Health & Science

Sunscreen as a youth serum; Tweaking mosquitoes’ taste; A Mars travel advisory; The origins of French wine

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Sunscreen as a youth serum

Sunscreen doesn’t just protect against skin cancer. People who apply sunscreen every day have fewer wrinkles, and their skin is visibly smoother and more elastic than the skin of those who don’t, a new study has found. Australian researchers recruited 900 mostly fair-skinned volunteers between the ages of 25 and 55, and asked half of them to religiously apply SPF 15 to their head, neck, arms, and hands every morning for four and a half years. When the researchers compared silicone casts of the subjects’ skin taken at the beginning and the end of the study, they found that the skin of those who had followed the sunscreen regimen showed 24 percent fewer signs of aging than those who had not. Middle-aged participants and those with moderate skin damage reaped the same benefits from applying sunscreen daily as did those who started out with younger-looking skin. Ultraviolet rays damage collagen, which gives skin its plump, youthful appearance, so it makes sense that blocking those rays would slow down the skin’s aging process. “As dermatologists, we have been saying for years and years, use SPF every day all year round,” New York dermatologist Doris Day tells Time.com. “If you don’t need a flashlight to see outside, you need protection.”

Tweaking mosquitoes’ taste

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Scientists have figured out a way to suppress the preference many mosquito species have for biting humans above all other animals. The blood-sucking insects probably evolved that taste because people tend to live in groups and near water, where mosquitoes lay their eggs. “They love our beautiful body odor, they love the carbon dioxide we exhale, and they love our body heat,” Rockefeller University neurobiologist Leslie Vosshall tells Nature.com. Vosshall and her colleagues have now genetically engineered one human-loving mosquito species so that it lacks an odor receptor, making the insects unable to tell the difference between people and other animals. “By disrupting a single gene, we can fundamentally confuse the mosquito from its task of seeking humans,’’ Vosshall says. The research could lead to new and better repellents.

A Mars travel advisory

The idea of sending human beings to Mars has always faced enormous technical challenges—but it just got a lot more challenging. Newly analyzed data from the Curiosity rover shows that on the trip to the Red Planet, travelers would be bombarded every five or six days with as much radiation as they’d get from a full-body CT scan. Despite being tucked under a protective shield during its 253-day trip to Mars last year, the spacecraft’s radiation detector was inundated with high-energy protons from the sun, as well as galactic cosmic rays for which there is no effective shield. Mars travelers would see their cancer risk increase by about 3 percent if they made a round trip, experts estimate, and they could also face damaged eyesight and cognitive impairments from radiation. But proponents of Mars travel aren’t deterred by the findings. A private mission for a Mars flyby in 2018 is seeking a 50-ish married couple, who would have fewer years left to develop radiation-caused cancer, while NASA hopes to devise faster propulsion and better radiation shields before sending humans to Mars in the 2030s. “Radiation is not a showstopper,’’ Robert Zubrin, president of the Mars Society, tells NPR.org. “It’s not something that the FDA would recommend that everyone do. But we’re talking about a mission to Mars here.’’

The origins of French wine

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

The French may consider themselves the world’s greatest wine experts today, but new archaeological evidence suggests they first learned how to make it from residents of what is now Italy, says Scientific American. Researchers have long known that winemaking originated in the Middle East around 8,000 years ago, but they weren’t sure how it spread westward. In a town on France’s Mediterranean coast, archaeologists recently found old pottery jars, or amphoras, that had been shipped from central Italy in around 500 B.C. Sophisticated testing found traces of wine in the amphoras, indicating that the French had first “imported’’ wine from the Etruscan civilization in Italy. Near the amphoras researchers unearthed a limestone press, which analysis showed had been used to crush grapes and make wine—a few decades after the amphoras arrived. Researchers now theorize that the French elite developed a taste for imported Italian wine and almost immediately made it their alcoholic beverage of choice, instead of their native drinks, “which were likely beers, meads, and mixed fermented beverages,” says University of Pennsylvania archaeologist Patrick McGovern. Demand became so great that soon the French began producing their own vintages, probably with instructions from the Italians and grapevines transplanted from their vineyards.

-

American empire: a history of US imperial expansion

American empire: a history of US imperial expansionDonald Trump’s 21st century take on the Monroe Doctrine harks back to an earlier era of US interference in Latin America

-

Elon Musk’s starry mega-merger

Elon Musk’s starry mega-mergerTalking Point SpaceX founder is promising investors a rocket trip to the future – and a sprawling conglomerate to boot

-

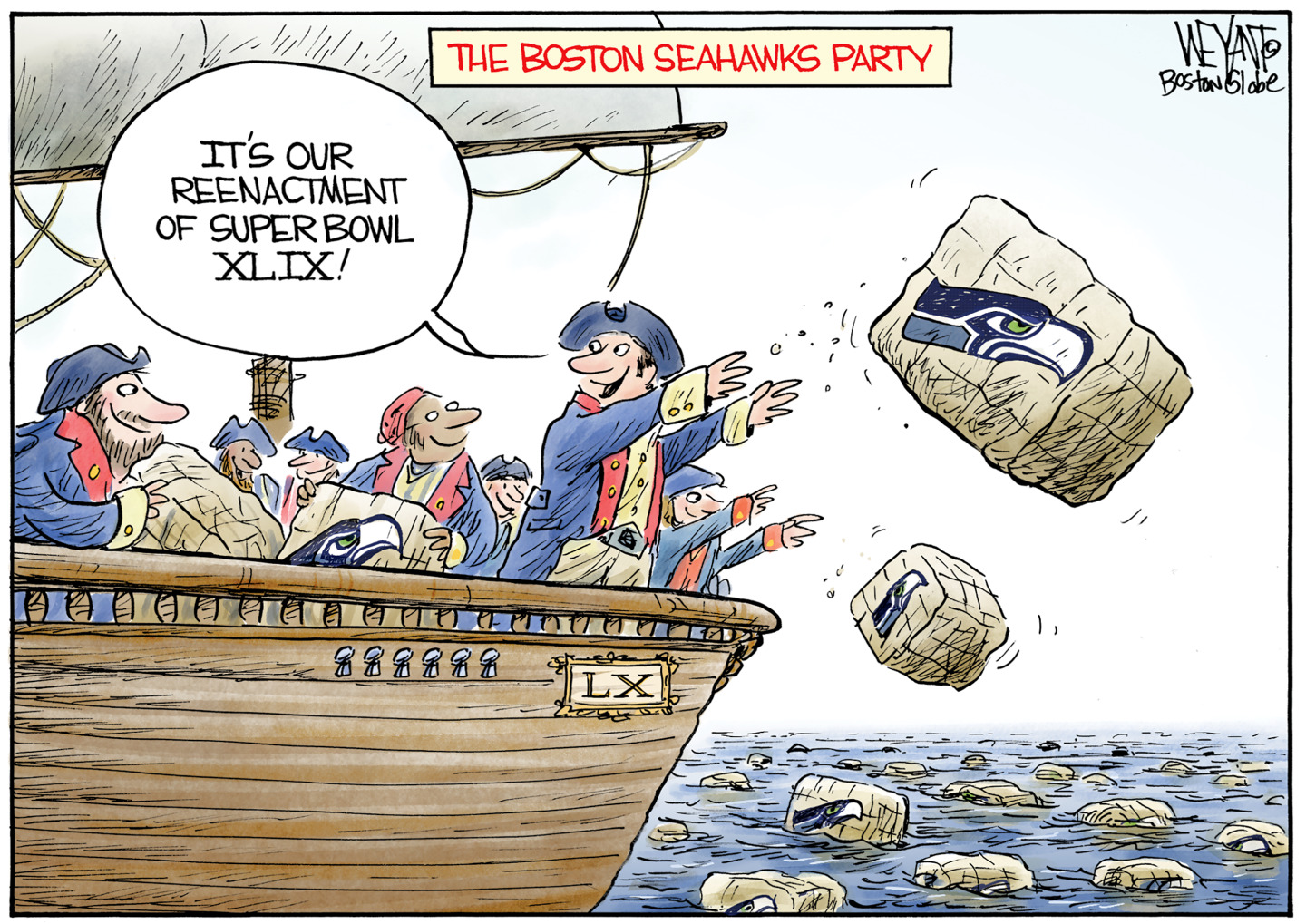

5 superbly funny cartoons about the Superbowl

5 superbly funny cartoons about the SuperbowlCartoons Artists take on historical reenactment, biased bowls, and more

-

5 recent breakthroughs in biology

5 recent breakthroughs in biologyIn depth From ancient bacteria, to modern cures, to future research

-

Bacteria can turn plastic waste into a painkiller

Bacteria can turn plastic waste into a painkillerUnder the radar The process could be a solution to plastic pollution

-

Scientists want to regrow human limbs. Salamanders could lead the way.

Scientists want to regrow human limbs. Salamanders could lead the way.Under the radar Humans may already have the genetic mechanism necessary

-

Is the world losing scientific innovation?

Is the world losing scientific innovation?Today's big question New research seems to be less exciting

-

Breakthrough gene-editing treatment saves baby

Breakthrough gene-editing treatment saves babyspeed read KJ Muldoon was healed from a rare genetic condition

-

Humans heal much slower than other mammals

Humans heal much slower than other mammalsSpeed Read Slower healing may have been an evolutionary trade-off when we shed fur for sweat glands

-

Scientists map miles of wiring in mouse brain

Scientists map miles of wiring in mouse brainSpeed Read Researchers have created the 'largest and most detailed wiring diagram of a mammalian brain to date,' said Nature

-

Scientists genetically revive extinct 'dire wolves'

Scientists genetically revive extinct 'dire wolves'Speed Read A 'de-extinction' company has revived the species made popular by HBO's 'Game of Thrones'