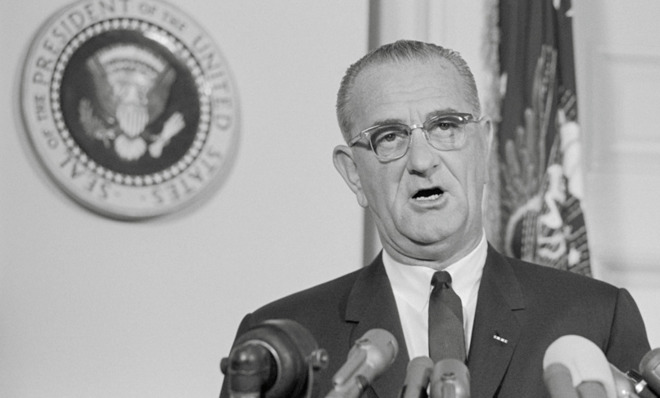

Why Lyndon B. Johnson is the worst modern president

Don't believe the hype

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The competition for worst president since the early 1930s is pretty fierce. But for my money, Lyndon B. Johnson comes in first, winning the contest of awfulness over George W. Bush by a hair.

The bloody debacle of the Vietnam War has a lot to do with this judgment (just as Iraq plays a big role in my negative assessment of Bush). According to a recent front-page story in the New York Times, the keepers of Johnson's legacy fear that I'm not alone. In an effort to rehabilitate his reputation, these Johnson defenders, who include members of his family, have begun an effort to direct attention away from the war and toward his achievements in domestic policy instead.

I'm afraid that doesn't solve the problem.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Yes, passage of the Civil Rights Act will always be a milestone in the history of race relations in the United States. But beyond that accomplishment, Johnson's record in domestic affairs suffered from the same defect as his foreign policy did: A reckless disregard for limits.

As I argued in a recent column about the "war on poverty," Johnson announced his wildly unrealistic goal of eliminating poverty prior to formulating any concrete ideas about how it might be achieved. He simply assumed that it could be done if we set our minds to it, so he declared the rhetorical war and left it to his advisers to craft policies that would win it. No surprise that the war was lost as a result. Indeed, one of the main legacies of the "war on poverty" was an increased cynicism about what the government can achieve.

The same dynamic prevailed in Johnson's case for the creation of a "Great Society," made in a speech delivered in Michigan on May 22, 1964. Living on the far side of Ronald Reagan's rhetorical attacks on big government, Bill Clinton's pragmatic triangulation, and Barack Obama's decision to reform health care using a proposal first floated by a right-wing think tank, Johnson's bizarrely inflated rhetoric cannot help but sound like the transcript from an alien political world.

Johnson starts by proposing that the U.S. move "not only toward the rich society and the powerful society, but upwards to the Great Society." This society "demands an end to poverty and racial injustice."

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

"But that," Johnson tells us, "is just the beginning."

The Great Society will be a place where "every child" finds knowledge to "enrich his mind and enlarge his talents." It will also be a place where "leisure is a welcome chance to build and reflect, not a feared cause of boredom and restlessness," and also where people move beyond "the needs of the body and the demands of commerce" to strive for "beauty" and "community."

People in the Great Society will "renew contact with nature," honor "creation for its own sake," and care more about the "quality of their goals than the quantity of their goods."

"But most of all," Johnson proclaims, "the Great Society is not a safe harbor, a resting place, a final objective, a finished work. It is a challenge constantly renewed, beckoning us toward a destiny where the meaning of our lives matches the marvelous products of our labor."

Referencing Aristotle, Johnson sums up his vision for the Great Society by committing it to combating "loneliness and boredom and indifference" so that citizens would be free "not only to live but to live the good life."

Really? Boredom?

The problem with this agenda isn't that Johnson proposed unworthy goals. It's that he proposed goals that were too worthy — and obviously, indisputably unattainable for many individuals, let alone for any conceivable government program. (An older liberal friend of mine claims to have thought at the time that in this speech Johnson came awfully close to sounding like Santa Claus.)

Johnson's approach was similar with the war in Vietnam, though with much greater and far more deadly consequences. The objective — military victory over the godless Commies in southeast Asia — was not implausible on its face, but it was enunciated without a clear plan for how it could be achieved. Johnson seemed to assume that all we needed was the will to make it happen.

When it comes to the social welfare programs that Johnson signed into law in order to prosecute the war on poverty and realize the Great Society, they were a decidedly mixed bag. Some, like Medicare, have proven popular and enduring. Others, like the anti-poverty programs wrapped up with the Office of Economic Opportunity, were far less effective, and ended up being dismantled during the conservative resurgence they helped to inspire.

In every case, the policies would have been better served by a more modest rhetorical justification.

Johnson's presidency went down in flames because it could never live up to his own irresponsibly exalted standards. Despite what his apologists may think and hope, the damage to his reputation can't be erased by distracting attention from Vietnam, which was only one aspect of a multifaceted failure.

Damon Linker is a senior correspondent at TheWeek.com. He is also a former contributing editor at The New Republic and the author of The Theocons and The Religious Test.

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred