Why poverty is growing faster in the suburbs than in the city

Urban areas are no longer the country's main centers of poverty

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

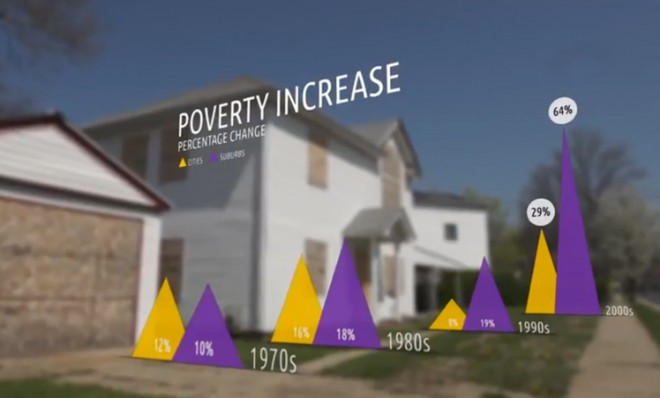

Poverty is exploding in what might seem the least likely of places: America's suburbs. According to a new study by the Brookings Institution, the number of poor people living in suburban areas jumped by 67 percent from 2000 to 2011 — more than twice the growth rate in cities.

Today, 16.4 million poor people live in the suburbs, more than in either urban or rural areas. What happened in the last decade to cause such a drastic rise in suburban poverty?

1. Changing demographics

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Suburbs as a whole increased in population by 14 percent during that period, compared to only 4.5 percent in cities. With that population boom came an increase of construction, manufacturing, and retail jobs, all of which were severely affected by the Great Recession.

"There were a lot of suburbs that were at the forefront of the recession, places that built too much housing," Alan Berube, co-author of the study and deputy director of the Metropolitan Policy Program, told The Dallas Morning News. "And when prices fell and people couldn’t buy because of the mortgage crisis, employment and the economy in those places dried up quickly."

In fact, nine of the 10 highest suburban poverty rates are in California, Texas, Florida, and New Mexico — all areas with pre-recession housing booms that attracted lots of new residents looking for cheap homes and construction jobs.

2. Strong suburban growth pre-downturn

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

The rise in poverty wasn't just limited to areas with high foreclosure rates. The study's other author, Elizabeth Kneebone, noted that some suburban areas around wealthy, well-educated cities like Portland, Ore., Madison, Wis., and Minneapolis, Minn. were victims of their own success.

"These regions were growing, particularly before the downturn," Kneebone told The Minneapolis Star Tribune. "A diverse population responded to that, and then when the economy turned down, a lot of people either were without work or finding work that pays less."

3. Gentrification

Gentrification in places like New York City might also have played a role.

"It seems like as the city prospered and got more expensive over the 2000s, poverty crept up in a lot of the region’s older suburban communities," Berube told The New York Times.

He added that the change was not necessarily spurred by poor city-dwellers moving to the suburbs, but rather suburban areas attracting new low-income residents that in the past would have settled in the increasingly pricey New York City boroughs of Brooklyn and the Bronx.

4. More versatile housing vouchers

Another reason for the shift, according to the study, is the increased mobility of housing vouchers. Previously, they were restricted by area. When that changed, poor families in search of safe streets and good schools used the vouchers to move out of the city and into the suburbs. By 2010, about half of the residents using housing vouchers were living in the suburbs.

The study, explored in greater depth in the book Confronting Suburban Poverty in America, raises concerns that the rise in suburban poverty has overwhelmed areas unaccustomed to providing services to people with low incomes. Ever since President Lyndon Johnson announced his "War on Poverty" in 1964, most anti-poverty resources have been focused on urban centers.

Now suburban families living in poverty have to overcome their challenges while having limited access to public transportation, job counselors, and health services. Federal and state governments, which previously directed their resources towards a few dense clusters, have to figure out how to help a more dispersed population of poor people throughout the country.

"This isn't about shifting resources away from the cities," Kneebone told The Los Angeles Times. "But it underscores the need to think differently."

Keith Wagstaff is a staff writer at TheWeek.com covering politics and current events. He has previously written for such publications as TIME, Details, VICE, and the Village Voice.