Psychosis: is cannabis good or bad for mental health?

Heaviest users of cannabis around four times as likely to develop schizophrenia than non-users

There has been a recent global rise in “green fever”, with various jurisdictions either decriminalising or legalising cannabis.

But alongside relaxing the rules comes concern about the health implications of cannabis use. We often hear of a link between cannabis use and psychosis. So how strong is the link, and who is at risk?

What is psychosis?

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

There’s consistent evidence showing a relationship over time between heavy or repeated cannabis use (or those diagnosed with cannabis use disorder) and an experience of psychosis for the first time.

Psychotic disorders are severe mental health conditions. They’re characterised by a “loss of contact with reality”, where the individual loses the ability to distinguish what’s real from what’s not. Psychotic symptoms can include visual hallucinations, hearing voices, or pervasive delusional thinking.

These can often present as a “psychotic episode” – which is a relatively sudden worsening of psychotic symptoms over a short time-frame, frequently resulting in hospitalisation.

The heaviest users of cannabis are around four times as likely to develop schizophrenia (a psychotic disorder that affects a person’s ability to think, feel and behave clearly) than non-users. Even the “average cannabis user” (for which the definition varies from study to study) is around twice as likely as a non-user to develop a psychotic disorder.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Furthermore, these studies found a causal link between tetrahydrocannabinol (THC - the plant chemical which elicits the “stoned” experience) and psychosis. This means the link is not coincidental, and one has actually caused the other.

Who is at risk?

People with certain gene variants seem to be at higher risk. However our understanding of these factors is still limited, and we’re unable to use genetic information alone to determine if someone will or won’t develop psychosis from cannabis use.

Those with these genetic variants who have also experienced childhood trauma, or have a paranoid personality type, are even more at-risk. So too are adolescents and young adults, who have growing brains and are at an age where schizophrenia is more likely to manifest.

The type of cannabis material being used (or the use of synthetic cannabinoids, known as “spice”) may also increase the risk of psychosis. As mentioned above, this is due to the psychological effects of the chemical THC (one of over 140 cannabinoids found in the plant).

This compound may actually mimic the presentation of psychotic symptoms, including paranoia, sensory alteration, euphoria, and hallucinations. In laboratory-based research, even healthy people may exhibit increased symptoms of psychosis when given THC compounds, with more severe effects observed in people with schizophrenia.

Many cannabis strains contain high amounts of THC, found in plant varieties such as one called “skunk”. These are popular with consumers due to the “high” it elicits. However with this goes the increased risk of paranoia, anxiety, and psychosis.

But can’t cannabis also be good for mental health?

Ironically, one compound found in cannabis may actually be beneficial in treating psychosis. In contrast to THC, a compound called cannabidiol (CBD) may provide a buffering effect to the potentially psychosis-inducing effects of THC.

This may occur in part due to its ability to partially block the same brain chemical receptor THC binds with. CBD can also inhibit the breakdown of a brain chemical called “anandamide,” which makes us feel happy. Incidentally, anandamide is also found in chocolate and is aptly named after the Sanskrit word meaning “bliss”.

CBD extracted from cannabis and used in isolation is well-tolerated with minimal psychoactive effects. In other words, it doesn’t make a person feel “high”. Some studies have found CBD is actually beneficial in improving the symptoms of schizophrenia. But one more recent study showed no difference in the effects of CBD compared to a dummy pill on symptoms of schizophrenia.

Perhaps this means CBD benefits a particular biological sub-type of schizophrenia, but we’d need further study to find out.

Would legalising make a difference?

It’s important to note most studies finding a causal link between cannabis use and psychosis examined the use of illicit cannabis, usually from unknown origins. This means the levels of THC were unrestricted, and there’s a possibility of synthetic adulterants, chemical residues, heavy metals or other toxins being present due to a lack of quality assurance practices.

In the future, it’s possible that standardised novel “medicinal cannabis” formulations (or isolated compounds) may have negligible effects on psychosis risk.

Until then though, we can safely say given the current weight of evidence, illicit cannabis use can increase the risk of an acute psychotic episode. And this subsequently may also increase the chances of developing schizophrenia. This is particularly true when high-THC strains (or synthetic versions) are used at high doses in growing adolescent brains.

Jerome Sarris, Professor of Integrative Mental Health; NICM Deputy Director, Western Sydney University and Joe Firth, Postdoctoral Research Fellow at NICM Health Research Institute, Western Sydney University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

-

Grok in the crosshairs as EU launches deepfake porn probe

Grok in the crosshairs as EU launches deepfake porn probeIN THE SPOTLIGHT The European Union has officially begun investigating Elon Musk’s proprietary AI, as regulators zero in on Grok’s porn problem and its impact continent-wide

-

‘But being a “hot” country does not make you a good country’

‘But being a “hot” country does not make you a good country’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

Why have homicide rates reportedly plummeted in the last year?

Why have homicide rates reportedly plummeted in the last year?Today’s Big Question There could be more to the story than politics

-

RFK Jr. sets his sights on linking antidepressants to mass violence

RFK Jr. sets his sights on linking antidepressants to mass violenceThe Explainer The health secretary’s crusade to Make America Healthy Again has vital mental health medications on the agenda

-

The app tackling porn addiction

The app tackling porn addictionUnder the Radar Blending behavioural science with cutting-edge technology, Quittr is part of a growing abstinence movement among men focused on self-improvement

-

Scientists have identified 4 distinct autism subtypes

Scientists have identified 4 distinct autism subtypesUnder the radar They could lead to more accurate diagnosis and care

-

'Wonder drug': the potential health benefits of creatine

'Wonder drug': the potential health benefits of creatineThe Explainer Popular fitness supplement shows promise in easing symptoms of everything from depression to menopause and could even help prevent Alzheimer's

-

Fly like a breeze with these 5 tips to help cope with air travel anxiety

Fly like a breeze with these 5 tips to help cope with air travel anxietyThe Week Recommends You can soothe your nervousness about flying before boarding the plane

-

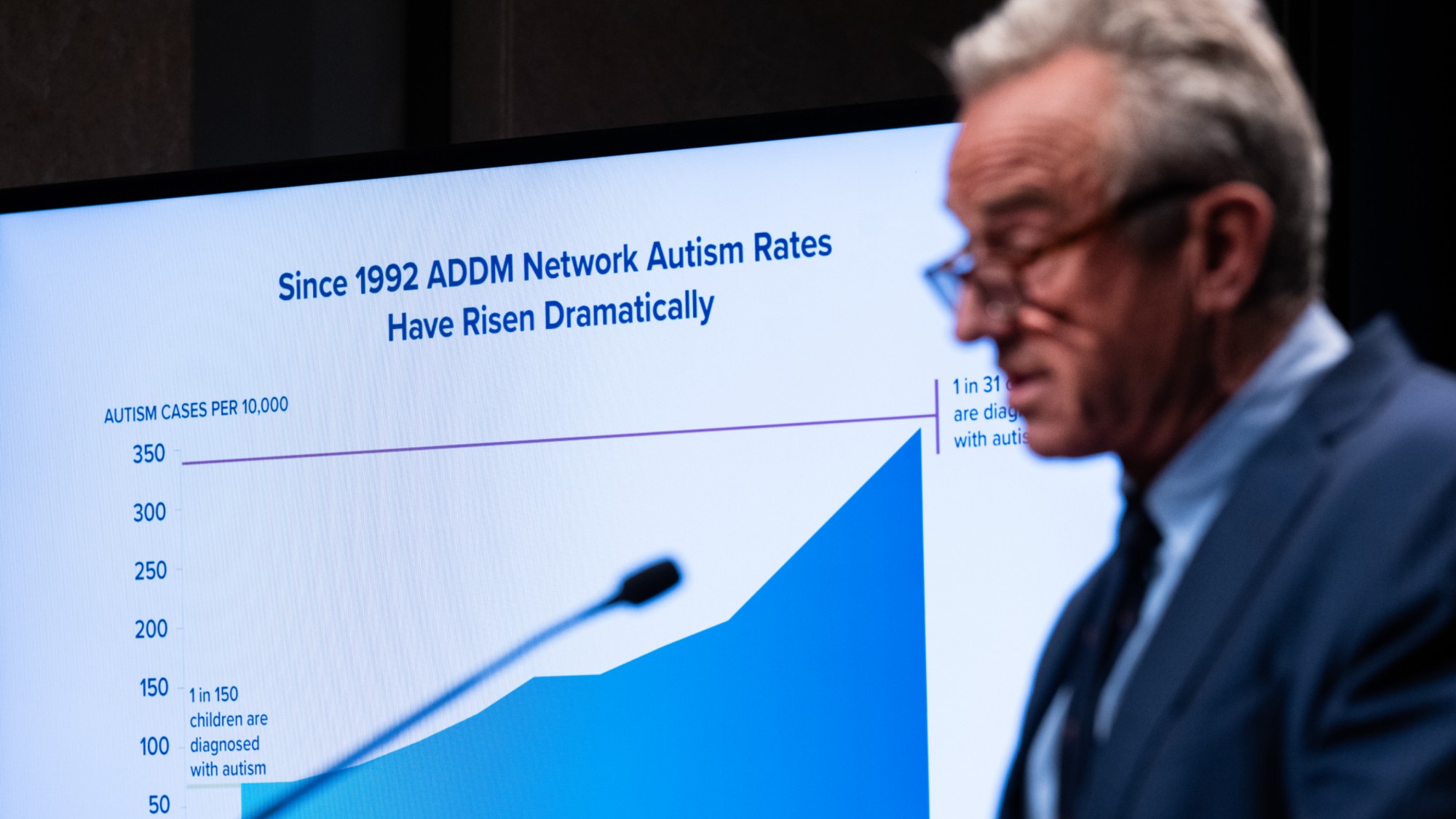

RFK Jr.'s focus on autism draws the ire of researchers

RFK Jr.'s focus on autism draws the ire of researchersIn the Spotlight Many of Kennedy's assertions have been condemned by experts and advocates

-

Mental health: a case of overdiagnosis?

Mental health: a case of overdiagnosis?Talking Point Issues at 'the milder end of the spectrum' may be getting wrongly pathologised

-

Washwood Heath: Birmingham's pioneering neighbourhood health service

Washwood Heath: Birmingham's pioneering neighbourhood health serviceIn the Spotlight NHS England chair says there is a 'really good argument this is the model for the future'