Health & Science

The mammal that inherited the Earth; A Great Lakes crisis; Reducing the risk of autism; Moose dying in droves

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The mammal that inherited the Earth

The common ancestor of almost all mammals on Earth today—including human beings—was a furry, long-tailed, rat-sized creature that emerged after the extinction of the dinosaurs. In a six-year study that collated vast amounts of data on anatomical traits throughout the mammalian family tree, researchers discovered that all modern mammals that nourish their unborn young through a placenta—including bats, cats, elephants, whales, and humans—evolved from a single insect-eating, tree-climbing species called Protungulatum donnae. “This is a landmark piece of work,” paleontologist Stephen Brusatte of the University of Edinburgh tells New Scientist. Previous research has suggested that several lines of placental mammals co-existed with the dinosaurs, but the new study backs the hypothesis that they emerged only after an asteroid 66 million years ago killed off most of the massive reptiles, paving the way for a mammalian takeover beginning 200,000 to 400,000 years later. The new timeline suggests that the first placental mammal is 36 million years younger than previously thought, says John Gatesy, an evolutionary biologist at the University of California, Riverside—a finding that “will surely be controversial” because it clashes with dating derived from genetic evidence.

A Great Lakes crisis

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Lake Michigan and Lake Huron have dropped to their lowest levels on record, threatening their shipping and fishing industries. A new report by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers found that the two lakes are 29 inches below their long-term average—lower than they’ve been since record-keeping began, in 1918—and that more than half of the drop occurred since January 2012. The other Great Lakes—Superior, Erie, and Ontario—are also much shallower than usual. “We’re in an extreme situation,” Detroit-based Corps hydrologist Keith Kompoltowicz tells the Associated Press. The Great Lakes hold 84 percent of the freshwater in North America and are major shipping routes. Lower water levels damage coastal wetlands and restrict the amount of cargo that ships can carry. Researchers partly blame climate change: Years of record-high temperatures have accelerated evaporation from the lakes at the same time rainfall has lessened. Dredging to deepen the navigational channel of the St. Clair River, into which Michigan and Huron empty, may have also caused as much as a 16-inch drop in the lakes’ water levels over the years.

Reducing the risk of autism

Scientists still can’t explain why one in 88 children in the U.S. has autism—a number that’s risen sharply over the past decade. But now a new study suggests that pregnant women can significantly reduce their risk of having an autistic child by taking folic acid supplements. Researchers in Norway recorded the diets of more than 85,000 pregnant women who gave birth between 2002 and 2008. They discovered that women who took folic acid supplements beginning four weeks before conception and continuing through the first eight weeks of pregnancy were 40 percent less likely to have a severely autistic child than those who didn’t. “That’s a huge effect,’’ Columbia University epidemiologist Ian Lipkin tells NPR.org. “The notion that a very simple, nontoxic food supplement could reduce your risk is profound.” Leafy vegetables, beans, and most whole grains contain folic acid, but eating a healthy diet doesn’t provide sufficient folic acid to provide the protective benefits, Lipkin says. “You have to take the vitamins.”

Moose dying in droves

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Minnesota biologists are scrambling to figure out what is causing an epidemic of moose deaths in the state. A recent estimate shows that the animals’ numbers have declined by 52 percent over the past two years, leaving only about 2,760 moose left. “The adult moose are literally tipping over dead,” Steve Merchant of the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources tells The Wall Street Journal. Researchers believe that warming temperatures caused by climate change may be causing stress among the cold-weather-dependent animals, causing them to take shelter instead of foraging for food. Such behavior, says National Wildlife Federation biologist Doug Inkley, would make them “more vulnerable to disease and parasites.” Warming temperatures have also caused a population explosion of northern ticks, which could be spreading more disease among moose or simply sucking so much blood from them that they become anemic. Declines in moose numbers have also been reported in some Rocky Mountain states, but last year’s moose census in Maine, which has the largest moose population in the U.S., showed a sharp increase. Wildlife officials have canceled Minnesota’s annual moose hunt and put GPS collars on 100 moose in the hopes of figuring out what’s killing them.

-

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?IN THE SPOTLIGHT As the president muses about polling place deployments and a centralized electoral system aimed at one-party control, lawmakers are taking this administration at its word

-

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

Earth is rapidly approaching a ‘hothouse’ trajectory of warming

Earth is rapidly approaching a ‘hothouse’ trajectory of warmingThe explainer It may become impossible to fix

-

5 recent breakthroughs in biology

5 recent breakthroughs in biologyIn depth From ancient bacteria, to modern cures, to future research

-

Bacteria can turn plastic waste into a painkiller

Bacteria can turn plastic waste into a painkillerUnder the radar The process could be a solution to plastic pollution

-

Scientists want to regrow human limbs. Salamanders could lead the way.

Scientists want to regrow human limbs. Salamanders could lead the way.Under the radar Humans may already have the genetic mechanism necessary

-

Is the world losing scientific innovation?

Is the world losing scientific innovation?Today's big question New research seems to be less exciting

-

Breakthrough gene-editing treatment saves baby

Breakthrough gene-editing treatment saves babyspeed read KJ Muldoon was healed from a rare genetic condition

-

Humans heal much slower than other mammals

Humans heal much slower than other mammalsSpeed Read Slower healing may have been an evolutionary trade-off when we shed fur for sweat glands

-

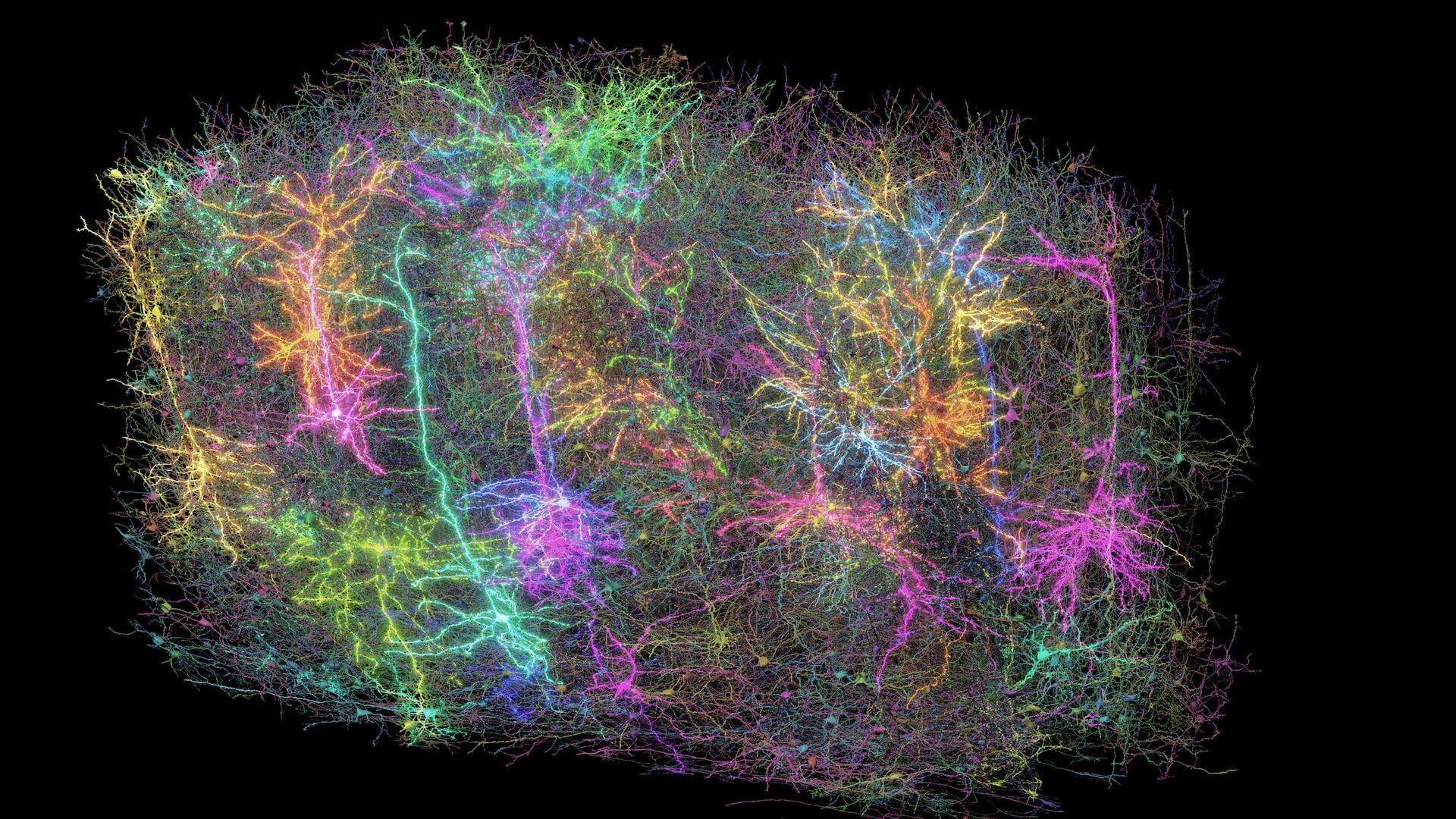

Scientists map miles of wiring in mouse brain

Scientists map miles of wiring in mouse brainSpeed Read Researchers have created the 'largest and most detailed wiring diagram of a mammalian brain to date,' said Nature

-

Scientists genetically revive extinct 'dire wolves'

Scientists genetically revive extinct 'dire wolves'Speed Read A 'de-extinction' company has revived the species made popular by HBO's 'Game of Thrones'