When Khomeini said no to Iranian nukes

In an exclusive interview, a top Iranian official says that Khomeini personally stopped him from building Iran's WMD program

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The nuclear negotiations between six world powers and Iran, which are now nearing their November deadline, remain deadlocked over U.S. demands that Iran dismantle the bulk of its capacity to enrich uranium. The demand is based on the suspicion that Iran has worked secretly to develop nuclear weapons in the past and can't be trusted not to do so again.

Iran argues that it has rejected nuclear weapons as incompatible with Islam and cites a fatwa of Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei as proof. American and European officials remain skeptical, however, that the issue is really governed by Shiite Islamic principles. They have relied instead on murky intelligence that has never been confirmed about an alleged covert Iranian nuclear weapons program.

But the key to understanding Iran's policy toward nuclear weapons lies in a historical episode during its eight-year war with Iraq. The story, told in full for the first time here, explains why Iran never retaliated against Iraq's chemical weapons attacks on Iranian troops and civilians, which killed 20,000 Iranians and severely injured 100,000 more. And it strongly suggests that the Iranian leadership's aversion to developing chemical and nuclear weapons is deep-rooted and sincere.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

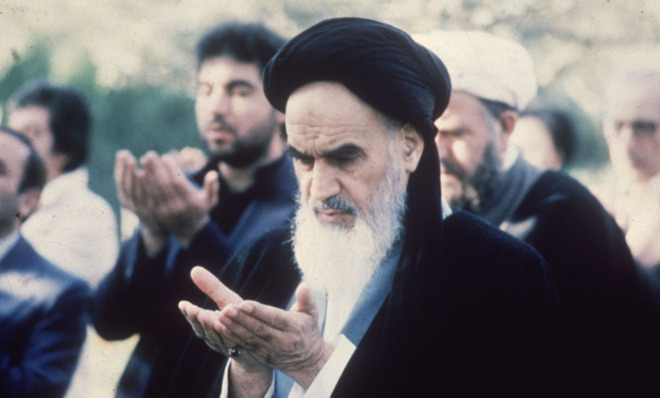

A few Iranian sources have previously pointed to a fatwa by the Islamic Republic's first supreme leader, Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, prohibiting chemical weapons as the explanation for why Iran did not deploy these weapons during the war with Iraq. But no details have ever been made public on when and how Khomeini issued such a fatwa, so it has been ignored for decades.

Now, however, the wartime chief of the Iranian ministry responsible for military procurement has provided an eyewitness account of Khomeini's ban not only on chemical weapons, but on nuclear weapons as well. In an interview with me in Tehran in late September, Mohsen Rafighdoost, who served as minister of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) throughout the eight-year war, revealed that he had proposed to Khomeini that Iran begin working on both nuclear and chemical weapons — but was told in two separate meetings that weapons of mass destruction are forbidden by Islam. I sought the interview with Rafighdoost after learning of an interview he had with Mehr News Agency in January in which he alluded to the wartime meetings with Khomeini and the supreme leader's forbidding chemical and nuclear weapons.

(More from Foreign Policy: This is why you can't have nice guns)

Rafighdoost was jailed under the Shah for dissident political activity and became a point of contact for anti-Shah activists when he got out of prison in 1978. When Khomeini returned to Tehran from Paris after the 1979 Islamic Revolution, Rafighdoost became his bodyguard and head of his security detail. He was also a founding member of the IRGC and was personally involved in every major military decision taken by the corps during the Iran-Iraq War, including the initiation of Iran's ballistic missile program and creation of Hezbollah.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Despite his IRGC background, however, Rafighdoost has embraced the pragmatism of President Hassan Rouhani's government. In October 2013, he recalled in an interview that Khomeini had dissuaded him from setting up the IRGC's headquarters at the former U.S. Embassy in Tehran.

"Why do you want to go there?" Rafighdoost recalled Khomeini as saying. "Are our disputes with the U.S. supposed to last a thousand years? Do not go there."

Rafighdoost received me in his modest office at the Noor Foundation, of which he has been chairman since 1999. Looking younger than his 74 years, he still has the stocky build of a bodyguard and bright, alert eyes.

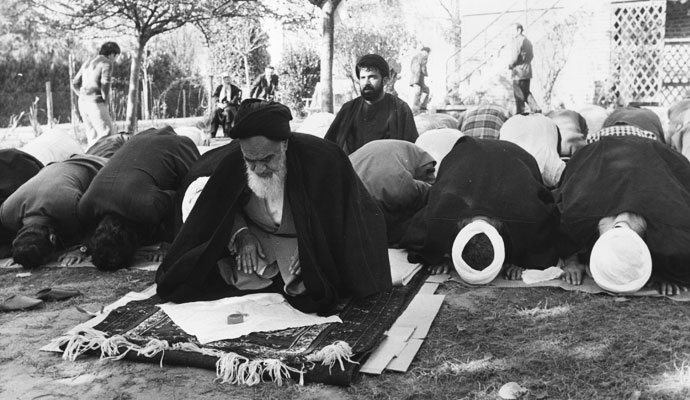

Saddam Hussein's Iraq began using chemical weapons against Iranian troops after Iran repelled the initial Iraqi attack and began a counterattack inside Iraq. The Iraqis considered chemical weapons to be the only way to counter Iran's superiority in manpower. Iranian doctors first documented symptoms of mustard gas from Iraqi chemical attacks against Iranian troops in mid-1983. However, Rafighdoost said, a dramatic increase in Iraqi gas attacks occurred during an Iranian offensive in southern Iraq in February and March 1984. The attacks involved both mustard gas and the nerve gas tabun, which prompted him to take a major new initiative in his war planning.

Rafighdoost told me he asked some foreign governments for assistance, including weapons, to counter the chemical-war threat, but all of them rejected his requests. This prompted him to decide that his ministry would have to produce everything Iran needed for the war. "I personally gathered all the researchers who had any knowledge of defense issues," he recalled. He organized groups of specialists to work on each category of military need — one of which was called "chemical, biological, and nuclear."

Rafighdoost prepared a report on all the specialized groups he had formed and went to discuss it with Khomeini, hoping to get his approval for work on chemical and nuclear weapons. The supreme leader met him accompanied only by his son, Ahmad, who served as chief of staff, according to Rafighdoost. "When Khomeini read the report, he reacted to the chemical-biological-nuclear team by asking, 'What is this?'" Rafighdoost recalled.

Khomeini ruled out development of chemical and biological weapons as inconsistent with Islam.

"Imam told me that, instead of producing chemical or biological weapons, we should produce defensive protection for our troops, like gas masks and atropine," Rafighdoost said.

Rafighdoost also told Khomeini that the group had "a plan to produce nuclear weapons." That could only have been a distant goal in 1984, given the rudimentary state of Iran's nuclear program. At that point, Iranian nuclear specialists had no knowledge of how to enrich uranium and had no technology with which to do it. But in any case, Khomeini closed the door to such a program. "We don't want to produce nuclear weapons," Rafighdoost recalls the supreme leader telling him.

Khomeini instructed him instead to "send these scientists to the Atomic Energy Organization," referring to Iran's civilian nuclear-power agency. That edict from Khomeini ended the idea of seeking nuclear weapons, according to Rafighdoost.

(More from Foreign Policy: Terrorists among us)

The chemical-warfare issue took a new turn in late June 1987, when Iraqi aircraft bombed four residential areas of Sardasht, an ethnically Kurdish city in Iran, with what was believed to be mustard gas. It was the first time Iran's civilian population had been targeted by Iraqi forces with chemical weapons, and the population was completely unprotected. Of 12,000 inhabitants, 8,000 were exposed, and hundreds died.

As popular fears of chemical attacks on more Iranian cities grew quickly, Rafighdoost undertook a major initiative to prepare Iran's retaliation. He worked with the Defense Ministry to create the capability to produce mustard gas weapons.

Rafighdoost was obviously hoping that the new circumstances of Iraqi chemical weapons attacks on Iranian civilians would cause Khomeini to have a different view of the issue. He made it clear to me that Khomeini didn't know about the production of the two chemicals for mustard gas weapons until it had taken place. "In the meeting, I told Imam we have high capability to produce chemical weapons," he recalled. Rafighdoost then asked Khomeini for his view on "this capability to retaliate."

Iran's permanent representative to the Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW) disclosed the details of Rafighdoost's chemical weapons program in a document provided to the U.S. delegation to the OPCW on May 17, 2004. It was later made public by WikiLeaks, which published a U.S. diplomatic cable reporting on its contents. The document shows that the two ministries had procured the chemical precursors for mustard gas and in September 1987 began to manufacture the chemicals necessary to produce a weapon — sulfur mustard and nitrogen mustard. But the document also indicated that the two ministries did not "weaponize" the chemicals by putting them into artillery shells, aerial bombs, or rockets.

The supreme leader was unmoved by the new danger presented by the Iraqi gas attacks on civilians. "It doesn't matter whether it is on the battlefield or in cities; we are against this," he told Rafighdoost. "It is haram [forbidden] to produce such weapons. You are only allowed to produce protection."

Invoking the Islamic Republic's claim to spiritual and moral superiority over the secular Iraqi regime, Rafighdoost recalls Khomeini asking rhetorically, "If we produce chemical weapons, what is the difference between me and Saddam?"

Khomeini's verdict spelled the end of the IRGC's chemical weapons initiative. "Even after Sardasht, there was no way we could retaliate," Rafighdoost recalled. The 2004 Iranian document confirms that production of two chemicals ceased, the buildings in which they were stored were sealed in 1988, and the production equipment was dismantled in 1992.

Khomeini also repeated his edict forbidding work on nuclear weapons, telling him, "Don't talk about nuclear weapons at all."

Rafighdoost understood Khomeini's prohibition on the use or production of chemical, biological, or nuclear weapons as a fatwa — a judgment on Islamic jurisprudence by a qualified Islamic scholar. It was never written down or formalized, but that didn't matter, because it was issued by the "guardian jurist" of the Islamic state — and was therefore legally binding on the entire government. "When Imam said it was haram [forbidden], he didn't have to say it was fatwa," Rafighdoost explained.

Rafighdoost did not recall the date of that second meeting with Khomeini, but other evidence strongly suggests that it was in December 1987. Iranian Prime Minister Mir Hossein Mousavi said in a late December 1987 speech that Iran "is capable of manufacturing chemical weapons" and added that a "special section" had been set up for "offensive chemical weapons." But Mousavi refrained from saying that Iran actually had chemical weapons, and he hinted that Iran was constrained by religious considerations. "We will produce them only when Islam allows us and when we are compelled to do so," he said.

A few days after Mousavi's speech, a report in the London daily The Independent referred to a Khomeini fatwa against chemical weapons. Former Iranian nuclear negotiator Seyed Hossein Mousavian, now a research scholar at Princeton University, confirmed for this article that Khomeini's fatwa against chemical and nuclear weapons, which accounted for the prime minister's extraordinary statement, was indeed conveyed in the meeting with Rafighdoost.

In February 1988, Saddam stepped up his missile attacks on urban targets in Iran. He also threatened to arm his missiles with chemical weapons, which terrified hundreds of thousands of Iranians. Between a third and a half of the population of Tehran evacuated the city that spring in a panic.

Khomeini's fatwa not only forced the powerful IRGC commander to forgo the desired response to Iraqi chemical weapons attacks, but the fatwa made it all but impossible for Iran to continue the war. Although Khomeini had other reasons for what he called "the bitter decision" to accept a cease-fire with Iraq in July 1988, the use of these devastating tools factored into his decision. In a letter explaining his decision, Khomeini said he was consenting to the cease-fire "in light of the enemy's use of chemical weapons and our lack of equipment to neutralize them."

(More from Foreign Policy: What does China mean by 'rule of law'?)

Khomeini's Islamic ruling against all weapons of mass destruction, including nuclear weapons, was continued by Ali Khamenei, who had served as president under Khomeini and succeeded him as supreme leader in 1989. Iran began publicizing Khamenei's fatwa against nuclear weapons in 2004, but commentators and news media in the United States and Europe have regarded it as a propaganda ploy not to be taken seriously.

The analysis of Khamenei's fatwa has been flawed not only due to a lack of understanding of the role of the "guardian jurist" in the Iranian political-legal system, but also due to ignorance of the history of Khamenei's fatwa. A crucial but hitherto unknown fact is that Khamenei had actually issued the anti-nuclear fatwa without any fanfare in the mid-1990s in response to a request from an official for his religious opinion on nuclear weapons. Mousavian recalls seeing the letter in the office of the Supreme National Security Council, where he was head of the Foreign Relations Committee from 1997 to 2005. The Khamenei letter was never released to the public, apparently reflecting the fact that the government of then President Ali Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani had been arguing against nuclear weapons for years on strategic grounds, so publicizing the fatwa appeared unnecessary at that point.

Since 2012, the official stance of U.S. President Barack Obama's administration has been to welcome the existence of Khamenei's anti-nuclear fatwa. Obama even referred to it in his U.N. General Assembly speech in September 2013. But it seems clear that Obama's advisors still do not understand the fatwa's full significance: Secretary of State John Kerry told journalists in July, "The fatwa issued by a cleric is an extremely powerful statement about intent," but then added, "It is our need to codify it."

That statement, like most of the commentary on Khamenei's fatwa against nuclear weapons, has confused fatwas issued by any qualified Muslim scholar with fatwas by the supreme leader on matters of state policy. The former are only relevant to those who follow the scholar's views; the latter, however, are binding on the state as a whole in Iran's Shiite Islam-based political system, holding a legal status above mere legislation.

The full story of Khomeini's wartime fatwa against chemical weapons shows that when the "guardian jurist" of Iran's Islamic system issues a religious judgment against weapons of mass destruction as forbidden by Islam, it overrides all other political-military considerations. Khomeini's fatwa against chemical weapons prevented the manufacture and use of such weapons — even though it put Iranian forces at a major disadvantage in the war against Iraq and even though the IRGC was strongly in favor of using such weapons. It is difficult to imagine a tougher test of the power of the leader's Islamic jurisprudence over an issue.

Given the fundamental misunderstanding of the way in which the Islamic Republic has made policy on weapons of mass destruction, the episode of Khomeini's fatwa has obvious implications for the nuclear negotiations with Iran. Negotiators who are unaware of the real history of Iran's anti-nuclear fatwas will be prone to potentially costly miscalculations.