Is internet addiction real?

Up to 8% of Americans ‘diagnosed’ as growing digital dependency spawns host of new treatment programmes

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Internet addiction has become such a problem in the US that special treatment programmes have begun to spring up to help wean young people off their digital dependency.

Neither the World Health Organisation not the American Psychiatric Association recognise internet addiction as a disorder, “but a growing number of medical experts has begun taking the condition seriously”, says Tech Times.

Characterised by a loss of control over internet use and disregard for the consequences of it, Reuters says it now “affects up to 8% of Americans and is becoming more common around the world”.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

A recent survey in South Korea, which is thought to have the world’s highest rate of problematic internet use among both children and adults, put the share of three-to nine-year-olds at high risk of smartphone and internet addiction at 1.2% and that of teenagers at 3.5%.

The Economist on iNews says “that may not seem a lot, but when it happens the effects can be devastating. Some of these children are on their phones for at least eight hours a day and lose interest in offline life. Having tried and failed to wean them from their devices, their desperate parents turn to the government, which offers various kinds of counselling, therapy and, in extreme cases, remedial boot camps.”

Kimberly Young, who founded the Center for Internet Addiction in 1995, told Reuters psychiatrists are seeing more and more cases of internet dependency, prompting a wave of new treatments across the US.

One such centre offers an in-patient treatment called “Reboot”, which specifically targets internet addiction in children from 11 to 17 years old.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

According to Tech Times, the 28-day programme “helps those who have addictions that include online gaming, online gambling, social media, pornography, and sexting — often to escape the symptoms of mental illnesses such as depression”.

Reboot’s clinical director of addiction services, Chris Tuell, says the internet, while not officially recognised as an addictive substance, similarly hijacks the brain’s reward system by triggering the release of pleasure-inducing chemicals and is accessible from an early age.

He says he started the programme after seeing several cases where young people were using the internet to “self-medicate” instead of drugs and alcohol.

However, because the internet is ubiquitous and essential in schools, homes and the workplace, the answer is not about getting sober but rather moderation.

But not all are convinced.

“Although there are clear instances of overuse, terms like 'addiction' or 'compulsive use' may be overblown,” says The Economist. “There is no real evidence that spending too much time online severely impairs the user’s life in the longer term, as drug abuse often does.”

“The relationship between the use of digital technology and children’s mental health, broadly speaking, appears to be u-shaped,” says the magazine. “Researchers have found that moderate use is beneficial, whereas either no use at all or extreme use could be harmful.”

In the UK, the Daily Mirror reports that children as young as 11 are being taken into care over fears they are addicted to gaming.

An investigation by the paper found 13 kids were removed from families over the course of two months due to concerns over computer overuse.

“In what is believed to be the first cases of their kind, some of the youngsters were taken away because of their own addiction, while others were neglected by parents playing the games too much themselves,” says the Daily Mail.

Last year, the WHO formally recognised Gaming Disorder following years of research in China, South Korea and Taiwan, where doctors have called it a public health crisis.

WHO spokesman Tarik Jasarevic said internet addiction is the subject of “intensive research” and consideration for future classification.

-

Local elections 2026: where are they and who is expected to win?

Local elections 2026: where are they and who is expected to win?The Explainer Labour is braced for heavy losses and U-turn on postponing some council elections hasn’t helped the party’s prospects

-

6 of the world’s most accessible destinations

6 of the world’s most accessible destinationsThe Week Recommends Experience all of Berlin, Singapore and Sydney

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

Moltbook: The AI-only social network

Moltbook: The AI-only social networkFeature Bots interact on Moltbook like humans use Reddit

-

Are Big Tech firms the new tobacco companies?

Are Big Tech firms the new tobacco companies?Today’s Big Question A trial will determine whether Meta and YouTube designed addictive products

-

Is social media over?

Is social media over?Today’s Big Question We may look back on 2025 as the moment social media jumped the shark

-

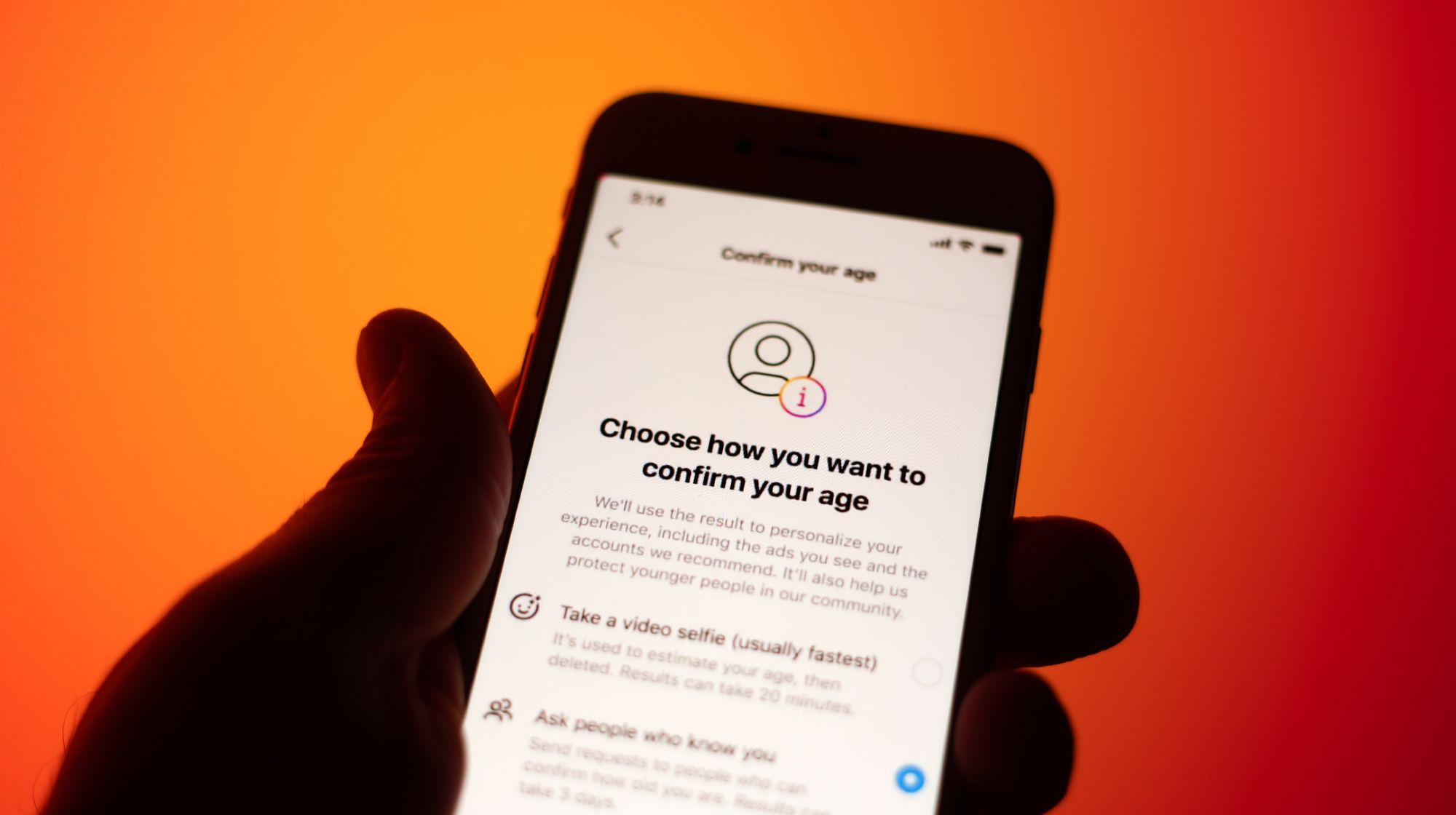

Australia’s teen social media ban takes effect

Australia’s teen social media ban takes effectSpeed Read Kids under age 16 are now barred from platforms including YouTube, TikTok, Instagram, Facebook, Snapchat and Reddit

-

Trump allies reportedly poised to buy TikTok

Trump allies reportedly poised to buy TikTokSpeed Read Under the deal, U.S. companies would own about 80% of the company

-

What an all-bot social network tells us about social media

What an all-bot social network tells us about social mediaUnder The Radar The experiment's findings 'didn't speak well of us'

-

Broken brains: The social price of digital life

Broken brains: The social price of digital lifeFeature A new study shows that smartphones and streaming services may be fueling a sharp decline in responsibility and reliability in adults

-

Supreme Court allows social media age check law

Supreme Court allows social media age check lawSpeed Read The court refused to intervene in a decision that affirmed a Mississippi law requiring social media users to verify their ages