Health & Science

Why it’s never too late to quit smoking; Incredible insect astronomers; A scan for concussion damage; Your fatal feline

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Why it’s never too late to quit smoking

Everyone knows smoking can shorten your life—but a new study spells it out in years. Lifelong smokers die an average of 10 years younger than nonsmokers do, say researchers who analyzed data on 220,000 American men and women over decades. But the study found good news, too: Smokers who manage to quit by age 35 can add that decade back onto their life expectancy. Even kicking the habit before age 60 is good for as many as six more years of life. That’s “a very encouraging message,” especially for middle-aged smokers, study author Prabhat Jha of St. Michael’s Hospital in Toronto tells NPR.org. “They might think, ‘Oh, it’s too late. There’s no point for me to quit because the damage is done.’ But that’s not true.’’ While smoking rates in the U.S. have dramatically declined from 40 percent of the population to less than 20 percent, the study found, women’s risk of dying from lung cancer has actually increased, largely because those who do smoke are starting younger and lighting up more often. The research data sends a very clear message, says Dr. Tim McAfee of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Don’t start smoking, but if you already have, the benefits of quitting are enormous. “The notion that you could add 10 years to your life by something as straightforward as quitting smoking is just mind-boggling,’’ he says.

Incredible insect astronomers

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Scientists have long known that birds and seals navigate by the stars. Now they’ve discovered that even the lowly dung beetle uses the Milky Way as a compass. “This is a complicated navigational feat—it’s quite impressive for an animal that size,” biologist Eric Warrant of the University of Lund, in Sweden, tells NationalGeographic.com. Males among the inch-long beetles compete for mates by finding animal dung, sculpting a portion of it into a ball, and quickly rolling it away from the heap before another beetle can steal it. The dung ball then serves as food and as an incubator in which a female he has courted will lay a single egg. Researchers noticed that the beetles appeared adept at navigating away from a dung pile under clear skies, but on overcast nights they rolled in circles. So researchers took them to a planetarium. There, when the streak of the Milky Way was visible, the beetles’ path was direct and unerring. Warrant believes further research could establish stellar navigation as a widespread skill among insects. “Migrating moths might also be able to do it,” he says.

A scan for concussion damage

Evidence is mounting that concussions put professional and even high school athletes at risk of chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE), a degenerative brain disease that can lead to severe depression and dementia. Until recently, however, doctors could only spot signs of CTE postmortem in autopsies, like the one that found the disease in former NFL player Junior Seau, who killed himself last year. Now, for the first time, researchers using positron emission tomography scans have diagnosed CTE in living patients, raising hopes that doctors can intervene earlier “rather than try to repair damage once it becomes extensive,” Gary Small, a psychiatry professor at the Semel Institute, tells The New York Times. He and his colleagues injected five retired pro football players with a special chemical marker that attaches to tau proteins, which are linked to the disorder. When they scanned the ex-players’ brains, all five showed significantly higher levels of tau than a control group did. If the testing technique can be fully developed, the implication of being able to detect damage in the brains of living athletes “could be enormous,” says study coauthor Julian Bailes. “What if these guys could walk away at the right time?”

Your fatal feline

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Domestic cats are far deadlier than anyone imagined. A new study estimates that felines massacre 2.4 billion birds and 12.3 billion mammals every year in the U.S.—two to four times the number scientists expected. “We were absolutely stunned by the results,” study author Peter Marra of the Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute tells The New York Times. The study makes cats out to be a greater threat to wildlife than any other human-linked source, including pesticides and collisions with cars, windows, and windmills. The domestic cat is a non-native species, and it preys not just on vermin like rats, but also on native shrews, squirrels, chipmunks, and voles. Researchers say that stray cats account for most of the damage. But pets that are let outside to roam do up to 30 percent of the killing. An average roaming house cat, researchers said, kills up to 18 birds and 21 mammals annually.

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?Today’s Big Question Democrats want to rein in ICE’s immigration crackdown

-

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

5 recent breakthroughs in biology

5 recent breakthroughs in biologyIn depth From ancient bacteria, to modern cures, to future research

-

Bacteria can turn plastic waste into a painkiller

Bacteria can turn plastic waste into a painkillerUnder the radar The process could be a solution to plastic pollution

-

Scientists want to regrow human limbs. Salamanders could lead the way.

Scientists want to regrow human limbs. Salamanders could lead the way.Under the radar Humans may already have the genetic mechanism necessary

-

Is the world losing scientific innovation?

Is the world losing scientific innovation?Today's big question New research seems to be less exciting

-

Breakthrough gene-editing treatment saves baby

Breakthrough gene-editing treatment saves babyspeed read KJ Muldoon was healed from a rare genetic condition

-

Humans heal much slower than other mammals

Humans heal much slower than other mammalsSpeed Read Slower healing may have been an evolutionary trade-off when we shed fur for sweat glands

-

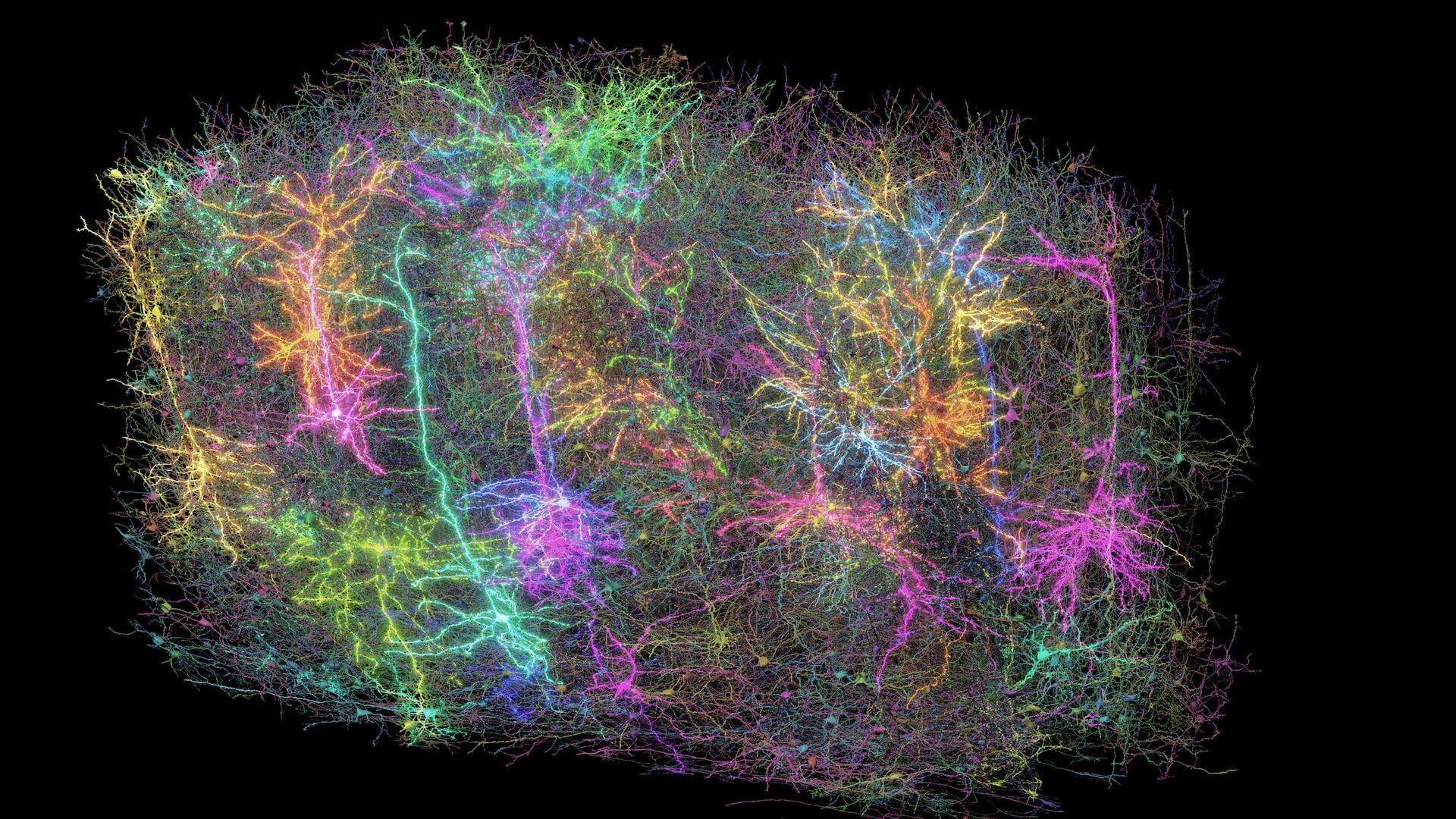

Scientists map miles of wiring in mouse brain

Scientists map miles of wiring in mouse brainSpeed Read Researchers have created the 'largest and most detailed wiring diagram of a mammalian brain to date,' said Nature

-

Scientists genetically revive extinct 'dire wolves'

Scientists genetically revive extinct 'dire wolves'Speed Read A 'de-extinction' company has revived the species made popular by HBO's 'Game of Thrones'