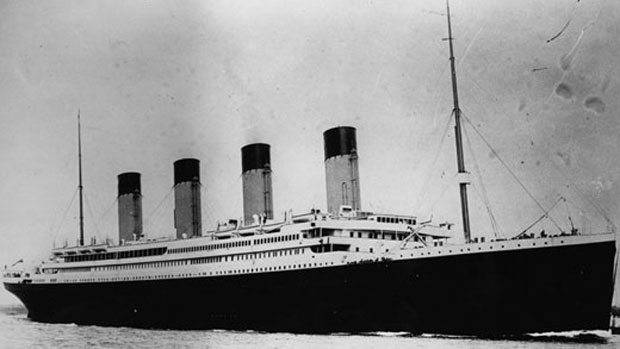

How the discovery of the Titanic's wreck proved fiction wrong

The discovery of the Titanic thirty years ago today shattered years of myth and surmise

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

By Brian Edwards

On 1 September 1985, the wreck of the RMS Titanic was discovered by an American-French team two miles below the sea and 370 miles off the coast of Newfoundland. The discovery shattered years of myth, surmise and fiction about the lost luxury liner.

The Titanic had been resting there undisturbed since the evening of 14 April 1912 when the ship struck an iceberg and sank during its maiden voyage from Southampton to New York.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Around 1,500 people perished, more than half of the 2,224 passengers and crew.

Many attempts were made to find the wreck before Dr Robert Ballard and his team finally tracked it down in 1985. Most of the searches were unsuccessful because the location data transmitted at the time of the sinking was incorrect. Searching for the wreck with sonar alone also proved fruitless. The success of Ballard and his team was partly down to their pioneering use of a remote controlled deep-sea submersible which transmitted pictures back to the surface.

The team discovered the wreckage was made up of five separate sites across a three by five mile debris field. The main two sites were the prow and stern of the ship, which was split in two as it sank, and which now lie about a third of a mile apart.

Both sites are slowly being consumed by bacteria which are eating the metal and forming what scientists refer to as "rusticles".

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

For many of us, the sinking of The Titanic is synonymous with James Cameron's 1997 blockbuster Titanic, which remains the second highest grossing film of all time.

In his highly fictionalised account, there are numerous glaring historical mistakes.

In the movie, modern light bulbs in hand torches are shown, pencils that weren't yet in production are used and Leonardo DiCaprio's Jack talks enthusiastically about riding the roller coaster on Santa Monica Pier, even though that particular roller coaster wouldn't be built for another four years. In one scene, a Sigmund Freud theorem is discussed, eight years before it was actually published.

Such minor quibbles don't really spoil the storytelling but the suggestion that Picasso's Les Demoiselles d'Avignon went down with the ship may be a step too far. The painting currently hangs in the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

The producers of the film also had to apologise to the descendants of the real-life Officer William Murdoch, who is shown in the movie shooting two escaping passengers before killing himself. There was no proof that anything similar occurred in reality.

Where the film is usually praised, however, is in its depiction of the sinking, and the toll this had on the ship itself which, over the night of the 14th and into the morning of the 15th April 1912, took just over two and a half hours.

Although the real wreck was featured extensively in the movie, lending a spooky realism to scenes featuring the rusted watery remains and the sets that had been recreated from contemporary photographs, it's only very recently that detailed mapping of the wreck has proved that the sinking depicted in the film didn't in fact take place as shown.

In 2010, a multi-million pound endeavour known as The Titanic Mapping Project was launched by the legal stewards of the wreckage, RMS Titanic Inc. It took nearly five years to complete.

It aimed to be the most accurate recording of all the available data from the sea floor possible – measuring the size, state and location of all of the debris (even the items retrieved to the surface) using precise sonar imaging as well as hi-res photography by underwater robots to eventually create a massive picture of what the whole site looks like. The recent documentary Drain The Titanic showed the 3D model they created from their results.

What the scientists looking at the combined 37 terabytes of data of the debris field discovered was that the widely held opinion about what had happened to the ship was incorrect. And, unfortunately, that thing was depicted in James Cameron's movie.

The film shows Titanic sinking prow first, then the stern being pulled out of the water, tearing apart from the rest of the ship and sinking. The tear did happen, just not in the way shown.

The Titanic Mapping Project showed the debris field around the wreck of the stern was relatively small in size. From the depth it was embedded in the mud the speed it was travelling could also be calculated. Additionally circular markings on the seabed show it had been spinning around in a circle at the time of impact. Combined these pieces of evidence proved that the Titanic had categorically not been torn apart above the surface as shown in the movie. Quite simply if the ship had been torn apart above the surface as depicted, both the scatter pattern and the debris field itself would have been many magnitudes larger.

Had Titanic's director James Cameron been aware of this at the time of production, it might have been a very different film.

The new research shows that if you want to know history as it really happened, you should trust science and archaeology, not Hollywood.

-

Local elections 2026: where are they and who is expected to win?

Local elections 2026: where are they and who is expected to win?The Explainer Labour is braced for heavy losses and U-turn on postponing some council elections hasn’t helped the party’s prospects

-

6 of the world’s most accessible destinations

6 of the world’s most accessible destinationsThe Week Recommends Experience all of Berlin, Singapore and Sydney

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

Epstein files topple law CEO, roil UK government

Epstein files topple law CEO, roil UK governmentSpeed Read Peter Mandelson, Britain’s former ambassador to the US, is caught up in the scandal

-

Iran and US prepare to meet after skirmishes

Iran and US prepare to meet after skirmishesSpeed Read The incident comes amid heightened tensions in the Middle East

-

Israel retrieves final hostage’s body from Gaza

Israel retrieves final hostage’s body from GazaSpeed Read The 24-year-old police officer was killed during the initial Hamas attack

-

China’s Xi targets top general in growing purge

China’s Xi targets top general in growing purgeSpeed Read Zhang Youxia is being investigated over ‘grave violations’ of the law

-

Panama and Canada are negotiating over a crucial copper mine

Panama and Canada are negotiating over a crucial copper mineIn the Spotlight Panama is set to make a final decision on the mine this summer

-

Why Greenland’s natural resources are nearly impossible to mine

Why Greenland’s natural resources are nearly impossible to mineThe Explainer The country’s natural landscape makes the task extremely difficult

-

Iran cuts internet as protests escalate

Iran cuts internet as protests escalateSpeed Reada Government buildings across the country have been set on fire

-

US nabs ‘shadow’ tanker claimed by Russia

US nabs ‘shadow’ tanker claimed by RussiaSpeed Read The ship was one of two vessels seized by the US military