What's the point of baby talk?

The science is divided over the efficacy of motherese

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Do you know what I'd like to know? Do you? Dooo you? Yes! Yeeeesss! Yes, you dooo! Don't you?

Well, if you don't, I'll tell you. What I'd like to know is: What's the point of baby talk?

This is a bit of a disingenuous question, because I'm going to give you some possible answers. But I'm not entirely sure which, if any, of them is right. Linguists don't agree on this. Seriously: You can take courses from different professors who will tell you directly contradictory things with equal certainty.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

You may not know the term motherese, but I'm sure you'll recognize what it is when I tell you it's that way many people speak to infants. (Also to dogs, sometimes to cats, sometimes even to senior citizens.) Linguists have several terms for this. The classical term is motherese, though it's fallen out of fashion a bit in recent years. Caregiver speech or caregiverese are sometimes seen, and the more technical-sounding options are infant-directed speech and child-directed speech (there is also pet-directed speech, senior-directed speech, etc., to allow for differences).

It turns out that motherese is fairly similar in most languages: Shorter phrases, simpler grammar, different versions of words, repetitions, slower speech, higher pitch, very exaggerated pitch contours (just think of someone saying to a baby, "Who's that? Say hiiii!"), and more exaggerated vowel contrasts (wider-open "ah"s, tighter "ee"s, and so on).

The idea, according to some, is that all this is important to help babies learn language.

But is motherese important in child language learning, really?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Well, here's the thing: In some societies, they not only refrain from using baby talk, but also refuse to speak to them at all. Linguists who hold no truck with motherese will quickly point to work by Elinor Ochs of UCLA in which she contrasted the helpful, encouraging, accommodating, motherese-using approach common in America with that of societies such as Western Samoa, where children who can't talk aren't spoken to directly.

Furthermore, when Samoan children are learning language, if they say something unclear, the parent doesn't guess what it is and help them along — he or she just tells the child it can't be understood. And how does this affect Samoan language learning? Well, obviously the children learn language. After all, the parents were once infants, too.

So does that mean motherese has no effect on children's language learning? There is some evidence that it may help.

First of all, babies — especially ones half a year old or less — seem to prefer motherese. This isn't really surprising; babies also like bright colors. Bigger contrasts seem to appeal to them more: Big rises and falls in pitch, mouths open wide or closed tight when speaking, etc.

Secondly, some aspects of motherese do seem to correlate with better language learning in infants. Studies have found that infants appear to detect such things as syllable and phrase boundaries better when hearing motherese, and that infants spoken to with motherese appear to be better at identifying differences between consonants.

A common hypothesis is that better ability to discriminate sounds leads to better ability to learn words and grammar. Some studies have indicated that how mothers talk to infants before they're old enough to speak can have an effect on the children's language abilities a year or so later.

However, the studies that show positive effects only focus on specific areas. They don't show overwhelming effects, while some studies have not found any meaningful effects at all.

There are also factors that are very hard to filter out. For starters, we have to remember that most of the speech an infant hears is normal speech, not motherese, because most of the speech it hears is not directed towards it. And not all the speech directed to the infant will be motherese, either — it's unlikely that every person who speaks to the baby will use motherese. Finally, women who use motherese will hopefully speak differently when speaking to adults, and the babies will overhear that, too.

Motherese isn't likely to help children learn much about grammar directly, either, considering it's so often grammatically incomplete or plain old wrong.

So if motherese has positive effects, they are not enough to make the difference between a child genius and a semiliterate Neanderthal, and may not even be enough to make the difference between a B+ and an A– in English class years later.

And that's if it has positive effects. The evidence is inconclusive enough so far that it will continue to make developmental linguists' careers for decades to come. But I know two things that shape my opinion on whether to use motherese:

First, two of the most highly literate, grammatically acute people I know, with the largest vocabularies, grew up with linguist parents who never used motherese with them.

Second, motherese drives me nuts. Yesss! Yes it does! Oh yeeeeeesssss! Doesn't it drive you nuts too?! Doesn't it? Doesn't it?!

I mean, especially when people use it with their dogs. But also when they use it with babies. So I can't stop you from using it, but I wish I could. After all, what we do know is that it's not essential for child language development, and probably doesn't make all that much difference.

James Harbeck is a professional word taster and sentence sommelier (an editor trained in linguistics). He is the author of the blog Sesquiotica and the book Songs of Love and Grammar.

-

The ‘ravenous’ demand for Cornish minerals

The ‘ravenous’ demand for Cornish mineralsUnder the Radar Growing need for critical minerals to power tech has intensified ‘appetite’ for lithium, which could be a ‘huge boon’ for local economy

-

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?IN THE SPOTLIGHT As the president muses about polling place deployments and a centralized electoral system aimed at one-party control, lawmakers are taking this administration at its word

-

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

In the future, will the English language be full of accented characters?

In the future, will the English language be full of accented characters?The Explainer They may look funny, but they're probably here to stay

-

10 signature foods with borrowed names

10 signature foods with borrowed namesThe Explainer Tempura, tajine, tzatziki, and other dishes whose names aren't from the cultures that made them famous

-

There's a perfect German word for America's perpetually enraged culture

There's a perfect German word for America's perpetually enraged cultureThe Explainer We've become addicted to conflict, and it's only getting worse

-

The death of sacred speech

The death of sacred speechThe Explainer Sacred words and moral terms are vanishing in the English-speaking world. Here’s why it matters.

-

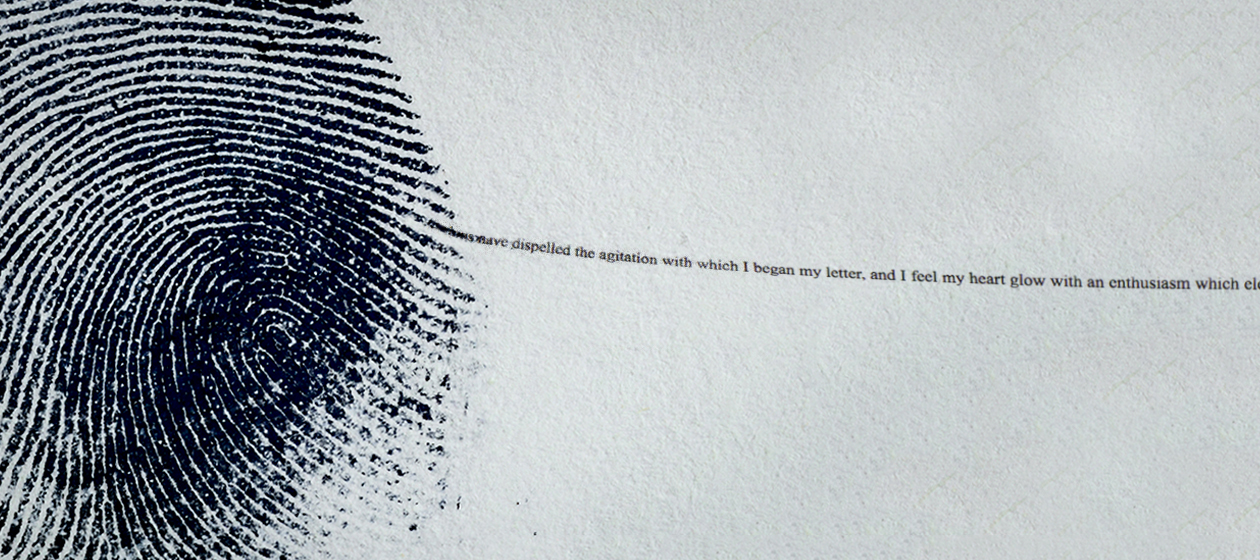

The delicate art of using linguistics to identify an anonymous author

The delicate art of using linguistics to identify an anonymous authorThe Explainer The words we choose — and how we use them — can be powerful clues

-

Dashes and hyphens: A comprehensive guide

Dashes and hyphens: A comprehensive guideThe Explainer Everything you wanted to know about dashes but were afraid to ask

-

A brief history of Canadian-American relations

A brief history of Canadian-American relationsThe Explainer President Trump has opened a rift with one of America's closest allies. But things have been worse.

-

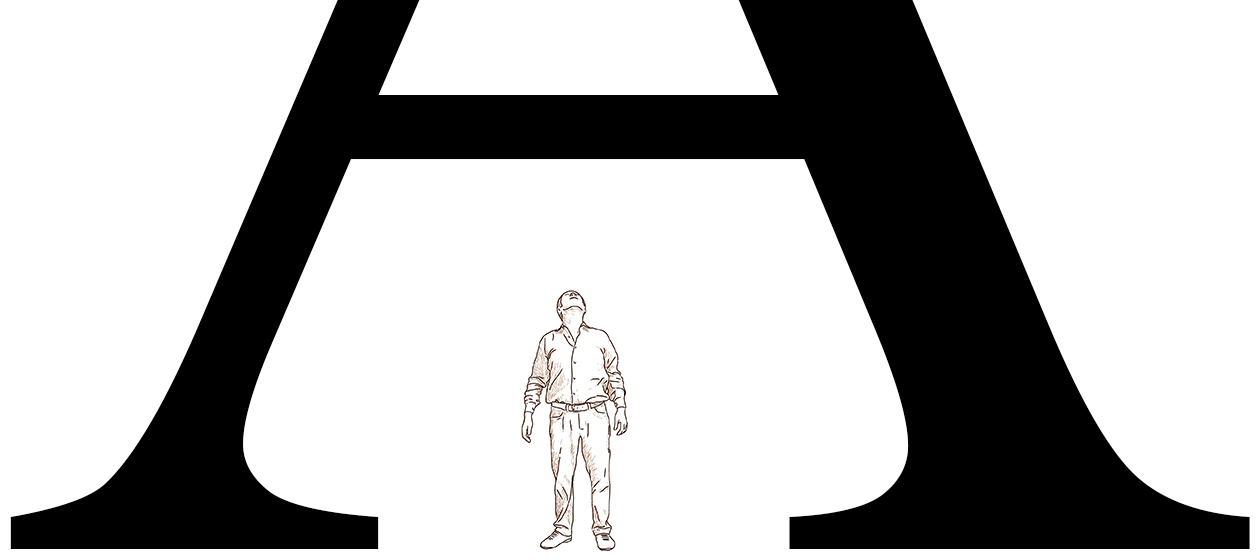

The new rules of CaPiTaLiZaTiOn

The new rules of CaPiTaLiZaTiOnThe Explainer The rules for capitalizing letters are totally arbitrary. So I wrote new rules.