forward. In Principia, Newton laid out his four “rules of reasoning” including “we are to admit no more causes of natural things than such as are both true and sufficient to explain their appearances”.

Newton’s work became a model that other scientists sought to emulate, and were built upon in 1843, in John Stuart Mill’s “methods”. These were outlined in A System of Logic, and saw the philosopher explain five techniques of “experimental reasoning” to decipher “what factors play a role in causing a specific effect”. This set in place a method for evaluating evidence to come to logical conclusions that, drawing on the work of Newton, would go on to influence the discovery of cell theory.

Louis Pasteur’s work to disprove that cells could be “spontaneously generated” solidified the steps of the modern scientific method. Pasteur’s experiments with long-necked flasks, now taught extensively in schools, employed all of the hallmarks of modern scientific work, beginning with a hypothesis and testing that hypothesis using a carefully controlled experiment.

Pasteur also employed the same scientific method in the development of vaccines, a contribution that led to the formation of immunology. Pasteur’s first important discovery in the study of vaccination came in 1879 and concerned a disease called chicken cholera.

But it was only in the 20th century that an understanding was gained of the “formation, mobilisation, action, and interaction of antibodies”. This led to the discovery of vaccinations for a range of previously fatal or deforming illnesses including polio, tetanus and measles.

Each of those new vaccinations was developed using the same scientific method outlined by Pasteur’s work on cell theory, with 20th-century scientists like the Polish inventor of the polio vaccine, Hilary Koprowski, testing and observing various vaccination attempts before refining their ideas through data collection.

In the experimental period of developing a polio vaccine, Koprowski toyed with both live and killed virus vaccines, discovering that the live vaccine was more powerful, since it could provide lifelong immunity.

As the BBC notes, the work on a new coronavirus vaccine is using newer, and less tested, approaches called “plug and play” vaccines, replicating the type of experiments and data collection carried out by Koprowski in testing different forms of vaccine.

“Some vaccine scientists are lifting small sections of the coronavirus’s genetic code and putting it into other, completely harmless, viruses,” the BBC reports. “Now you can ‘infect’ someone with the harmless bug and in theory give some immunity to the coronavirus.”

The coronavirus vaccine, when it arrives, will be developed through the same method of experimentation, observation and refinement laid out during the Renaissance and built on by generations of scientists since. Best estimates at the moment suggest that initial trials of the potential vaccine could begin in April, but the process of testing and approval could last up to a year.

How did it change the world?

The scientific method attempts to minimise the influence of bias or prejudice in the experimenter. It provides an objective, standardised approach to conducting experiments and, in doing so, improves their results.

English psychologist Peter Wason wrote in the 1960s about the phenomenon of “confirmation bias” (itself a concept developed through scientific method) in which individuals favour information that confirms previously existing beliefs.

The scientific method attempts to nullify this, by using a standardised approach to investigation, that limits the influence of personal, preconceived notions.

The outlining of the scientific method launched the “scientific revolution” in the 16th century, giving rise to developments that transformed the views of society about nature and ushering in 400 years of scientific development.

Joe Evans is the world news editor at TheWeek.co.uk. He joined the team in 2019 and held roles including deputy news editor and acting news editor before moving into his current position in early 2021. He is a regular panellist on The Week Unwrapped podcast, discussing politics and foreign affairs.

Before joining The Week, he worked as a freelance journalist covering the UK and Ireland for German newspapers and magazines. A series of features on Brexit and the Irish border got him nominated for the Hostwriter Prize in 2019. Prior to settling down in London, he lived and worked in Cambodia, where he ran communications for a non-governmental organisation and worked as a journalist covering Southeast Asia. He has a master’s degree in journalism from City, University of London, and before that studied English Literature at the University of Manchester.